Finding a language for remembrance takes time

Since 2022, we in Ukraine have been grappling with the challenge of how to process memory. The fact that we cannot instantly find a new language for commemoration is entirely normal.

Even those works now considered iconic in the context of remembrance were certainly not created overnight. This process took at least two decades.

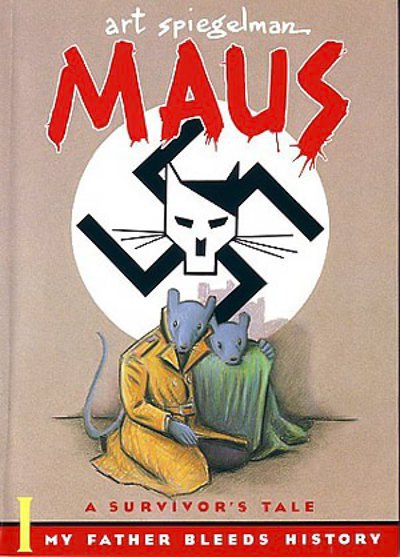

Take Art Spiegelman's graphic novel, Maus. This book represented a breakthrough in confronting the memory of the Holocaust, opening up new ways to recall those events. Or consider the film Shoah. It was made forty years after the tragedy, at a time when the subject was being addressed by people who, for the most part, had no direct experience of living through it.

It is significant that the breakthroughs in remembrance mentioned earlier are linked to the arts. Consequently, as we consider how to approach memory today, we invariably turn to the arts.

Here, however, it is crucial to recognise a distinction: while in a museum setting the principle that "the artist can do anything" might apply, the public realm introduces specific considerations when dealing with memory — factors that artists and curators must take into account. It is vital to remember why we are undertaking this work.

Strategic and Tactical Commemoration

At the Past / Future / Art Platform for Culture of Memory, we have formulated a distinction between strategic and tactical commemoration.

Strategic commemoration is that which operates over the long term, often with a certain distance from the event itself. It is a comprehensive set of tools — legislative, educational, and cultural — which create a perspective based on shared values and help society understand why a particular event is important.

Tactical commemoration, by contrast, refers to memory practices which happen here and now, responding to an immediate emotional reaction. These are acts of solidarity: to offer support, to demonstrate that we are not indifferent to the suffering of others, that we share their emotions, and that we seek to heal societal wounds.

In 2022, following the de-occupation of Kyiv Region, we were approached by architects, artists, and designers with ideas for memorials and art projects. Our initial instinct was to temper their enthusiasm: "The war is still ongoing, it's too early to be building memorials." However, after holding dialogues with local communities, we concluded that we should move in the direction of temporary memory initiatives.

Thus, today we are working primarily in the field of tactical commemoration, engaging with people who are far removed from the arts and acting as intermediaries between them and creative professionals.

Work on memory is impossible without working with the community

In matters of memory, the process is just as important as the result. Here is an example.

Kharkiv-based artist Iryna Vodolazchenko arrived in Izyum as a volunteer in 2022. She spoke extensively with locals on the ground and, after hearing their stories, suggested creating drawings on the wall of a destroyed building. The residents agreed and assisted her during the work. In this situation, the people living there felt that the artist’s action was a response to their pain, that she was sharing the experience with them. They perceived it as help, as a gesture of compassion, solidarity, and therapy.

Here is another example. An American artist and a Ukrainian artist decided to cheer up the local people in Bucha by painting sunflowers on destroyed cars. This caused a powerful wave of discontent among the local community, because someone had died in each of those cars. Perhaps people would have perceived this initiative quite differently if the first step had been to come and spend some time with them. But instead, some people came and made this artistic gesture. It should be noted that this was a serious humanitarian aid project aimed at supporting people in Ukraine. People had the noblest intentions and provided real help. But the artistic component of the project resonated mainly with people who were not local, but had no connection to Irpin, Bucha or Hostomel.

Both of these projects are similar in form, but radically different in process. Working with memory is impossible without working with the community. But often the position is: ‘We will create a brilliant project, and the local community will eventually grow into it.’ This is the case with the memorial in Yahidne, where the authors did not take into account the experiences of the people who survived in the school basement. This causes outrage.

Effective commemorative projects are often simple ideas

We are currently grappling with a tension: on the one hand, the necessity of accommodating the visions of those who have directly experienced these events, and on the other, the aspiration to create a high-quality cultural project. We must accept that at the stage of tactical commemoration, truly groundbreaking projects will be few and far between, and that is perfectly acceptable. Often, it is very simple ideas that prove to be the most effective.

Take, for instance, the 'Between Us' project by Nataliya Nekypilo. Activists placed plaques on park benches in Vinnytsya and Kyiv with inscriptions such as: "The one who gave their life for us could have been sitting here" or "The woman tortured by the enemy in captivity could have been sitting here." The idea was born after a cultural event where paper signs with similar texts were placed on empty chairs. For the initiator (Nataliya’s husband was killed in the war), this was a moment when she felt she was not alone in her grief.

When Nataliya was talking about this project, I noticed that she often used the word ‘carefully.’ We want to ‘carefully remind.’ That is, these people do not want to shout at anyone. They want to gently touch those who are hurting and carefully introduce this topic into the lives of those for whom, fortunately, it is not yet a personal wound. And I think this note of caution is very important. We must remember that our goal is not just to make something beautiful or show off the result, but to truly ease someone's pain. For commemorative projects, it is joint action that is important — not a beautiful form, not coverage figures, but joint action.

The table of remembrance is another initiative I would like to mention. It began in 2022 and is becoming more widespread every year. It involves placing a sign on an empty table in restaurants with the words ‘This table is reserved for the bravest among us.’

The memory of fallen soldiers is already part of our everyday life. We don't need to set aside a separate day or a separate space where we go to remember. When a person in Ukraine goes to a restaurant to eat, meet friends, drink a glass of wine, and there is this commemorative space next to them, it is normal for us.

In fact, this practice originated from a similar initiative that exists in the United States, but there it is done in military units. For them, it is the memory of the military about the military. In Ukraine, this project has been transformed and has become part of the public space. And, importantly, this practice is voluntary. Voluntariness is also an important characteristic of high-quality cultural practices related to memory, in my opinion.

Context is everything

Not every high-quality artistic product can become a high-quality commemorative practice. Here is an example: the monument to those killed by bombs in Dnipro, created based on sketches by Soviet sculptor Vadym Sidur, a native of Dnipro who lived most of his life in Moscow. In Soviet times, he was an innovator and created works that were unlike socialist realism. The original sculpture is a small figure (35 cm) that is truly powerful in its meaning and artistic language. However, it belongs to a different era, a different war and a different context.

When it was decided to install this work as a memorial to the victims of the Russian attack on Dnipro, there was a backlash. It is a proposal to honour the victims of the modern war using a form created by a Soviet artist in Moscow. This creates a sense of internal conflict, a schizophrenic effect, where content and form speak different languages.

An artistic gesture transferred to a commemorative space can change its meaning. Therefore, it is important to ask the question: why do we remember and what exactly do we want to say?

Any memorial should not only commemorate an event, but also tell a story — why this memory is important, who it is about, and for whom. The figure of Sidur works perfectly in a museum as a testimony to pacifism and anti-war humanism. But in the public space of a Ukrainian city that has survived a Russian missile strike, it sounds different — not like our history, but like someone else's.

Therefore, when creating commemorative projects, it is important to consider how the symbol will be interpreted, how it will be perceived by people directly affected by the events. Successful projects are always the result of collaboration and reflection, not just a gesture of goodwill. Memory is not an image, not an ideal artistic idea. Memory is a collective action.

Jamie Wardley and Andy Moss's project The Fallen was created in 2013 as a commemoration of the Allied landings in Normandy on D-Day. This event is usually depicted through heroic footage of American soldiers landing on the shore. However, the authors of this project focused not on heroism, but on the price of victory — the thousands of dead whose bodies covered the coast.

The artists created figures of fallen soldiers on the sand using stencils. This place has very strong tides, so within a few hours the waves washed away all the images. The temporary nature of the installation became its main meaning — the memory of the fallen is as fragile as the figures that existed for only a few hours.

It is important to note that the project was made possible thanks to hundreds of volunteers. The artists invited everyone to join in creating the figures, and it was this collective effort that brought the memory to life. Without people, this project could not have existed — and therein lies its most powerful gesture.

It is important to respect the opinion of local communities

Another example is the Stolpersteine (Stumbling Stones) project, which is now being implemented in Ukrainian cities. Its author is German artist Günter Demnig. The project covers dozens of countries and involves people in a joint commemorative gesture.

A Stolperstein is a small brass plaque embedded in the pavement near the home of a person for whom this address was their last before arrest or deportation during World War II.

Demnig's main idea is remembrance through personal action. No institutions or municipalities are involved in the project: each stone is the initiative of an individual. Anyone can find information about a victim, contact the Demnig Foundation, have the data verified, and finance the production of a plaque.

It is important to note that in some cities, local Jewish communities did not support the project, and it was not implemented there. This shows that even the strongest artistic idea cannot be more important than the will of the people directly affected by the memory.

Stumbling Stones is one of the most successful commemorative projects of our time. It reminds us that working with memory always requires consent, cooperation, and respect for the local context.

Ukrainian examples

I will talk about several successful Ukrainian examples of memorial and commemorative projects created during the current war.

I think most of you have seen photos of this memorial. But hardly anyone has seen it with their own eyes, because it was created on the territory of the Main Intelligence Directorate, which is off-limits to ordinary mortals. But in my opinion, this is a very important memorial initiative that could become a starting point for a new memorial language in Ukraine. This is the Memorial to the Fallen Intelligence Officers of the Main Intelligence Directorate, which was opened in June 2025. It was created by sculptor Nazar Bilyk.

Why am I mentioning him specifically? Because this is another example of joint action. Although the space is not public but military, the artist was invited and told: "You have no restrictions. The main thing is that it doesn't look Soviet." And how does the sculptor work with this idea? He creates space. The memorial is located between the DIU building and the exit. This means that when people leave work, it is easy for them to come here — they only need to take a few steps to the side, but it is convenient and natural.

Intelligence officers work with symbols, codes, and hidden meanings. That is why the memorial is built on symbols. In the centre is a stele with the inscription Aeternitas (eternity) in Latin and other languages. This is no coincidence: among the DIU intelligence officers, there were foreigners who worked and, unfortunately, died. There is also a hidden symbol: if you look at the memorial from above, it resembles an owl's eye, and the owl is the symbol of the DIU.

Another important detail is the plaques with the names of the deceased. They are not arranged in alphabetical order — they form the shape of an explosion. Each plaque is shaped like a chevron — a symbol that is easily recognisable to the military. The arrangement of the plaques with an allusion to an explosion (they are placed close together in one place, and then the density decreases) is also a gesture of awareness: the war is ongoing, so there may be a need for space for new names. The choice of material is also no coincidence: the memorial is made of fibreglass — the same material used to make drones.

Of course, this memorial could not be installed in a public space — it is not vandal-proof. Nazar Bilyk understood very well for whom and for what space he was working. This is an example of how important it is to consider the context when we create memorial or commemorative projects in semi-public spaces, museums or white cubes.

The next example is the project ‘In Memoriam of All of Us,’ created by Vitaliy Kokhan in July/August 2025. My colleague Kateryna Semenyuk was the curator, so I had the privilege of observing the creation of this project from the inside — from idea to implementation. It is a temporary commemorative installation created in Pivnichna Saltivka in Kharkiv, where there is not a single intact building.

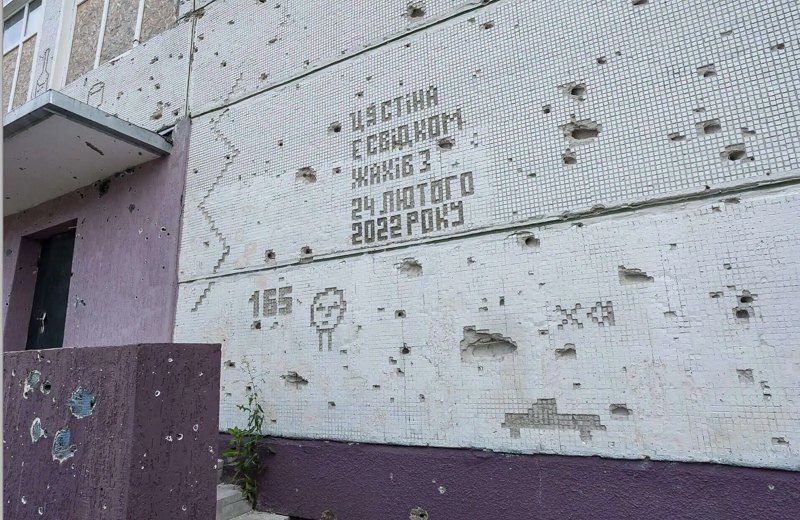

Vitaliy Kokhan is an artist who lived in Kharkiv for a long time. He noticed that the city has always been rich in text street art, and this inspired him. Many buildings in Kharkiv are covered with small tiles, a familiar texture that children often want to pick at. The artist decided to use this ‘technique’ and created inscriptions by knocking out tiles on the walls of a damaged school.

Everyone who approaches the installation reads their own meanings into it. It is important to note that this project could not have been implemented without the cooperation of local authorities and, most importantly, the school staff, who continue to work there despite the destruction.

While the installation was being created, local residents began to approach, ask questions, and tell their stories: where the tanks were, where the Shahed flew, how there was no water. The project began to accumulate memories and turned into a living process. The most valuable thing is that several people who were just passing by said, “They’ll repair it later. We need to preserve this installation somehow so that it doesn’t get knocked down.” And even if it doesn’t survive, the very emergence of this desire to preserve it is already an act of memory.

Vitaliy Kokhan, a public space artist, is aware that people have the right to come and make other statements in this area. That will also be perfectly normal. This is what living commemoration is all about — dialogue, joint action, readiness to react.

***

The Territories of Culture project is produced in partnership with Persha Pryvatna Brovarnya and is dedicated to researching the history and transformation of Ukrainian cultural identity.