"I missed normal literary communication so much."

Lina Vasylivna, thank you for finding time for us.

How could I not find time for you? I rarely find time for anyone. But, you know, Serhiy, I missed normal literary communication so much. And I must tell you that the last 30 years have been marked by some kind of hostility between people, some kind of protagonists, some people who began to be called cult writers.

Well, yes, the last 30 years have been very strange discussions.

I even came up with this quick quatrain:

Thirty years have passed — not few,

But what was built, what did they do?

“Ukrainian lit,” they proudly claim —

Bravo, you bastards — what a shame.

You understand, you have nothing to do with this. And a few more writers and poets are gone.

But the worst thing is that several poets have died. I just can't bear it. Ilya's son died. Shovkoshytnyy's son died, Chernilevskyy's son died (Taras Ilya — poet, son of poets Valentina Otroshchenko and Valeriy Ilya. He died on the front in 2024. Heorhiy Shovkoshytnyy (1983–2024) — poet, son of poet Volodymyr Shovkoshytnyy. He died in 2024 near Malaya Tokmachka in Zaporizhzhya. Ilya Chernilevskyy (1991–2022) — poet, son of poet Stanislav Chernilevskyy. He died in 2022 near Kamyanka in Donetsk Region — Ed.)

How can this be? A young man writes: "I am not yet killed, I am still praying." I cannot bear these lines.

I wanted to ask you about this. These years of terrible, dramatic war, which began in 2014: you are very sensitive to changes in sound. How does Ukraine sound to you today? How do you hear it?

Probably for the first time in a dignified way. There are still various people who interfere with Ukraine's progress. There are bad people who do not love Ukraine. Sometimes even in the diaspora there are people who do not represent our nation well... It's so bitter.

Once, when I was being "tested for the purity of my nation," one man shouted, "Do you like borscht?!" How can I say whether I like it or not, you understand? So, when they blurt out things like that, Ukraine loses.

It's not just Ukrainians who are to blame. It's the constant narratives from Russia. It has done everything to humiliate this nation. And it's so confusing for us. I need to find some real reason. Recently, we've started saying, "We Ukrainians built their empire. So we'll destroy it."

That's where it [empire] came from, yes.

And is that something good that we gave them?

And is that really true? How much of an imperial idea is inherent in us, Ukrainians?

It's terribly complicated. I'm currently finishing a book about it. Did you know that our priest Feofan Prokopovich gave Peter I ideas that we are now suffocating under (Feofan Prokopovich (1677–1733) was a Ukrainian theologian and rector of the Kyiv Academy. He was the author of the concept of transforming Moscovia into an empire in the spirit of enlightened absolutism with the subordination of the church to the "autocrat" — Ed.).

And you're talking about a book of prose, right?

Yes. And Bezborodko? (Oleksandr Bezborodko (1747–1799) was a statesman of the Russian Empire from a Ukrainian noble family in Hlukhiv, Sumy Region. — Ed.) He was indeed very powerful, ruling both foreign and domestic policy. Bezborodko, who was initially a clerk in Hlukhiv. He was brought [to Russia] as a smart guy because there was a lack of personnel there.

A lack of brains.

A lack of brains. And Catherine grabbed them, you understand. And our people are very intelligent. And there are really a lot of them, these ministers, all of them... And we need to understand why they... You see, somewhere in Malanyuk it is written that a slave cried inside him. I know that those who went into the Russian nobility did not cry. They did not know what they were doing.

I listen to you and understand that for you, history is not just a set of historical facts, you try to compare it all and connect it with the present. You have two great ones, actually...

"Euterpe scolded Clio for not letting me have a bit on the side. But I had and still have, because I'm friends with both of them."(Euterpe is the muse of lyric poetry and music, Clio is the muse of history — Ed.)

Your two great novels in verse, Berestechko and Marusya Churai, are, in fact...

And Scythian Odyssey too... (Berestechko is a historical novel in verse by Lina Kostenko about the greatest battle of the Khmelnytsky Uprising in 1651. The battle ended with the Treaty of Bila Tserkva, which limited the Cossack territory and returned the peasants to Polish serfdom. Marusya Churai is a historical novel in verse by Lina Kostenko about the legendary Ukrainian singer of the 17th century, during the Khmelnytsky Uprising. The Scythian Odyssey is a ballad poem by Lina Kostenko about the Greek and Scythian worlds of the Black Sea region — Ed.).

"There are no ‘khokhly’. There is a nation, a real nation."

I wanted to ask about Berestechko and Marusya Churai in the context of war. In both cases, you have war, and in one way or another, Ukrainians are fighting. You are a poet who has written two epic works about war — how do you think war can characterise a people? How does the current war characterise Ukrainians?

Listen, we are heroic people. This is how a nation of heroes emerges, this is how a nation emerges from the population. Somewhere it is written: the boys grew and grew. But now the people are meeting them in the villages on their knees. So many have died. But you know, to be honest, I think that there is no people more worthy than Ukrainians right now. Because to withstand a war with a country like Russia is hard, you understand?

Again, forgive me for quoting myself, but it is easier for me to speak in verse, you can understand that, than in prose. I laugh: when I walk down the corridor — we have a long corridor here — I always write poems. I go to the kitchen to drink tea and say, Oksana (Lina Vasylivna's daughter Oksana Pakhlovska — Ed.), be quiet, I'm going to write something down. So, somewhere in my corridor, I wrote that "Russia, a power, fierce and proud, would crush the world, both near and loud. It kneaded fascist dough with hate, but knows not what it chose to bake." You see, "fascist dough" is scary. They are still looking for Bandera here. When they see our heroic boys near Chonhar, they say, "Ah, it's the khokhly (a derogatory Russian term for Ukrainians — Ed.)!" There are no ‘khokhly’. There is a nation, a real nation. And in Europe, I think, they now feel this. To endure a war like the Ukrainians have and not give up — I think many Europeans simply don't understand this.

You see, they created the European Union, signed an agreement that there would be no more war... In the 19th century, Alexander I created the Holy Alliance, promising "never again." So we, the "sovereign emperors," "shook hands" and went our separate ways. And what happened? The Holy Alliance fell apart. The League of Nations too. Now look at the state of the UN. Adopting two resolutions at the same time...(On 27 February 2025, the United States proposed its own draft UN resolution on the occasion of the third anniversary of the invasion. The theses of the resolution contradicted the vision of Ukraine and other European countries — Ed.) It's like loving one and the other, what is that? It's terrible cowardice. And Ukrainians are fighting.

I had already begun to suspect that we simply underestimate ourselves. They imposed this inferiority complex on us. I never understood what inferiority was. They said that Ukrainians were on their knees. I wrote somewhere that in order to get up from your knees, you first have to get down on them. They turned the nation into something unknown.

And since they are all over Europe and America, they are everywhere, you understand? My Oksana is the head of the Ukrainian Studies Department at the University of Rome (Oksana Pakhlovska, daughter of Lina Kostenko, professor at the University of Rome La Sapienza — Ed.). She has been working there for about 20 years. Since the 90s. Listen, what was it like at first? These Russian departments are terrible.

Well, they are actually political representations of Russia. There is no mention of science there.

Absolutely. You know, they were in charge everywhere.

They are, in fact, the heirs of a great empire, the heirs of their culture, the heirs of victory over fascism, and somewhere there — the Baltic peoples, the Caucasian peoples, Ukraine — somewhere there.

It [Ukraine] fought and fought. Listen, now even Russianists treat Ukraine with respect and send me their regards.

They have discovered for themselves that Ukrainian studies exist, that Ukrainian culture exists.

Where does the idea of great Russian culture come from? They came to St. Petersburg, and it was dazzling. Russian culture: Quarenghi built this, Rastrelli built that, Montferrand built the other. (Giacomo Quarenghi, Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli — Italian architects, Auguste Ricard Montferrand — French architect. Architects in the Russian Empire in the 18th–19th centuries — Ed.)

If not Italians, then Frenchmen.

Generals — if not Germans, then Ukrainians. The best general in Russia was Paskevich (Ivan Paskevich (1782–1856) — Russian general of Ukrainian origin. In 1849, he commanded the suppression of the revolution in Hungary — Ed.). Our wise men in Poltava erected a plaque to Paskevich a few years ago, as he was a famous fellow countryman. Nicholas I called Paskevich a commander, he served under his command. He ordered that Paskevich be given the same honour as the emperor himself. "Praise you, Paskevich!" was almost like an anthem. And the fact that Paskevich suppressed Hungary in 1849 is something that Orbán probably does not know.

I'm fine, I love both Clio and Euterpe. But they...

They specialise in one thing.

That's what I wanted to say, to put it mildly. And if he knew how Paskevich oppressed Hungary in 1849, while being the tsar's governor in Warsaw, he also oppressed Warsaw. That's terrible.

"I was at Stalin's funeral... They almost crushed us there."

I would like to pick up on what you said about Russian culture, Russian historical heritage. It has always been correlated with the imperial political idea. And in Stalinist and post-Stalinist times, we were forced to believe that this was precisely a liberal culture.

I was at Stalin's funeral.

You were at Stalin's funeral?

I was also there during World War II, by the way. And Stalin's funeral — I was studying at the Literary Institute (in Moscow — Ed.), and we were almost crushed there. It's a good thing that the guys pulled me out of the crowd into an entrance hall, because it was like the Khodynka tragedy, I can tell you. (About 100 people died in the crush at Stalin's funeral on 9 March 1953. It is compared to the Khodynka tragedy of 1896, during the coronation of Nicholas II, when almost 1,400 people died — Ed.).

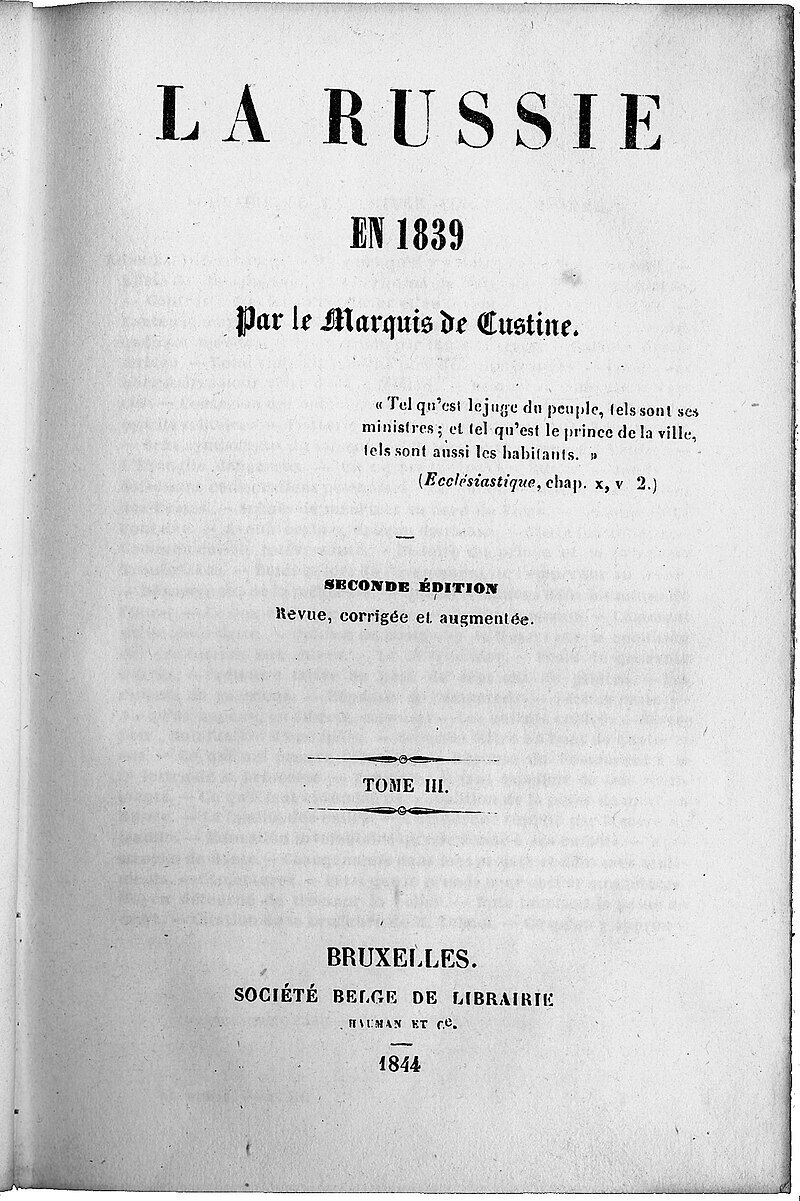

And then there was a very severe frost, and the Russian people mourned Stalin deeply. They needed to warm themselves up, so they danced right at the entrance to the columned hall. I will write about this someday. But they didn't feel like reading de Custine. (Astolphe de Custine was a French writer, traveller, and author of the book Russia In 1839, in which he critically describes the Russians' tendency towards arbitrariness of power — Ed.)

And what did they do right away? When someone like that came and then praised Russia, they published it all. Then they all sat in Europe. They all sat in Baden-Baden, Paris, Switzerland. They are buried there. Some were never transported. Glinka was transported, but Bryullov remained there under the cypress trees. (Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857) — Russian composer. Died in Berlin, reburied in St. Petersburg. Karl Bryullov (1799–1852) — Russian artist, buried in Rome — Ed.)

And how did the West know Russia? By the splendour of the facades in St. Petersburg, because Moscow was "merchant-like". They would arrive — the Mariinsky Theatre, great. Some Frenchman would stage a ballet — that meant Russian culture. And when Custine arrived and wrote, and Nicholas I did everything for him, he even gave him a Russian carriage, because Custine had arrived with an English carriage.

He probably wouldn't have made it.

But he arrived with a good carriage and loaded it onto a steamboat. It broke down after the first hundred kilometres. Nicholas I gave him a Russian one that wouldn't break down on their roads.

And he travelled around Russia for three months and wrote his piece. Everything was exactly as he wrote. And the Russians were so outraged that even the kind, good Zhukovskiy called him a dog (Vasily Zhukovsky (1783–1852) — Russian romantic poet). "How can you be such a dog?!" But it's all true, what can you say? And they found a way out. They said: ah, so Custine is a "homosexualist" (Lina Vasylivna deliberately uses an outdated word to refer to a homosexual man in order to emphasise Russian politically incorrect practices — Ed.). That is why he underestimated Russia. I analysed this point in my book.

And who was the famous memoirist Vigel? (Philip Vigel (1786–1856) — Russian memoirist. Next — a quote from Alexander Pushkin, "From a Letter to Vigel.") Yeah, you don't believe me, read Pushkin. "But, Vigel, have pity on my ass." Let's not talk about Tchaikovskiy, let's not... That's not an argument. That's filth, such an argument.

Incidentally, Uvarov, the founder of Russian ideology, laid the cornerstone of the ideology of "Orthodoxy, autocracy, and nationality." Read Pushkin: "Prince Dunduk sits in the Academy of Sciences." He is Uvarov's friend. Uvarov appointed Prince Dunduk. So why does he sit there? Why such an honour? Soviet publishers wrote "because there is something to sit on." But Pushkin wrote differently, "because... there is" (Prince Dunduk from Pushkin's epigram — Mikhail Dondukov-Korsakov (1794-1869), actual secret advisor, Uvarov's confidant. In the original epigram — "because there is an ass" — Ed.)

Do you understand? So they say that Custine is a "homosexual," yes, but what about Uvarov?

"When the Enlightenment was happening in the West, in Russia these bearded priests were still spouting their backward ideas."

So we are talking about Russia, and we are talking about the West, which in fact during the Enlightenment created its cornerstone, where freedom, brotherhood, equality, all these things that Europe was supposed to hold on to for the last 300 years. Where did that go? Why does freedom, a word that sounds sincere and natural to Ukrainians, sound like something foreign and full of pathos there today? Why don't they understand our need for freedom?

In the West, in Europe, there were very intelligent people, and they created a great deal. When the Enlightenment was happening in the West, in Russia, those bearded priests were still propagating their backward ideas. Perhaps their sense of freedom was nullified because they had it.

So, when you have it, you don't appreciate it, you don't notice it?

And that's dangerous, because when you don't notice it, and it goes on like that, generation after generation, suddenly the generations calmed down, they just lived well. How good it is that we feel bad, right? We don't have time to calm down.

I think we feel the need for freedom much more acutely now because there isn't enough of it, because they are trying to take it away from us.

And remember what it was like in the empire. No freedom.

And those who built the empire were not Ukrainians. When people tell me that they were Ukrainians, I say no. There were some among them, I wrote about this, for example, a certain Minister of Foreign Affairs, Troshchynskyy, who wrote a speech for Alexander I (Dmytro Troshchynskyy (1749–1829) — Ukrainian nobleman, patron of the arts. While serving the Russian Empire, he defended the idea of Ukrainian autonomy. He was probably the leader of a secret circle of Ukrainian autonomists — Ed.).

They were smart guys, but when they were on leave (resignation — Ed.) in their villages and farms, they had sabres hanging on their walls...

Mamai's Cossacks, obviously.

And somewhere there, History of Ruthenians appeared (History of Ruthenians — a political treatise by an unknown author from the late 18th — early 19th centuries. It describes the history of Ukraine from ancient times to 1769, focusing on the Zaporizhzhya Sich and the Hetmanate — Ed.). And where did it originate? It was found in the estate of Myklashevskyy (Mykhaylo Myklashevskyy (probably 1640–1706) — Starodub colonel, associate of Hetman Mazepa — Ed.).

Who was Myklashevskyy? He was from Starodub. He was a colonel in Starodub. He held very high positions, but he spoke Ukrainian. And Paul I sent him into retirement. Because there was longing for something. Kyrylo Razumovskyy was also longing for something. I think Andriy, who was a diplomat, was longing too. I don't think Oleksiy was. Oleksiy was already a courtier.

I think Hryhoriy, whom we know the least, was longing much. And he, this Lausanne philosopher, the son of Kyrylo Razumovskyy, the hetman, was a scientist. And he did not go to Russia. He has descendants. This very same Gregor Razumovskyy, who comes to Baturyn, is his descendant. I sent him my regards. I felt such sympathy for him. The relationship there was complicated. And all these guys are descendants of the Hetman. (Kyrylo Razumovskyy (1708–1803) was the last hetman of the Zaporozhyan Army. He was president of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences from 1746 to 1798. Andriy, Oleksiy, and Hryhoriy were the sons of Kyrylo Razumovskyy.

Andriy Razumovskyy (1752–1836) was a Russian count, diplomat, and patron of Beethoven, to whom the composer dedicated his Fifth Symphony.

Oleksiy Razumovskyy (1728–1803) — Russian count, courtier of Catherine II, Minister of Public Education of the Russian Empire, Freemason. Hryhoriy Razumovskyy (1759–1837) — geologist, mineralogist, biologist, founder of the Society of Natural Science Enthusiasts in Lausanne. He lost his Russian citizenship for openly criticising the tsarist system of Emperor Alexander I.

Gregor Razumovskyy (born 1965) — Austrian historian, political, public and cultural figure, count. — Ed.)

Alexey Konstantinovich Tolstoy — Russian poet. (Alexey Tolstoy (1817–1875) — Russian poet, count from the Tolstoy family, great-grandson of Kyrylo Razumovskyy, friend and student of Mykola Kostomarov (not to be confused with the Soviet author, Alexey Tolstoy).

"Amidst the noisy ball, by chance," what did he write? "Forgotten, descendants, our noble family." (Quote from Alexey Tolstoy's poem The Empty House — Ed.) I wondered what "noble family" he meant? He was the grandson of Hetman Razumovskyy.

One way or another, we are talking about the rise of the empire after the defeat of our statehood, after the defeat of our Hetmanate...

Mazepa said: "We stand, brothers, between two abysses." ("We now stand, brothers, above two abysses" — the beginning of "Hetman Ivan Mazepa's proclamation to the army and the Ukrainian people" — Ed.)

What year was that? 1686, when Poland and Russia signed the Eternal Peace (Eternal Peace of 1686 — a peace treaty between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Muscovite Tsardom, according to which the Hetmanate was divided along the Dnipro river). Think about it, Eternal Peace — with a capital letter. Poland and Russia. And what did they do? They divided Ukraine along the Dnipro, giving the Left Bank to Russia and taking the Right Bank for themselves. And Kyiv, I am very ashamed of the Poles, they sold it to Russia. And even the exact figure is known. And if they had not sold Kyiv, it would have been the capital and something would have been formed. But what happened? The hetmans on the Left Bank and here, this Doroshenko is rushing around, wanting to unite (Petro Doroshenko (1627–1698) — hetman of the Zaporizhzhya Army of Right-Bank Ukraine, head of the Hetmanate, participant in the Khmelnytsky Uprising and the Moscow-Ukrainian War of 1658-59).

Someone killed someone, someone... The boys are rebelling, how many of our people have been killed there. And after that, it was born, because, — oh, I'm quoting myself again: "because only nations revealed in the word," you understand, can be heard by the world ("Because only nations revealed in the Word can live with dignity on earth" — a line from Lina Kostenko's novel in verse Berestechko). Manifested in the word. And we were not manifested in the word, because we were not even heard where we were manifested in the word.

Lesya Ukrainka said to Machtet (Hryhoriy Machtet (1852–1901) — Ukrainian and Russian writer, revolutionary-populist. He wrote mainly in Russian — Ed.), in my opinion, that "you are an intelligent person, you can speak Russian."

That's what they told you when you were studying at the Literary Institute (in 1956, Lina Kostenko graduated from the Gorkiy Literary Institute in Moscow — Ed.): "Why are you writing in this language?"

Oh, don't say that. "Why do you need this language of Indian tribes?" That's what they said to me. But, thank God, there weren't only chauvinists at the Literary Institute, there were all kinds of people there. There was a party organiser who said to me, "What have you written?!" I wrote a poster for the celebration of the annexation, oh, the reunification ("The reunification of Ukraine with Russia" — a Soviet and Russian historiographical concept, historical myth, part of Russia's historical policy and state ideology — Ed.).

300 years, right?

Yes, 300 years.

They heard somewhere that I could draw, I hid it very well, I had to draw. So I wrote "300 years of accession." Chukreyev pounced on me. "What did you write, what is this? It was a reunification!"

I said, ‘reunification’ is diffusion. They stirred it up, stirred it up in one flask, and that's it. And there is no one nation or the other. Your Russian nation has also been completely eroded. Tell me, where is the Russian nation? It has melted into all the other nations. No, it has instilled its rudeness in everyone. And I say that annexation is a good thing. We annexed, so we can secede. God, what happened to me!

Our circles, there were Balts. I was friends with Balts, with Baltic women (in the USSR, the Baltic countries of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia were called "Baltic/Baltic States" — Ed.). That's Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia. And with Armenians, with Paruyr Sevak (Paruyr Sevak (real surname Kazarian; 1924–1971) — Armenian poet and literary critic. He took the pseudonym Sevak in honour of the poet Ruben Sevak, who died during the Armenian genocide — Ed.). They all understood.

Well, yes, it was way more obvious to them.

Yes, Paruyr Sevak understood all this. They were very good people. The Russians didn't understand anything, we didn't talk to them much.

Why do people abroad think that Russia has a great culture? I suddenly felt that emigration was like emigration from Russia! At first, everyone went there, and then they all emigrated. These are the best Russians! Bunin left — how can you not respect him? Stravinskiy, Dyagilev, everyone. How can they not be respected? (Ivan Bunin (1879–1953) — Russian writer, Nobel Prize winner in literature. Igor Stravinskiy (1882–1971) — Russian composer and conductor of Polish and Ukrainian Cossack origin. His key work is the ballet The Rite of Spring. From 1910, he lived in Europe and the United States. Sergey Dyagilev (1872–1929) — Russian theatre reformer, impresario, founder of the Russian Seasons in Paris — Ed.).

So they thought that this was Russian culture. Just think about it, who stayed? Why did they all flee from it? Rachmaninoff (Sergey Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) — composer, pianist, conductor of Russian origin. He played a prominent role in the formation of the Kyiv Conservatory — Ed.). Why did he flee Russia? Did he flee from great culture? I don't know of any confusion, any web of deceit, like the one Russia has woven.

It seems to me that the world simply does not fully understand what he is talking about. There is a beautiful facade, which is pleasant to look at.

When we were in Sicily with Ivan Dzyuba, we were performing somewhere, and the audience was nice and friendly (Ivan Dziuba (1931–2022) — literary scholar, literary critic, member of the Sixtiers movement, participant in the Ukrainian independence movement. Second Minister of Culture of Ukraine — Ed.). And suddenly, some face peeks out from somewhere and shouts: "Viva, Mayakovskiy!" He just couldn't stand the fact that there were Ukrainians here. You see, they've dug themselves in and don't want to think.

"When I see Kirill Gundyaev, as Hryhir Tyutyunnik said, “Laughter weighs heavily on my chest”

Very often there are stereotypes that there is a great Russia that absorbs everything, covers everything.

My argument is simple, and I wrote this book calmly, without getting carried away. Because you can't get carried away, you have to do it calmly.

Take, for example, one such fact. Osip Mandelstam, a Soviet poet (Osip Mandelstam (1891–1938) — a Russian poet of Jewish origin, an acmeist. Arrested for an anti-Stalin epigram. Died in a camp in the Far East. Buried in an unmarked grave — Ed.).

And in France there was a poet, only Yuriy Mandelstam (Yuriy Mandelstam (1908–1943) — Russian poet and literary critic, participant in the "first wave of emigration", member of literary associations in Paris. Died in Auschwitz — Ed.). And he was the husband of Stravinskiy's daughter.

A French poet and a Russian poet. Fates: Osip Mandelstam was killed. Arrested, killed, thrown into some pit so that no one could see where he was buried. And Yuriy Mandelstam was Jewish, and the Germans killed him as a Jew. The Germans killed him, the fascists — and then the communists killed him. And then somehow they had to leave a trace of him. Near his wife's grave, they put up a symbolic sign, what is it called? A cenotaph, right?

Where there is no actual burial.

There is no body, but there is a symbolic sign. And Yuriy Mandelstam is there. Does that say something or not? That is, the fascists killed him there, but the French still created a memorial. And here, how much do we know about Mandelstam — not a word.

And no one even thinks of condemning those who killed Mandelstam and thousands of Ukrainian poets at the same time.

I wonder if they will ever be condemned?

You know, when I see Kirill Gundyaev (Kirill Gundyaev (born 1946) — Patriarch of Moscow. He preaches the doctrine of the "Russian world." He is the ideologist of church militarism — Ed.), as Hryhir Tyutyunnyk said, "laughter weighs heavily on my chest" (Hryhir Tyutyunnyk (1920–1961) — writer, journalist, publicist, educator. Laureate of the Shevchenko Prize for the novel Vir — Ed.). He always said, "Laughter weighs heavily on my chest."

And I look at this Kirill Gundyaev. Is he serious? I'm not even talking about the fact that they bombed Russian Orthodox churches. But there are footage of how they blew up the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, destroyed by the Bolsheviks in 1931 — Ed.). They built a swimming pool in its place. How many priests were persecuted!

Chornobyl, for example, there is a village called Lubyanka. We always went there to visit people's graves. Because there you can hear and see a lot. And, by the way, our expedition filmed all of this there (since the 1990s, Lina Kostenko has been a regular participant in scientific expeditions to the Exclusion Zone, led by ethnographer Rostyslav Omelyashko. The expedition saved cultural heritage and documented the situation — Ed.).

Only our cameraman was exposed to radiation there and died. He was a wonderful guy. I'm standing there in Lubyanka. A woman comes up to me. She says, "Why are you going to Kyiv? All our houses are empty. Stay here. Look at the house, look at the hollyhocks growing!" So that's how it went, she said that it was my dacha. And someone started saying that Lina Vasylivna had a dacha.

On Lubyanka.

Yes, yes, on Lubyanka (‘On Lubyanka’ is a play on words, "Lubyanka" is also the name of the FSB building in Moscow — Ed.) And this woman said to me: "Now we can commemorate our loved ones and everything." She said that the police were standing there and wouldn't let us in.

They didn't let you into the cemetery?

Yes, they wouldn't let us in for the funeral. It's terrible. And now, you see, he's taking away our voice. And then he stands there with a candle.

Have you seen this 14th-century image? Oh, listen, so artists must have intuition. What should the devil look like? He doesn't necessarily...

You mean this image is known in Western Europe, right?

Yes, listen, it has Putin's features!

Yes, yes, yes, very similar.

So, you see, it's a bit scary.

"Defeat teaches us more than victory ever could... Where there is heroism, there is no final defeat. There is hope for future victory."

Lina Vasylivna, you mentioned Ivan Mykhaylovych Dzyuba. And I found a very interesting comparison in his work. He writes about your Berestechko and says that there are two epic works in our literature where, in fact, historical defeat is at the centre. But from this defeat, a certain vision of the future is built, a vision is built. These are The Tale of Igor's Campaign (The Tale of Igor's Campaign or The Tale of Igor's Regiment — a heroic poem of the 12th century about the campaign of the Rus' prince Igor of Novgorod-Seversky against the Polovtsians — Ed.) and your Berestechko. In fact, can a historical or recent defeat serve as a source of energy, a foundation from which something can grow?

Defeat — no victory teaches as much. Those were terrible defeats. Once, Yavorivskyy (Volodymyr Yavorivskyy (1942–2021) — writer, public figure — Ed.) spoke somewhere and said "shame on Berestechko" and so on. I put a note in his mailbox: "Do you distinguish between shame and tragedy?"

Berestechko was a terrible tragedy. How can you call it a "defeat"? They stood their ground to the end. They stood their ground! So many of them died there! I wrote about all this. The king himself was surprised and wanted to pardon the one who was waving his scythe, and so on. (The Polish king and Grand Duke of Lithuania, Jan II Kazimierz, commanded the armies of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the confrontation with Bohdan Khmelnytskyy's army, including in the Battle of Berestechko — Ed.)

You know, where there is heroism, there is no final defeat. There is hope for future victory. So Ivan was right here. He was right.

If we look at this war and some local defeats? For example, Mariupol, where our garrison was forced to surrender, but how much this actually united us.

Our garrison did not surrender. It did not surrender. The Supreme Commander-in-Chief ordered it to lay down its arms and evacuate. They left. This is a tragedy. They laid down their arms, said they were evacuated, that is, rescued. What happened next? There was Olenivka, where they were killed, then they were tried, convicted, and then it turned out that they were prisoners (The mass murder of prisoners in Olenivka was a terrorist act by the Russian occupation forces: on the night of 29 July 2022, at least 53 Ukrainian prisoners were killed and more than 130 were wounded – Ed.). It turned out that this was not an evacuation, but captivity. Who will be held responsible for this?

The question is open, rhetorical, and very painful.

It is a terrible question. And those women who protested all the time, demanded...

They are still protesting today.

They demand: Did you evacuate the boys? — Let them out. And there were a lot of them there. Something like over two thousand.

Yes, it was a large garrison.

And then in each group that was handed over, they exchanged, "tit for tat," so many for so many. That's how Tsemakh and Medvedchuk were exchanged (Volodymyr Tsemakh — a militant of the terrorist organisation DPR, involved in the downing of Boeing MH-17. In 2019, he was transferred to Russia as part of a prisoner exchange. He returned to the occupied territories of Donetsk Region. Viktor Medvedchuk is a traitor to Ukraine, closely associated with Vladimir Putin, a former politician and oligarch — Ed.).

Well, that's what they say. But how was it really...

By the way, we also need to ask who had the right to hand him over. A witness to this. Yes, they are handing them over in groups, but they surrendered the entire garrison. They surrendered the garrison. And they give 20 there, 30 there, 15 there, so you don't know whether they were returned or not.

Yes, how much is left, how much has been returned. The whole figure is blurred.

Yes, it's blurred. No one had the right to do that. These are painful things, after all. Just as no one had the right to allow entry into Ukraine within 24 hours.

Oh, ask something a little easier.

***

The original source of the publication is Radio Khartiya. Reproduction is possible only with the author's permission.

Stay tuned for the second part of the conversation, in which Lina Kostenko reflects on the Ukrainian cultural process of the last century and how it fits into the European one, and recalls dozens of artists of her generation.