Occupation

A shell hit Olena's house back on 18 March. Windows flew out and the roof collapsed. When it happened, apart from Olena and her children, her parents and a 91-year-old old grandmother were at home. They were hiding in the bathroom because the basement of the house was flooded with groundwater. Olena got her arm wounded and another piece of shrapnel went through her thigh. It scratched the eldest daughter's forehead and tore off a fingernail, Yehor was wounded in the back. The wound was so deep that Olena felt as if she could see through it to his lungs. Olena's mother was wounded in the back and head. He father was injured the most. There were no pharmacies, no medical help either. The maximum the military could do was to bandage him and leave a small supply of medicines. Some medicine was brought in by neighbours, and so Olena and her children learned to cope on their own.

The children's wounds gradually healed. But her father's wounds were more severe. Eight days later the man died. Olena buried her father in her vegetable garden because that was the only option.

Until 17 May, when the Ukrainian defenders finally withdrew from Azovstal, Olena could hear heavy russian bombs falling on the plant. Sometimes they would fall into neighbouring areas. The streets were littered with shrapnel, remnants of shells and mortar tubes. At some point the local residents simply stopped noticing them. And there were fires blazing all around - they were put out by locals to cook food because there was no light or gas. According to rough estimates by the local authorities, there were about 100,000-130,000 residents in the city at the time.

"While I was still in town, they started supplying water," Olena recalls. "It was pouring down all the streets. Then, in the less damaged apartment buildings, the lights were being repaired. There were queues everywhere, I hadn't even seen such queues in my childhood. Everything was expensive. Under the shop there was wi-fi. I saw a bunch of people, I thought it was a queue for groceries but these were people catching the internet signal. They brought giant trucks to the market with screens telling people that Ukraine did not need Azov fighters or Azovstal. Some watched, some spat, some walked past.

Olena recalls that after a shell hit her house, she and her children lived in the basement of a neighbouring apartment building. A few days later, Kadyrov's people [russian Chechens] came to them, ordered everyone out and set up a firing position there. Olena returned home. Later, when the city was occupied, DPR [separatist Donetsk People's Republic] fighters began to station themselves in the house.

"They walked up and down the street asking who was left behind, why I hadn't left for Donetsk with my wounded children," says Olena. "They insisted that if I wanted, they could take me out. I told them I couldn't leave my mother, grandmother and relatives. They also wrote some lists, asked who had children, and mostly took people with children out. I had already learned to cope with my children's injuries, and I had a non-critical housing situation. But if it had been critical, I would have gone anywhere."

Closer to summer, there were announcements that a school was opening in the area. One of the six. The school where Olena's children used to go was bombed - the classes were destroyed, a hole all the way down to the ground floor. Around 50 parents came to the meeting. The children were enrolled as a formality, the parents say, because many of the documents were burnt. No one said anything about what education would be like. Neither Olena nor her children went to that school again.

Olena was also called back to work. They didn't say anything about money, only that from 1 June they were collecting people. She refused because she was planning to leave.

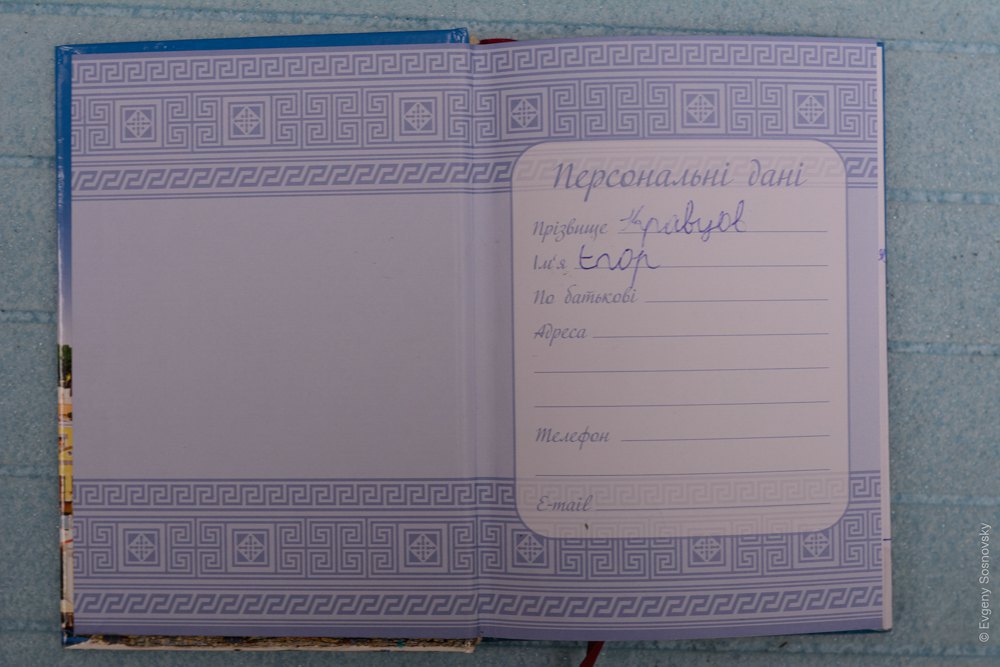

"I had no chance to leave earlier, and mentally I was not ready," says Olena. "But I understood that I had two children and that they had no future in the occupation. And we would not have survived the winter in the damaged house. At first we packed 11 bags, then we realised we couldn't carry everything. We took out the autumn and winter clothes. I took the icon I had beaded myself. The seven-stranded Mother of God. A small statuette I had brought back from a trip. I hid Yehor's diary between the children's books. So 38 years of my life in Mariupol fit into three bags.

Filtering

To leave occupied Mariupol, first you need to find someone who has transport. Olena did not want to take buses to russia on principle. Taxi drivers first agreed to take the family to Berdyansk, but then they either refused, changed their plans or said that their car broke down. Eventually one taxi driver agreed to take Olena and her children and mother. Four and a half thousand hryvnyas, or the equivalent in rubles for the trip. But in Manhush they were not allowed to go to the checkpoint without being filtered.

"Mum calls it castration," Yehor prompts, and his mother smiles lightly.

"It's as if all people living in Mariupol have to undergo filtering," Olena continues. "But why it's in the city, I don't know. In my opinion, they are just collecting a database of people. I went through the filtering only to leave."

Mariupol city councillor Petro Andryushchenko said that there are filtration points for those who want to leave the city in Manhush, Nikolske, Bezimenne, Starobesheve and Dokuchayevsk and Donetsk. There is no unified system of screening. There are also no guarantees of passing the filtering.

Olena and her family lined up for filtration in Manhush. They got No 7,000 in the queue. At the time, those who had numbers around two-thousandths were being filtered. Olena would probably have had to wait a month or so for the filtration, but as she and the children were wounded, they were allowed through without queuing. Olena's mother was given a pass without being questioned, only on written application, as she is already of old age.

The building where the filtration takes place is guarded by russian security forces. Olena and the children were interrogated by women. The interrogation takes place in one room where five people are brought in. A total of eight fives can enter during the day.

First you had to fill in a form with questions such as whether you helped the Ukrainian Armed Forces, whether you have weapons, whether you have a criminal record, whether you have relatives in the DPR or relatives in Ukraine, where you are going to live next, etc. The workers then collected fingerprints and palm prints and entered them into the database.

"They asked me if I had any tattoos. I said I had one, to remember the war," said Olena, pointing to the still unhealed wound from a shrapnel on her arm. "The atmosphere in the room was depressing. They growl: 'Give me your documents!' I give them the documents. 'Why did you give me all at once? What do you think I'm going to process all at once? Why are you fumbling here?' They keep people on tenterhooks for them to snap. They asked my daughter where she was registered, where she studied, where the scar on her head came from. She is an introvert girl, she sat and kept silent. They asked me if I had inadvertently intimidated her into not saying anything. They said if she kept quiet, she would not be filtered. I answered that the child was frightened and asked her to answer questions. In the end, we were given papers with stamps and the words "fingerprinted" on them. No one asked us for them beyond Berdyansk.

Men in filtration centres are interrogated and examined more harshly. When they check their phones, they ask about the contacts' names, peaople pictured in the photos and ask provocative questions. Since Mariupol had been without communication and internet for a long time, not everyone had time to clean up their messengers before being filtered. And even if they do, during the interrogation, the russian special services connect the phone to their computers and can restore deleted information.

Little is known about what happens to people who have not been filtered. For example, in June, the BBC published a story about men who were interrogated in Bezimenne. After they failed to pass filtering, they were sent for interrogation by the FSB. They were denied access to their relatives, punched in the face, kicked in the body and asked about links to the Ukrainian authorities. The next morning, one of the men and two women were transferred to a filtration colony in Starobesheve. There were 24 people in the cell. The man was released after four days and additional interrogation, so he was able to get out into controlled territory. Other men in the BBC story noted that they and their relatives in Bezimenne had been tortured, in particular by electrocution. A total of over 30,000 Mariupol residents may be held in filtration prisons and colonies, according to the Ukrainian authorities.

Ukrainians undergo similar procedures in the occupied territories of Kherson, Luhansk or Kharkiv regions, where is reportedly no filtering.

"Conditions are created in the occupied territories where people simply cannot escape filtration," said Stas Miroshnychenko, a journalist with the Media Initiative for Human Rights. "A filtration camp is not necessarily a tent city. It can be a military commandant's office of the occupying authorities, and a person is obliged to pass through this commandant's office. Whereas at the beginning of the war, for example, in Kherson Region, the occupiers interrogated mainly activists, veterans, people involved in the military, territorial defence and so on, it is now clear that the resistance against the occupation is massive. Therefore, the occupying authorities have to put all people through a filtering process to expose the disloyal.

The occupying authorities have recently been asking Ukrainians to sign a statement during filtration that they have "suffered from the Ukrainian army". These statements can be used by the russians for propaganda purposes, for example during show trials of captured servicemen. Human rights activists point out that such documents have no legal weight in Ukraine because it is another tool to put pressure on residents of the occupied territories.

At the end of March, the Ukrainian authorities started to receive the first reports of Ukrainians who had been forcibly removed to russia. People sought either to leave for another country or to return to Ukraine. At first, it was unclear how the Ukrainians ended up in russia in the first place, as no one would evacuate them there. And later, the Ukrainian authorities started talking about the first cases of deportation.

Deportation

Maryna was taken from Mariupol to russia in March. There was no communication in the city and information about the evacuation was hearsay. A neighbour told Maryna that evacuation buses were coming from one of the streets and she and her children decided to try to leave. When Marina and her children boarded the bus, she realised that they would not be going to Ukrainian-controlled territory.

"First they brought us to Nikolske," Maryna told LB.ua in early April. "We were sitting in buses the whole time. We were not told that we were going to russia. Then they checked our documents, looked for tattoos and asked about our attitude towards the Ukrainian authorities. We moved to other buses and left from there to Taganrog. There were a lot of people in civilian clothes, probably volunteers, asking if we needed accommodation. Some of the people were taken away to settle somewhere. We said we had relatives in russia and were given train tickets. The train ran off schedule and almost without stops. We didn't make it to the terminal station. We got off at a stop, and at the train station we got tickets for St. Petersburg, where we knew someone. No one checked us further on."

Former Ukrainian ombudsman Lyudmyla Denisova said in an interview with LB.ua that the deportation of Ukrainians started as early as 18 February. In fact, "evacuation buses" left the occupied territories for Rostov at that time. Residents of Donetsk, who agreed to be evacuated, told LB.ua that dispatchers on the hotline and officials of the occupying administrations who were taking down the information on everyone boarding the buses promised that they would be accommodated in sanatoriums in Rostov Region.

In spring, Ukrainians who were being taken out of the occupied territories of Donetsk Region were put in camps for the duration of the filtration process before being taken to russia. There are people who have been in such camps for months, waiting for their turn to leave.

In the case of Donetsk Region, people are first taken to the checkpoint and from there to the border. If it is a massive relocation by bus, in Taganrog they are accommodated for a day or two in temporary accommodation facilities. This could be anything from a sanatorium, hostel, tourist camp, gym, or train station. Often people are given russian SIM cards and taken to Rostov where they are put on trains to other parts of russia. These trains are called evacuation trains, but in fact they are deportation trains. They don't go according to the timetable and people have no choice where to go.

At the checkpoints, people have to go through all the same procedures as at the filtering point before they can leave. Interrogations are carried out by FSB representatives or russian border guards working for the FSB. People may be questioned, searched and detained for hours.

Sofia*, 42, was leaving occupied Melitopol with her two disabled children. At first, she did not think she would have to flee, but as time went on, rumours began to circulate in the town that the young boys would be forcibly mobilised into the russian army. Sofia's eldest son is 16 and a minor, but he looks more mature. The woman was afraid that russian soldiers might draft him straight from the street, so she decided to run away.

They left in April via Crimea because the family was afraid they might come under fire, as russian troops are constantly shelling the evacuation routes to the controlled territories. There were 16 russian checkpoints along the road. On the administrative border with Crimea, the occupiers searched her belongings, checked their phones and laptops, and offered to surrender her Ukrainian passport. Sofia replied that she first wanted to go to her relatives, and would make a decision later.

"In Dzhankoy, we took the train to Moscow straight away," says Sofia. "As soon as we arrived, two policemen and two plainclothes FSB officers came up to the carriage. They had lists of people arriving from Ukraine and were looking for men and boys of conscription age. They screened our suitcases, emptied our pockets, and let us go. We didn't stay in russia because we knew that the hotel administration informs the special services when Ukrainians check in. So we went straight from the train to the bus station."

Russia

Back on 12 March, the russian authorities published a resolution on the distribution of Ukrainians in russia. Voronezh Region – 7,000 people, Murmansk Region - 2,452 people, Krasnodar Territory - 5,330 people, Republic of Buryatia - 1,402 people, Moscow - zero, and so on.

Ukrainians who find themselves in russia have two options - try to leave for neighbouring Estonia, Lithuania, Georgia, Finland, etc., or stay and become hostages of the Kremlin. That said, there's not always a choice, because when people arrive in russia, they are put in temporary holding facilities if they have nowhere else to go. There are places where you can move around freely. And there are places where outsiders are not allowed at all, and often people don't even know that they have a chance to leave.

"The russian side has said that there are two million Ukrainians who left for russia. But you have to understand that this is the number of crossings across the border which the Ukrainian side does not control, while the russian side continues to control," Human Rights Centre ZMINA advocacy manager Olena Lunyova said. "But they never record how many people left russian territory, returned to the occupied territories or went abroad. Therefore, we should not rely on these figures. However, temporary accommodation centres have been set up in russia. They exist in many russian regions and in Crimea. At the end of April, russia said publicly for the last time how many people were living in these sites - only 33,000. This is not comparable to the millions who have allegedly arrived."

People have been and continue to be deported from Donbas, Luhansk and Kharkiv regions. Earlier, deportations to russia and Belarus were also recorded in Chernihiv and Kyiv regions. There are still Ukrainian diplomats working in Belarus to help Ukrainians return home.

Olena Lunyova points out that the number of people who have left for russia is not the same as the number of deported. Because deportation as a crime must be documented through open criminal proceedings and existing coercion and other indications. People were forced to go to russia because russia created such conditions. This is coercion to move. But most of the people were able to leave russia afterwards (except for those who have nowhere to go, no documents or money). This category includes, for example, children.

In an interview with the LB.ua news and analysis website, the secretary of the working group of the presidential office for the life and safety of children in wartime and post-war periods, Darya Herasymchuk, said that the National Information Bureau recorded 5,090 reports on the deportation of children. Human rights activist Olena Lunyova said that children from boarding schools in the occupied territories were taken to russia on 18 February. It is easier to apply for russian citizenship or to start the adoption process in russia on behalf of parentless children.

Patients of psycho-neurological boarding schools have also been removed from the separatist-held territory of Donbas. At the same time, there is no confirmed fact that adults from the psycho-neurological boarding schools were deported from the occupied territories after 24 February.

Lunyova adds that temporary accommodation centres are now being closed in all territories of russia.

"For example, in Khabarovsk Territory, people living in a temporary accommodation centre have been notified that they have to leave because it is closing down. What are people being offered? They are offered to move closer to the border with Ukraine or look for other accommodation. Plus, people have started returning to the occupied territory in Volnovakha, Mariupol, etc. After all, russian propaganda lies that occupied cities are being rebuilt at a superfast pace. In other words, people do not understand the state of things and return. Thus, russia's attitude towards Ukrainian citizens is clearly visible because Ukrainians are not needed in russia at all. Such 'evacuation' was necessary for russia for a while, to show on TV that 'people are running away'."

The road to freedom

People without documents who have been forcibly removed often do not even have money to leave, as Ukrainian cards do not work in russia. Human rights activists and volunteers strongly advise not to sign any documents or applications for refugee status, not to give the remaining documents to anyone, and not to engage in any discussions with anyone. Instead, contact someone who can help with money and leave at first opportunity.

The situation at russian checkpoints on the border with Estonia, Lithuania and Finland also varies. At some russian checkpoints, Ukrainians are released quickly after their documents have been checked. But more often people have to go through repeat interrogations, searches and pressure, and stand in line for hours. Men of conscription age are checked more thoroughly. Sometimes a person may be detained for no reason and not tell his family where he is. If a person is detained for a few days and released, it is possible to cross the border. But there are cases when people disappear without a trace. Then lawyers in russian pre-trial detention centres try to find them.

For most people leaving the occupied territories, russia is a transit country. They do not stay there, but go on their way. At the same time, people who were forcibly removed without documents or money often see no one else but russians in the temporary accommodation centres, because no one else is allowed there. Consequently, russia is a trap for them.

***

Sofia from Melitopol was able to leave Moscow for Lithuania. They are now in Denmark. The sons graduated from a Ukrainian school via distance learning. Sofia is now applying for a permit to work in Denmark. Sofia's parents are staying in occupied Melitopol.

Maryna from Mariupol also left St. Petersburg for Lithuania after her deportation. She has already found a job and is setting up a new life in the new country.

Olena from Mariupol with her son, daughter and mother came under fire while driving from Berdyansk to Zaporizhzhya. This happened not far from the checkpoint in Vasylivka, where the russian military regularly shells evacuation vehicles. Together with other evacuees from Mariupol, they lived in Zaporizhzhya for a week before taking a train to Kyiv. Their house in Mariupol is now occupied by neighbours who lost their home.

"I hadn't thought about Europe. And who knows there will be no russian missiles there either?" says Olena. "Kyiv is not my home, but there are relatives, friends and relatives. Three years ago I came to Kyiv on a business trip and felt at home here. Now I am here, I like the city, especially in the evening, but I constantly compare it to Mariupol. I walk down the street smelling roses and thinking what roses I had. I am waiting for Mariupol to become Ukrainian, to go back there. Everyone who left, with whom I am in contact, feels the same. We would go back there to rake up what's left of it with our bare hands. Just to go home."

*Names marked with an asterisk in the text have been changed at the request of the characters