Cancel culture, which emerged with the #MeeToo and #BLM movements, became an active tool for influencing individuals, groups and communities, and later political parties. But now the ‘cancelation’ is being applied to the culture of the whole country for the first time. At least that’s what the critics of this approach, especially the Russians themselves, say with indignation. After all, sanctions work in two directions at once: on the one hand, Russian missions are no longer wanted at world cultural events, and on the other hand, Russian residents are also gradually being isolated from world culture.

Literature

In the literature world, the reaction of the international community first emerged in the form of statements of individual writers. On the first day of the war, Olga Tokarchuk supported Ukraine, and was later joined by Sofi Oksanen, Margaret Atwood, Frédéric Beigbeder, Yuval Noah Harari, Bernardine Evaristo, Joanne Rowling, Alison Killing, Witold Szablowski, Elif Shafak, Rupi Kaur and others.

The next step was the reaction of literary institutions: the Book Fairs in Frankfurt, Bologna, Warsaw, Prague, Brussels, Leipzig, Budapest, Guadalajara, Jerusalem, Gothenburg, São Paulo, Bogota, Taipei, and Seoul refused to cooperate with Russian publishers.

The world’s largest publishers, Penguin Random House, and Simon & Schuster, Gardners, the leading UK book wholesaler, Curtis Brown Pan Macmillan and Canongate have paused all dealings with Russian publishers. Powergraph, the Polish publishing house has renounced all contracts with Russia, and the Hemingway Foreign Rights Trust has banned the reprinting of Ernest Hemingway’s works in Russia. The Finnish Book Foundation has frozen all payments to grants for the translation and printing of books from Russia and will not provide new grants to Russians.

A number of writers and copyright holders have refused to publish and republish their books in Russia including Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, Lynnwood Barclay, Rebecca Kwan, Joe Abercrombie, Adam Przechrzta, Holly Black, Stephen Fry, John Crowley, James Morrow, Charles Stross, Jakub Ćwiek, Maya Lydia Kossakovskaya, Jarosław Grzędowicz, Marta Kładź-Kocot, Marta Krajewska, Arkady Franciszek Saulski.

I don't usually post pictures of myself, but today is an exception. pic.twitter.com/IvuiH3QVZv

— Stephen King (@StephenKing) February 28, 2022

Music

As in the case with writers, the music community has actively responded to Russia’s invasion, especially at the level of personal expressions. Madonna, Mick Jagger, Till Lindemann, Roger Glover, and David Gilmore released their statements of support for Ukraine; bands and individual artists began canceling upcoming tours in Russia (Iggy Pop, Twenty-One Pilots, The Killers, Green Day, Imagine Dragons, Bring Me the Horizon, Khalid, OneRepublic, Girl in Red, Judas Priest, Gorillaz, My Chemical Romance, Måneskin). Sting went further and refused to sing for Russians not only in Russia but also abroad, he will no longer entertain Russian oligarchs. And Pink Floyd removed their recordings from all digital music providers in Russia.

Spotify closed its office in Russia and canceled the possibility of a premium subscription for Russians. All the world’s largest record labels have left Russia including Universal Music Group, Sony Music Group, Warner Music Group. Furthermore, Russia has been banned from participating in the Eurovision Song Contest.

Similar processes are taking place in classical music. Conductor Valery Gergiev lost his leading positions in European orchestras and festivals (Munich, Paris, Vienna Philharmonic, Carnegie Hall, Edinburgh Festival, etc.). Numerous western concerts of pianist Denis Matsuev have been canceled. PIAS France label has stopped cooperation with pianist Boris Berezovsky, the Montreal Symphony Orchestra has cancelled the appearances of classical pianist Alexander Maloveyev, and Switzerland has canceled concerts by cellist Anastasia Kobekina.

Russian conductor Pavel Sorokin has been dismissed from the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. German conductor Thomas Sanderling has announced his resignation from the role of chief conductor and artistic director of Russia’s Novosibirsk Philharmonic Orchestra in protest against Russia’s aggressive military action in Ukraine. The Bolshoi Theatre’s music director and principal conductor Tugan Sokhiev has announced his resignation.

The annual Concertino Praga international competition does not feature Russian musicians, and the Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra and Zagreb Philharmonic orchestra have removed compositions by Tchaikovsky from their concerts. The Croatian National Theater has postponed the Russian Serenade concert indefinitely, Polish cultural institutions will no longer perform music by Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich, and Steinway & Sons grand pianos will no longer be sold in Russia.

Theater

In the theater world, the primary focus was on opera and ballet as the areas most integrated into state cultural policy. Perhaps the most notorious sanction here was the Russian soprano Anna Netrebko pulled out of the Metropolitan Opera and replaced by Ukrainian soprano Lyudmyla Monastyrska. The Bavarian State Opera, the Theater del Liceu in Barcelona and the theaters of Stuttgart, Hamburg, Zurich, and Milan also put their collaboration with Netrebko on hold.

The German Opera on the Rhine canceled the premiere of the opera directed by Dmitry Bertman, the Metropolitan Opera stopped collaborating with all artists of the Moscow Bolshoi Theater, choreographer Jean-Christophe Mayo withdrew his staging of the Taming of the Shrew from the Bolshoi Theater. Jacopo Tissi, the principal dancer for the Bolshoi Ballet has quit the company. Foreign artists such as Brazilian principal dancer Marcos Yago di Gonzaga, Finnish soloist Rasmus Ahlgren, and Japanese choreographer Tomone Kagawa have also resigned from the Perm Opera and Ballet Theater.

Performances by the Russian State Krasnoyarsk Opera and Ballet company were cancelled in theatres in Wolverhampton and Northampton, and the Helix Theater in Dublin canceled the performance of Swan Lake of the Royal Moscow Ballet. Performances of the Russian State Ballet of Siberia were canceled in Edinburgh and London, and tours of the Moscow Academic Musical Theater were cancelled in France. French choreographer Laurent Hilaire has announced his resignation from the position of artistic director of the ballet troupe of Academic Musical Theater.

The rector of the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet, choreographer Nikolai Tsiskaridze said that the Academy faced a mass exodus of foreign students and predicted problems in this regard with both staff and funding. The Anglo-Russian Opera and Ballet Trust, a UK charity set up to raise millions for Russian arts organizations under the auspices of the Prince of Wales has closed.

A similar situation, albeit on a smaller scale, is observed with drama theater: in particular, Polish theaters (Powszechny Theater, New Theater) refused to participate in the Golden Mask Festival in Moscow and canceled all Russian tours. Israel cancelled the planned tour of the Vakhtangov Theatre.

Cinema and TV

The most annoying of all cultural sanctions for ‘small Russian man’ was the decision of the world’s major production companies to halt the release of films in Russia. First, Warner Bros. canceled the premiere of the new Batman, then Sony paused their upcoming release of Morbius in Russia, followed by Paramount, HBO and Universal.

Disney not only canceled the release of its films in Russia, but also halted all business, including content and product licensing, National Geographic magazine, and local content production and linear channels.

Discovery Media Company suspended the broadcast of its 15 channels (Discovery, Animal Planet, TLC, etc.) and services in Russia. Eurosport suspended its operations and streaming Netflix has temporarily stopped all future projects and acquisitions in Russia, stopped buying Russian content and refused to broadcast 20 federal Russian channels.

Film professionals have painfully accepted the decision of leading film festivals not to admit Russian delegations. Such statements were made by the Cannes, Venice, and Berlin Film Festivals. The European Film Academy has excluded Russian films from the European Film Awards, and FIAPF has paused the accreditations of the Moscow International Film Festival and St Petersburg Message to Man International Film Festival.

Many Western actors and directors have made personal statements and donated money in support of Ukraine, including Benedict Cumberbatch, Leonardo DiCaprio, Mila Kunis, Ashton Kutcher, Jennifer Aniston, Emilia Clarke, Hilary Duff, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Steven Spielberg, Javier Bardem, Sean Penn, Kristen Stewart, Quentin Tarantino, Robert Pattinson and others.

Art

The most renowned international event in the art world – the Venice Biennale – will not represent the Russian Pavilion as planned this year (although the artists representing Russia themselves have withdrawn from the event in solidarity with Ukraine). In support of Ukraine, Documenta installed three banners with anti-war drawings by artist Dan Perjovschi (participant of the Documenta) on the facade of the Fridericianum.

Other upcoming art fairs in Europe, including Art Basel, Art Brussels, Miart in Milan and Spark in Vienna have also made statements condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine. They will also not represent Russian artists (but because they have not received any applications from Russian companies). The Liste Art Fair Basel gives away seats of Russian galleries that have withdrawn from participation to Ukrainian gallery owners, and the Art Dubai fair will transfer 25% of revenue from all tickets sold to help Ukrainian refugees who have lost their homes due to the war with Russia.

The art sales industry has taken a rather tough stance: its main players, Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Bonhams, have canceled their upcoming Russian art auctions.

There are numerous cases of the severance of ties with Russia in the museum industry. A group of Tate museums has severed ties with Russian oligarch donors Viktor Vekselberg and Peter Aven. The Bizo Group (an international organization that produces professional standards in the museum community) has excluded the Hermitage, the Tretyakov Gallery, the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Kremlin Museums from its membership. The Amsterdam and British Hermitages severed ties with Russia, and the Italian Ministry of Culture halted the Program of Russian-Italian cross-year of museums.

In addition, the German Foundation for Art and Culture (Bonn) required the Tretyakov Gallery to close the exhibition Diversity. Unity. Contemporary art of Europe. and withdrew its works from it. And the foundation of the artist Christian Boltanski pulled the planned exhibition in the Manege Central Exhibition Hall in St. Petersburg.

Expectations vs reality

The scale of cultural sanctions is impressive, though it is unjustified and premature to talk about the cancellation of all Russian culture. First, most of these restrictions apply only to officials of the Russian Federation (state institutions) and persons directly related to the government. For example, the Venice and Berlin Film Festivals are still ready to host Russian ‘independent filmmakers’, and the Association of British Orchestras has not supported a total boycott of Russian composers.

Secondly, a significant part of those producers of Russian culture who are able to produce something original are now emigrating en masse and finally changing their focus to Western consumers. Among them are those who have consistently disagreed with Kremlin policy since 2014; others change their shoes on the go and talk about the personal drama of sudden insight. But they all position themselves as victims of the Putin regime on an equal footing with Ukrainians – and this is how the Western community perceives them and offers them both moral support and new career opportunities. In particular, the prima ballerina of the Bolshoi Theater Olga Smirnova easily got a job at the Dutch Opera and Ballet Theater, the Saxon Opera in Dresden invites Russian musicians to collaborate, and Russian artists are welcome participants in artistic events dedicated to the war with Ukraine.

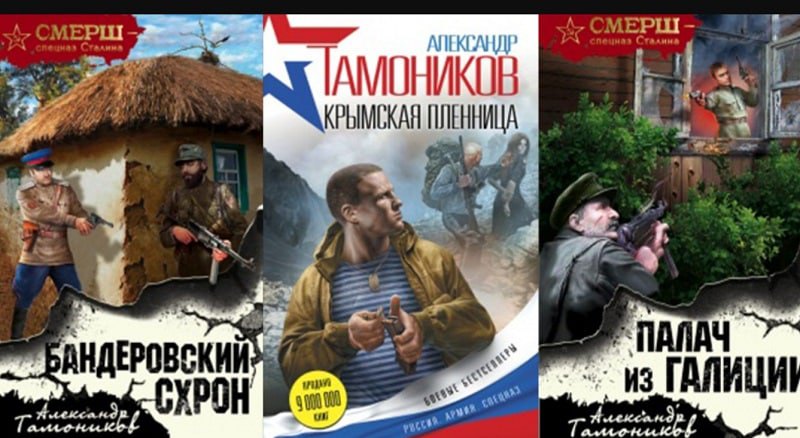

With the support of Western institutions, all these figures continue to legitimize the ‘real’, ‘non-Putin’ Russia – as if it exists somewhere beyond their imagination. It is as if they can disregard the fact that 70% of their fellow citizens support Putin's policy. As if art can be outside of politics. Here, particularly telling is the open letter to the world community by the general director of Eksmo, the publishing house in Russia, Evgeny Kapyev asking to rethink the boycott of Russian books. Kapiev talks about the high mission of literature, about developing a refined book taste, about how his work helps make the world a better place. Though at the same time, the products of Eksmo included an array of opuses with titles such as Palach iz Galitsii (The Executioner from Galicia) and Banderovskiy Eshelon (Bandera’s Echelon), which for years had been contributing to the formation of Russian public opinion.

Meanwhile, the official reaction to the cultural sanctions by the Russian authorities as expected is optimistic. The Chairman of the State Duma Committee on Culture Elena Yampolskaya noted that after the ‘closure of the spiritual McDonald’s’ it was time to fill the domestic film industry with senses and values. The pro-government media has already generated a recipe for these senses: “make a beautiful, positive product based on national self-respect without evil enkavedeshniks [men from NKVD] or insidious party workers and stop irritating the long-healed wounds of the GULAG.”

Meanwhile, in anticipation of the rapid emergence of cultural import substitution, Russian cinemas have begun (apparently out of habit) to show Swan Lake and Balabanov’s Brothers and Dead Man’s Bluff. The State Duma Committee on Culture proposes to create a code of ethics for cultural workers, which will define ‘what is good and what is bad’, and the speaker of the State Duma encourages the dismissal of all cultural workers refusing to openly support ‘Russia’s special operation’.

This rhetoric of triumph of the will once again inspires the comparison between Putin (who promised to finally resolve the Ukrainian question) and Hitler, and Putin’s Russia with Nazi Germany. But this comparison is not quite correct. After all, Hitler had many supporters and allies both among political leaders and among artists and intellectuals from different countries. While there are no strong voices in support of Putin outside of Russia. In particular, half-hearted and inconsistent though unanimous cultural sanctions speak for themselves. Although sometimes it seems that they are aimed not so much at ending the terrible war in Ukraine as at renouncing one’s own responsibility for it.