Art cannot be outside politics. It is not just an integrated part of politics; it rather stands at the origins of power as a form of policy implementation. European empires established their control first in the form of cultural hegemony, and only then introduced their economic and physical (territorial, military, etc.) presence. Appropriation may be the very essence of art. Its syncretism, influences, borrowing, imitation are evidence of undisguised aggression, subjugation and sometimes destruction of the other in all and any its manifestations as far as the other poses threats to the monopoly of power with its own version of truth.

The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, acted as a catalyst for decolonization processes not in theoretical but in practical terms. The day before the bombing, I was sitting in the centre of Kyiv drinking coffee and reading an interview with Madina Tlostanova about the trivialization of decolonization. A well-known Russian researcher of postcolonial studies said that calls to decolonize everything in a row simplify the understanding of the process, nullify its outcome, and eliminate the radical potential of the theory itself. All that Madina Tlostanova managed to do after 24 February, as well as a large part of Russia’s “liberal-minded intellectuals”, was to stick the Ukrainian flag on their avatars, set a black background instead of a photograph, and write “no to war.”

This can be called the trivialization of war, its reduction to an amorphous idea, which yesterday’s critics of the Enlightenment project reluctantly analyse, while remaining typically “modern” people with their subject-object vision, often devoid of any empathy. In Russia, the culture of ”Dostoevsky” has really won, where murder is not only committed, but it is also justified from the standpoint of mathematics. Just as Rodion Raskolnikov belongs, physically and spiritually, not to himself but to the state, so every Russian intellectual today is involved in ethnocide (“denazification” in official Russian rhetoric). After all, politics is, as Dostoevsky notes, “thoughts that float in the air.”

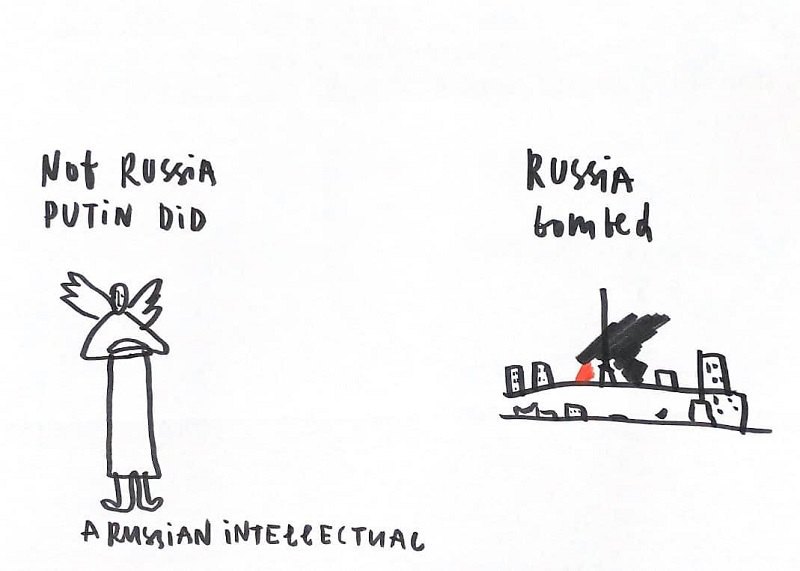

After a series of actions that launched the process of cultural “abolition of Russia”, some Russian intellectuals spoke about the existence of another (real) Russia. This attempt to preserve the monopoly of the metropolis in the world institutions, after the emergence of a new iron curtain between Europe and Russia, naively gives the culture a place of autonomous structure, which should begin the disintegration of the state itself: totalitarian, Putinist, “fascist” state. Thus, after the shelling of Babyn Yar by Russian troops (five people were killed in air strikes, including a Russian citizen), "Russian-born" art historian Ekaterina Degot wrote that the re-assassination of Holocaust victims was carried out “not by Russians but by Putin.”

However, Russian culture is nothing more than the result of long-term forced hybridization of subjugated cultures by the metropolis. Decolonization of Russia is impossible without the complete abolition of its culture. After all, under the guise of culture as a “soft power” in the most diverse manifestations Russia has exerted and continues to exert authoritative pressure.

Cultural visibility (representation) is usually possible only under conditions of strong economic infusions in the broadest meaning: from the material circulation of art to the establishment of market processes that link art production, art criticism, museum and gallery business, education, etc. The rhetoric within which the notion of “Russian culture” emerges in the post-Soviet and often global space is no less powerful in its overriding positivity than the rhetoric of "European art" in relation to traditional non-European cultures. While the raw materials of the colonies sustained the empire, it produced a culture of privileged ethnicity and (or) political class. Presence is stronger and more convincing than absence, while presence can be pointed out, it can be seen, it does not need additional explanations. The power of presence and availability is the rhetoric with which (un)consciously Russian intellectuals continue to constitute the imperial status of the state to which they belong.

Today’s discriminatory actions against Russian culture are seen by Russians and many Europeans as a crime against pluralism, which cannot be done with good intentions and undermines European democracy. However, such a sham position is a conscious speculation that vaguely asserts imperialism. Western intellectuals who hold such beliefs are compromising themselves by claiming, for example, that “Russian is the language of educated people in the former Soviet republics,” that “art is completely outside politics.” For example, Gary Morson, a Slavist at Northwestern University, willingly quotes Russian opera singer Anna Netrebko, who was fired from the Metropolitan Opera on 3 March 2022: “Forcing artists … to express their political views publicly and condemn their homeland is wrong. It should be a free choice. Like many of my colleagues, I am not a political person… I am an artist, and my goal is to unite people through political rifts.” I would like to remind you that in 2014 Netrebko, a “non-political person”, received a flag from the Speaker of Parliament of the so-called “DPR” and “LPR” – the “flag of Novorossia”.

In his text, Gary Morson says he does not understand why the concerts of Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky, lectures on Pushkin and Dostoevsky are canceled, even though they were born “long before Putin.” This misunderstanding (and consequently the reduction of the Russian-Ukrainian war to the guilt of one person) is another product of Russian colonialism, and at the same time a demonstration of the professional incompetence of many Western intellectuals. After all, most of them still think of the culture of existence, for which the metropolis has always spent enormous resources.

Here we can mention the political isolation in which Bolshevik Russia found itself after the February coup. European monarchs had strong interstate and (often) family ties with the monarchs of the Russian Empire. The Bolsheviks were considered illegitimate, especially given the de facto refusal of the Bolshevik government to implement the agreements concluded by Nicholas II. Today, however, for European and American researchers, both imperial and Soviet-imperial regimes have become quite legitimate. The gaps between them have been bridged by the tradition and culture of existence.

The traditional role of the university and its institutions also contributes to the establishment of colonial discourse. In this system, a Slavist who knows only Russian can claim to understand, study, and teach the entire culture of the Russian Empire and the USSR, can perceive Russia as their sole successor. Meanwhile, the study of the existing culture of (former) colonies requires a certain qualification and sometimes a completely different vision (methodology). After all, the Ukrainian culture of absence is the paradoxical absence of the consequences of the activities of all “dead [killed], living and unborn.” The “special operation” of the Russian Federation in Ukraine means the cancelled exhibitions, unwritten texts, destroyed works of art, redistribution of funding with its minimization in the field of culture, uncreated works of murdered artists. This is not the first time in the history of Ukrainian lands. This emptiness must certainly be turned into power: yes, it is emptiness, but it is not tainted with blood and lies.

However, at the same time, we must assert our right to the Soviet and imperial heritage, which in one way or another was created by people from Ukraine. As an example is the position on the building of the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale: the team of the Ukrainian pavilion in a text published on ArtReview reminded that the Russian pavilion was built at the expense of Ukrainian philanthropist and collector Bohdan Khanenko.

The aforementioned Ekaterina Degot, in her turn, offers the first steps in the reverse process, which would indicate the “complete destruction of the old” in Russia: “The Kremlin should not contain any form of power, it should be a place for citizens and tourists. The whole discourse of “Russia vs the West” must be rejected as toxic. The Tretyakov Gallery must, in its understanding of classical Russian art, reflect its consciously and unconsciously colonial, as well as anti-colonial nature. Racist and classist discrimination against people because of their provincial accent must be completely stopped. At least some Russians need to learn Ukrainian in order to speak two languages in Kyiv in the distant future.”

But even in this letter on the need to understand the colonial essence of culture, Mrs. Degot uses colonial vocabulary, calling Ukraine (and not only) a province. After all, even this “progressive” part of Russian intellectuals simply has no other language. In comments to the same post, Mrs. Degot notes that if the artist (Katarzyna Kobro, who was born in Moscow but grew up in Riga and worked in Vilnius, Belarus, and Poland) has used Russian all her life, she is obviously a Russian artist.

Thus, in keeping with the spirit of the “official” culture of the Russian Federation, which has long been a servile mouthpiece of “traditional” Russian values, unification is carried out by force. Through the language, and through the topology provided by the system – born here, so you are a Russian. And the whole idea of “another Russia'', which seems to be in exile and should be returned to Russian territory by Ukrainian bloodshed, is also just a mannered effort of the metropolis: “khokhly [derogatory name for Ukrainians] will come and build everything.”

For comparison, it is also interesting to look at the rhetoric of officials of Russian museum institutions. Hermitage Director General Mikhail Piotrovsky has already become a target for his close ties to Vladimir Putin. However, this is the problem of such a vision: Piotrovsky loses his name, he simply becomes the "director of the Russian Museum", which performs its function and exploits art in accordance with the interests and values of the state.

For example, the same Piotrovsky said a few years ago that the Hermitage preserves the best version of “Peter and Paul” by El Greco. That is, while European presidential candidates are recording the restitution of cultural values in the election program, Russia retains the status of a centrifugal metropolis, where the best (!) replicas of works converge. Provenance in the museum’s rhetoric means absolutely nothing, while French President Emmanuel Macron has officially stated that illegally seized African artifacts must be removed. He does not care about the further conditions of storage of these artifacts, because “it is important to break any, even a symbolic, connection with the imperial past.”

Since the beginning of the full-scale war of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, the Hermitage has made one post on social networks concerning Ukraine. On 27 February, employees posted a photo of a fragment of Ukrainian embroidery in the traditional imperial discourse: the art of the peoples of the empire.

***

The American sociologist Howard Becker proposes to consider art exclusively from the standpoint of “collective action” with the division of labour and the scheme of relations, which in itself is an economic redistribution and economic policy. With classical art, where the role of the creator is reduced to a craftsman, this is not surprising, with contemporary art some explanation is needed. On the one hand, contemporary art is subversive and involves an extreme measure of sociality, the intrusion of the critical into the existing social infrastructure. On the other hand, it is the art of radical expression of the author’s position. In both cases, the actual political field determines the nature of art: through direct invasion or exit.

That is why today the whole Russian culture becomes a totalitarian culture by default, even if artists were born long before “Putin”. This is because the context in which the culture of existence is located and the ways in which it found itself in that context are paramount. All the art and official rhetoric surrounding art in the Russian Federation is deeply Russian, deeply Putinist, if that is the case. After all, art is politics.