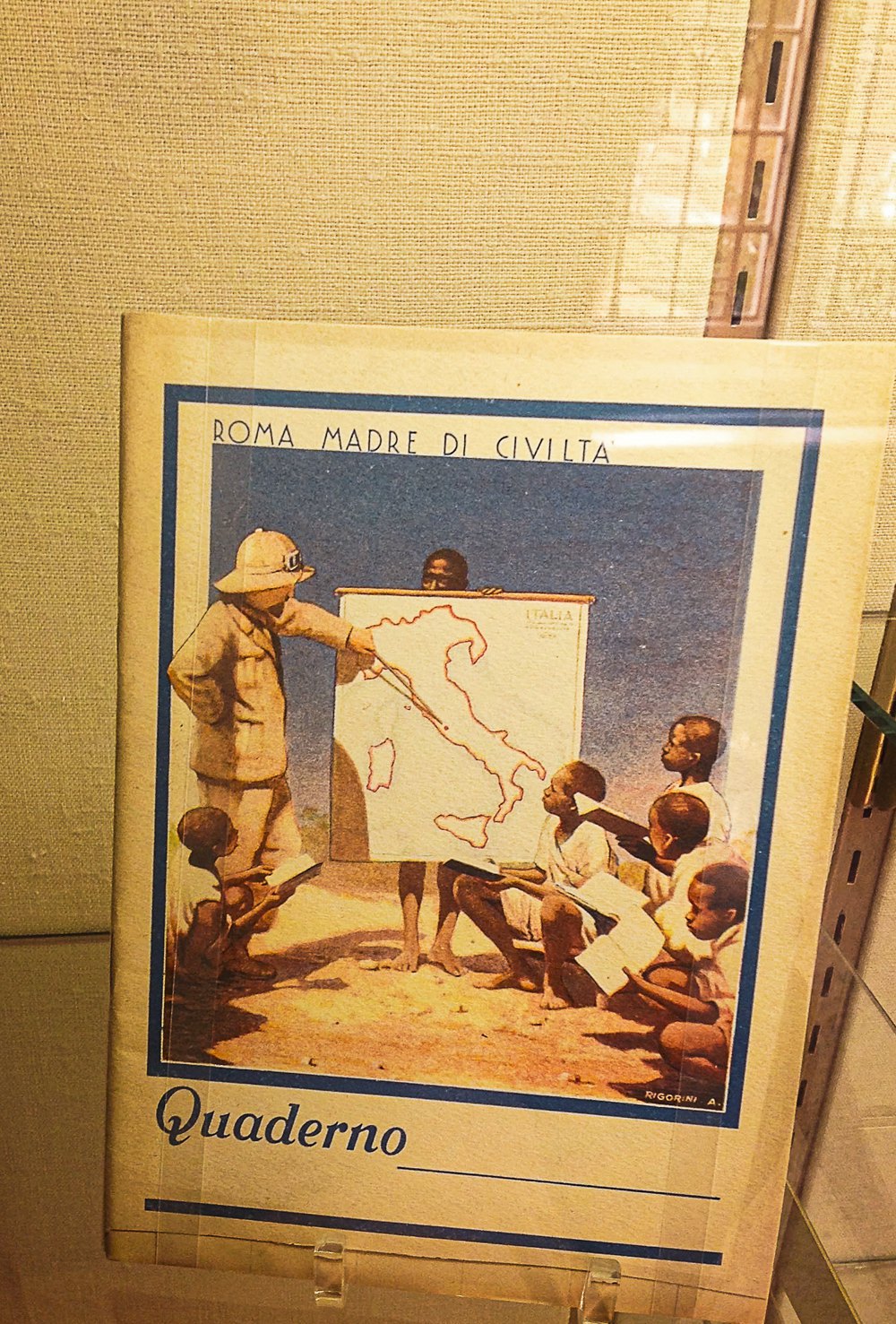

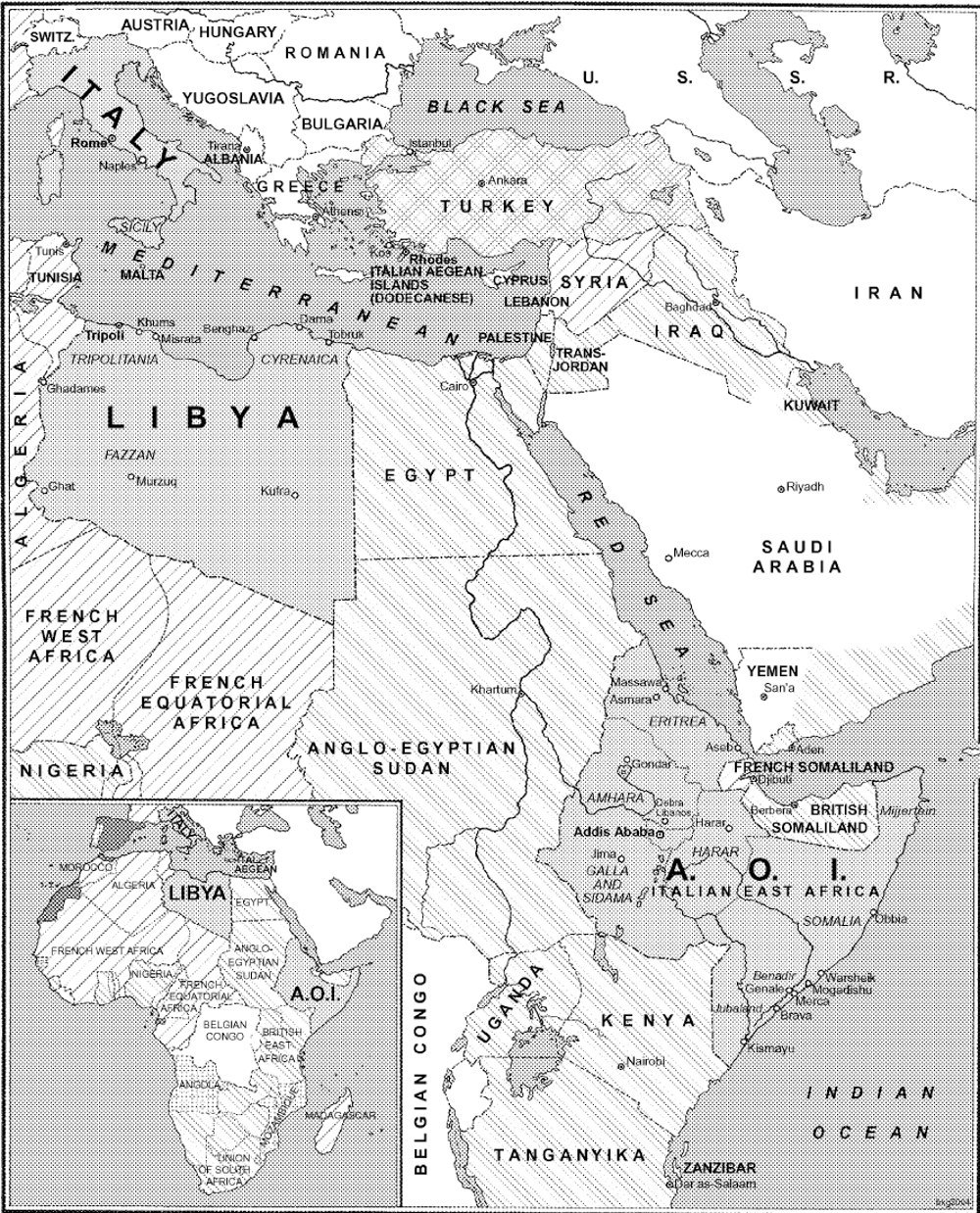

When the international community turned a blind eye to this occupation, Mussolini expanded his Italian world into Libya, Albania, and the Greek islands of the Ionian and Aegean Seas. The peak of this expansionist drive was his brutal war against Ethiopia, launched in 1935. Ethiopia was the only African country not colonised by a European power. The brutality of this war parallels Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Mussolini ordered the use of mustard gas, despite having ratified the 1925 Geneva Protocol banning chemical weapons. Italian forces sprayed the gas not only over Ethiopian trenches but also over villages, fields, hospitals, and even Red Cross positions. At the same time, Italy established a representative office at the Red Cross headquarters to spread propaganda about alleged Ethiopian war crimes - much like how Russia now accuses its victims of its own actions.

By uniting conquered Ethiopia with Eritrea and Italian Somaliland into Italian East Africa, Mussolini aimed to forge an alliance with Nazi Germany and carve a corridor between his territories in the Horn of Africa and Libya. His ultimate dream was to transform the Mediterranean into what the Romans called mare nostrum - “our sea”. Similarly, Putin seeks to control two “seas of his own”: the Azov and Black Seas, linking occupied Donbas with Crimea. Mussolini’s ambitions rivalled those of Julius Caesar. Yet, he met a far humbler fate - hanging upside down at a Milan petrol station. Italy, after his downfall, became even smaller than before his rule.

Mussolini’s regime became a model not only for Putin but also for several European right-wing dictatorships that survived after the Second World War. Until the mid-1970s, three such dictatorships remained in Europe: in Spain, Portugal, and Greece. Like Italian fascism, they shared strong anti-communist and nationalist ideologies. However, a key difference set them apart: while Mussolini sought to turn the state into a new church, marginalising traditional religion, Francisco Franco, António Salazar, and Georgios Papadopoulos aligned themselves with the traditional church, which fully supported their regimes.

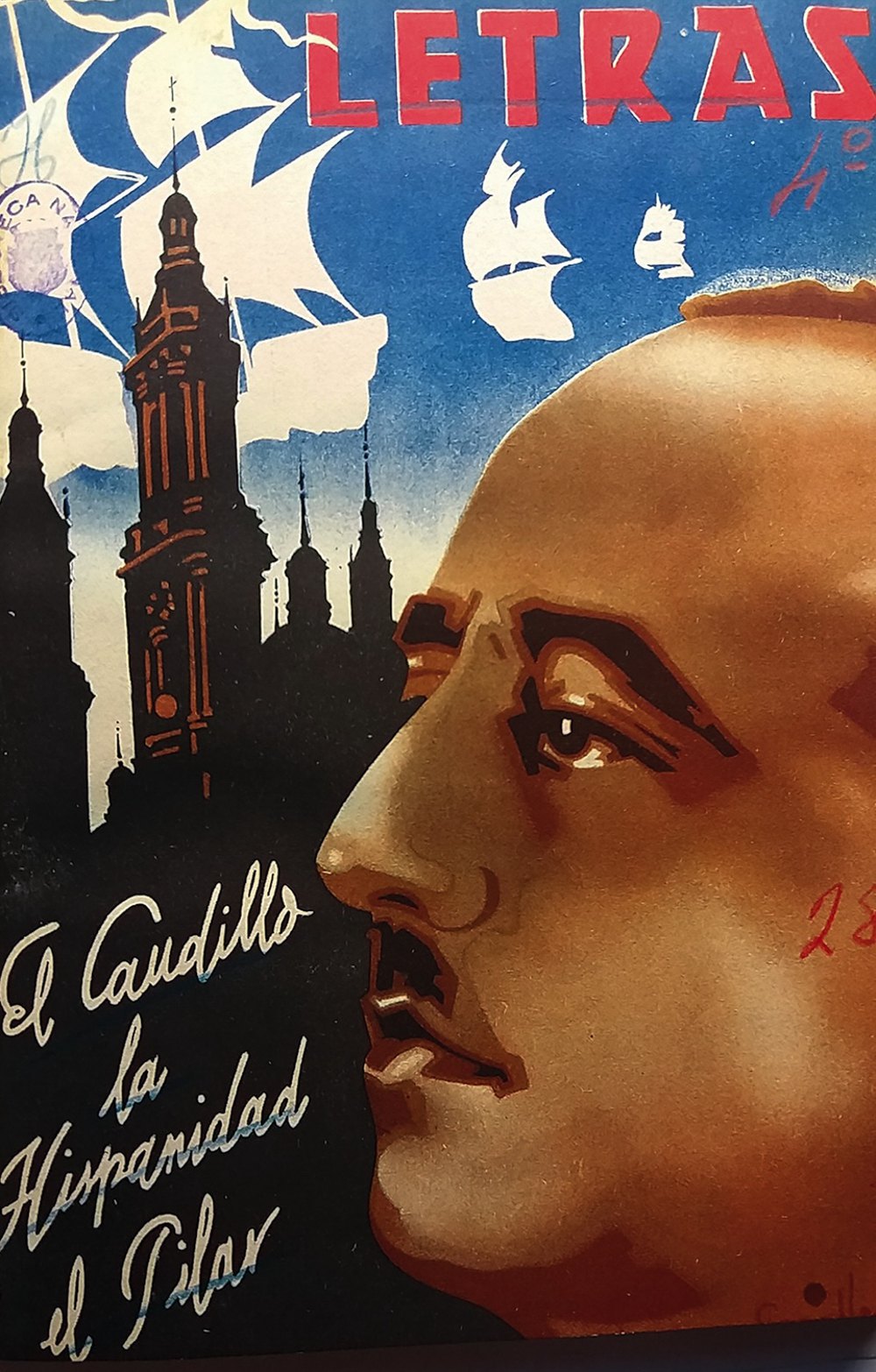

Like Mussolini, each post-war European dictator sought to build his own “world” - a grander version of his own nation. Franco constructed Hispanidad, glorifying Spain’s colonial history, the Age of Discovery, and its empire in Latin America and the Philippines. This is akin to Putin’s mythical “Holy Rus”, central to his Russkiy Mir (Russian World) ideology. For both leaders, the church played a crucial role in shaping colonial mythology. Franco used Spanish Catholicism to legitimise Hispanidad, just as Patriarch Kirill now promotes “traditional values” to justify Russian imperial ambitions. Even their methods align: before launching his wars, Putin created the Russkiy Mir Foundation in 2007 to promote Russian language and culture worldwide - just as Franco established the Hispanic Council in 1940 for the same purpose.

In the end, Franco turned the ideology of Hispanidad into a tool to defend Spain’s remaining colonies: Morocco, Spanish Sahara (now Western Sahara, with an ambivalent international status), and Spanish Guinea (now Equatorial Guinea). Appealing to Hispanidad, he sought to convince the world that Spain’s colonial presence in Africa was fundamentally different from that of Britain or France. He argued that the alleged cultural affinity within the Spanish world made decolonisation akin to tearing apart a single civilisation. However, these appeals failed, and Franco ultimately lost control of all Spain’s colonies.

Maintaining colonial rule through the notion of a shared civilisation was also a key principle of the Estado Novo (New State) in Portugal, founded in 1933 by António Salazar. While this regime had much in common with other right-wing dictatorships in Europe, it diverged significantly from both Italian fascism and German Nazism. Unlike Mussolini and Hitler, Salazar did not embrace right-wing radicalism but sought to contain it. While Franco ruled through a military dictatorship, Salazar distanced himself from militarism, keeping the army firmly under his control. He no longer placed faith in the power of the masses or the military but in the wisdom of the elites. Yet, this supposed wisdom did not prevent Portugal from sliding into authoritarianism, which was ultimately overthrown in 1974 by the Carnation Revolution.

Salazar clung to his colonies even more tenaciously than Franco, justifying it through an ideology similar to Hispanidad. The Portuguese equivalent of the Spanish world was called Lusotropicalism, derived from Lusitania, the ancient Roman province that once covered modern Portugal. Like its Spanish counterpart, this ideology romanticised and mythologised the Age of Discovery, when Portugal was one of the most powerful colonial empires, controlling maritime territories from the Azores to Brazil, Angola, Mozambique, Goa, Macau, and Nagasaki. Lusotropicalism claimed that Portuguese colonialism was unique - divinely sanctioned and imbued with an imperial mysticism (mística imperial). According to Salazar, Portugal had a God-given right and ability to colonise other peoples without racism or violence. The messianism underlying this ideology closely resembles the messianism of Putin’s Russkiy Mir (Russian World).

However, as with Russia’s imperial rhetoric today, romantic declarations were one thing - reality was another. And the reality of the Portuguese world was brutal. Salazar’s remaining overseas empire - Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, and East Timor - began fighting for independence, and the Portuguese dictator responded with ruthless repression. The most notorious symbol of this brutality was the concentration camp on Santiago Island, now part of Cape Verde.

Initially, the camp was used for political dissidents from mainland Portugal. Authorities chose the most isolated location possible, devoid of water and human settlements - ideal conditions for prisoners to lose their sanity and die unnoticed. It became known as the “slow death camp”. The camp doctor, Esmeraldo Paix da Prata, reportedly stated: “I am not here to treat, but to sign death certificates.” Prisoners who resisted were subjected to the frigideira (“frying pan”), a cell where temperatures reached 60 degrees Celsius during the day, with detainees confined there for weeks.

Later, anti-colonial fighters from Angola, Guinea-Bissau, and Cape Verde were also imprisoned in the camp, each group housed in separate barracks.

For rebellious prisoners, a “small Holland” was built - Holandesa, a cell within a cell that replaced the frigideira.

The camp on Santiago Island became a microcosm and a powerful symbol of Salazar’s Portuguese world - an imperial vision that, in essence, mirrors Vladimir Putin’s Russian world, albeit with less brutality.

Salazar fought tooth and nail to maintain control over his colonies until the Portuguese army itself decided to end his exhausting and futile colonial wars. It was the military that launched the coup that transformed into a peaceful revolution. In the end, the Portuguese world collapsed, burying the regime that had nurtured it under its ruins.

A similar fate befell Greece, where the so-called Junta of the Black Colonels ruled from 1967 to 1974. Lacking overseas colonies, this regime pursued an expansionist policy, seeking to establish control over Cyprus. The island had gained independence from the British Empire in 1960, with its first president being Archbishop Makarios III, the head of the local autocephalous church. As the colonels sought to impose their version of a Greek world, Makarios III stood in their way. They attempted to remove him, creating an opportunity for Turkey to intervene, sending troops into the northern part of the island and establishing an unrecognised republic - akin to the so-called DPR and LPR in Ukraine.

The junta’s expansionism and the resulting occupation of northern Cyprus soon provoked a student uprising, known as the Polytechnic Uprising, which began at the Athens Polytechnic University.

Thus, yet another self-proclaimed “world” became the grave of the regime that had created it. There is no reason why the Russian world will not meet the same fate.