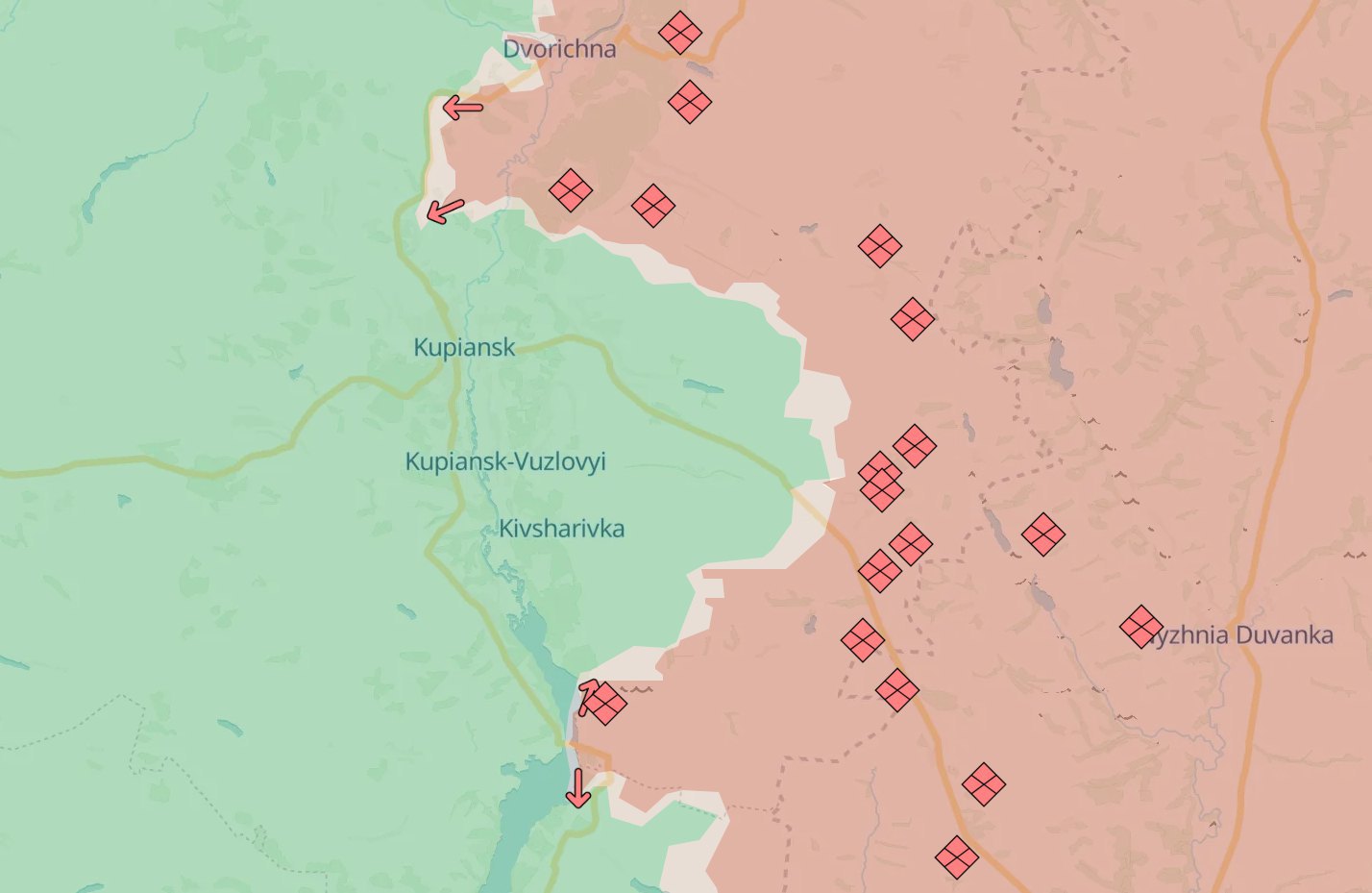

On the Kupyansk direction, the Russian military has been making efforts since late autumn to expand its bridgeheads on the western bank of the Oskil River (there are four of them) and is attempting to extend its zone of control towards the border with Ukraine, while simultaneously aiming to envelop Kupyansk from the north and, if successful, from the northwest. These plans have been significantly hindered by the actions of the Defence Forces in the Kursk and Belgorod Regions, as Russia’s 6th Army has become overstretched along the Borova–Sudzha line and, due to this extended front, lacks the troop numbers necessary to achieve success in any single direction.

In addition to a highly dispersed operational area, the Russian military is facing an acute shortage of manpower and engineering equipment ‒ the latter being a priority target for Ukrainian drones. Since there are currently no functioning crossings over the Oskil, the transfer of tanks and other heavy vehicles to the western bank is impossible, and any attempt to expand the bridgeheads using infantry alone would likely result in severe losses. This situation could shift in Russia’s favour if the North military formation completes its operation in the Kursk and Belgorod Regions and succeeds in establishing a buffer zone of approximately 42 kilometres in the Sumy border area. The alleged “liberation” of Kursk Region was recently reported by the Russian Ministry of Defence; however, the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine promptly refuted this claim.

Throughout the so-called “truce” of 19–20 April, the Russian military attempted to improve its tactical position by moving artillery closer to the front line to target Ukrainian positions from the eastern bank. On both sides of the Oskil, Russian forces began clearing minefields. While they succeeded in clearing several areas east of Synkivka and temporarily occupying them, on the western bank events unfolded according to Ukraine’s scenario: Russian forces were met with mortar fire and attacks by swarms of FPV drones. The Russian military’s most significant achievement during this period was an advance of 150–300 metres in the grey zone across three separate areas.

Once again, the Russians attempted to cross the Oskil River using several BMPs and MT-LBs. However, fighters from the Khortytsya operational-strategic group had a different scenario planned for the holiday period, and the attempted crossing was swiftly repelled under fire from the Defence Forces, effectively ending the Russian operation.

Three Russian IFVs were destroyed while attempting to cross an Oskil river. https://t.co/DGnxEyG50o pic.twitter.com/Px0ZmT0Qp3

— Special Kherson Cat 🐈🇺🇦 (@bayraktar_1love) April 17, 2025

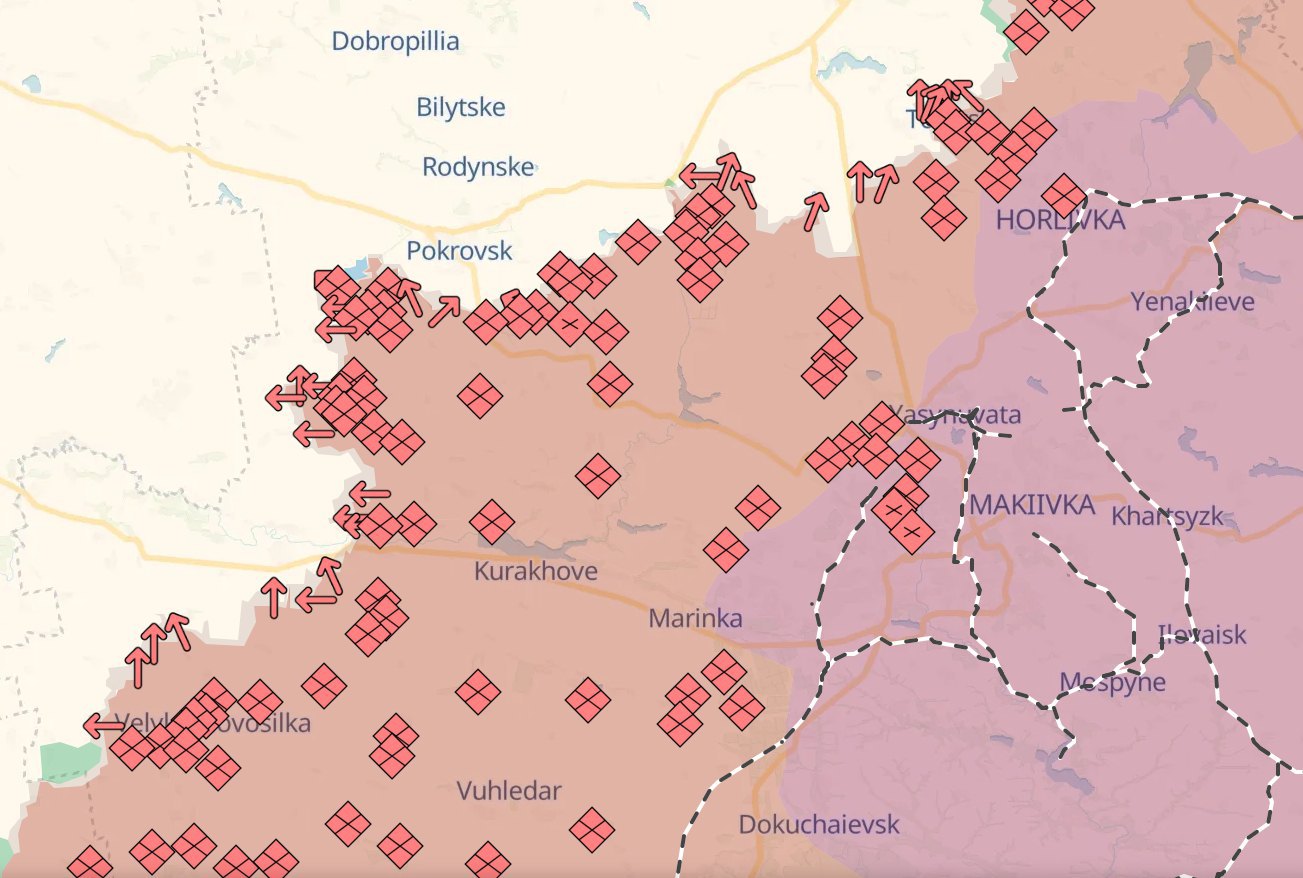

The Pokrovsk direction remains the most tense, although a decrease in the intensity of hostilities has been observed there in recent days.

The Russian military used the “ceasefire” to evacuate wounded personnel from the frontline, rotate units, and reinforce its UAV and electronic warfare capabilities. The latter has significantly altered the air situation ‒ previously, up to 20 April, the Defence Forces maintained air superiority as Russian UAVs were absent. Since 21 April, however, Russian drones have been operating as far as Dobropillya via fibre-optic guidance, which has greatly complicated logistics between Khortytsya and Kramatorsk and Kostyantynivka. As a result, the Dobropillya–Kramatorsk route has been closed for evacuation since 21 April.

Having learned from previous unsuccessful unit rotations, the Defence Forces exploited a similar Russian misstep near the village of Udachne. Soldiers from the Khortytsya operational-strategic group anticipated the arrival of fresh Russian forces and promptly drove them out of the village, advancing nearly two kilometres. On the morning of 22 April, the Russian military attempted to regain the lost ground ‒ but, as one Ukrainian paratrooper reportedly remarked, “if he didn’t take it, he won’t give it back”.

The Russian command Centre continues to strengthen defences in the Pokrovsk–Myrnohrad area and is attempting to prevent Khortytsya from advancing further south. This is significant: the three armies of the Centre group have failed to accomplish their objective, and the plan to capture Pokrovsk remains sealed in a separate classified folder deep within headquarters ‒ unlikely to be reopened soon. Exhausted frontline units are barely holding their positions. On the western flank, near Kotlyarivka, Russian forces are pushing towards the administrative border of Dnipropetrovsk Region, which lies just four kilometres away ‒ though this objective is political rather than military.

The Pokrovsk direction is increasingly becoming a secondary axis, much like the neighbouring Novopavlivka direction. The Centre formation, which was previously defeated by Khortytsya, no longer possesses the capacity to take Pokrovsk or Myrnohrad. The Defence Forces have deployed reinforcements to the area and are gradually pushing the Russian military away from Pokrovsk and surrounding villages, forcing them onto the defensive to maintain control of their current positions. A further withdrawal to Selydove would mark a decisive defeat for the Centre group.

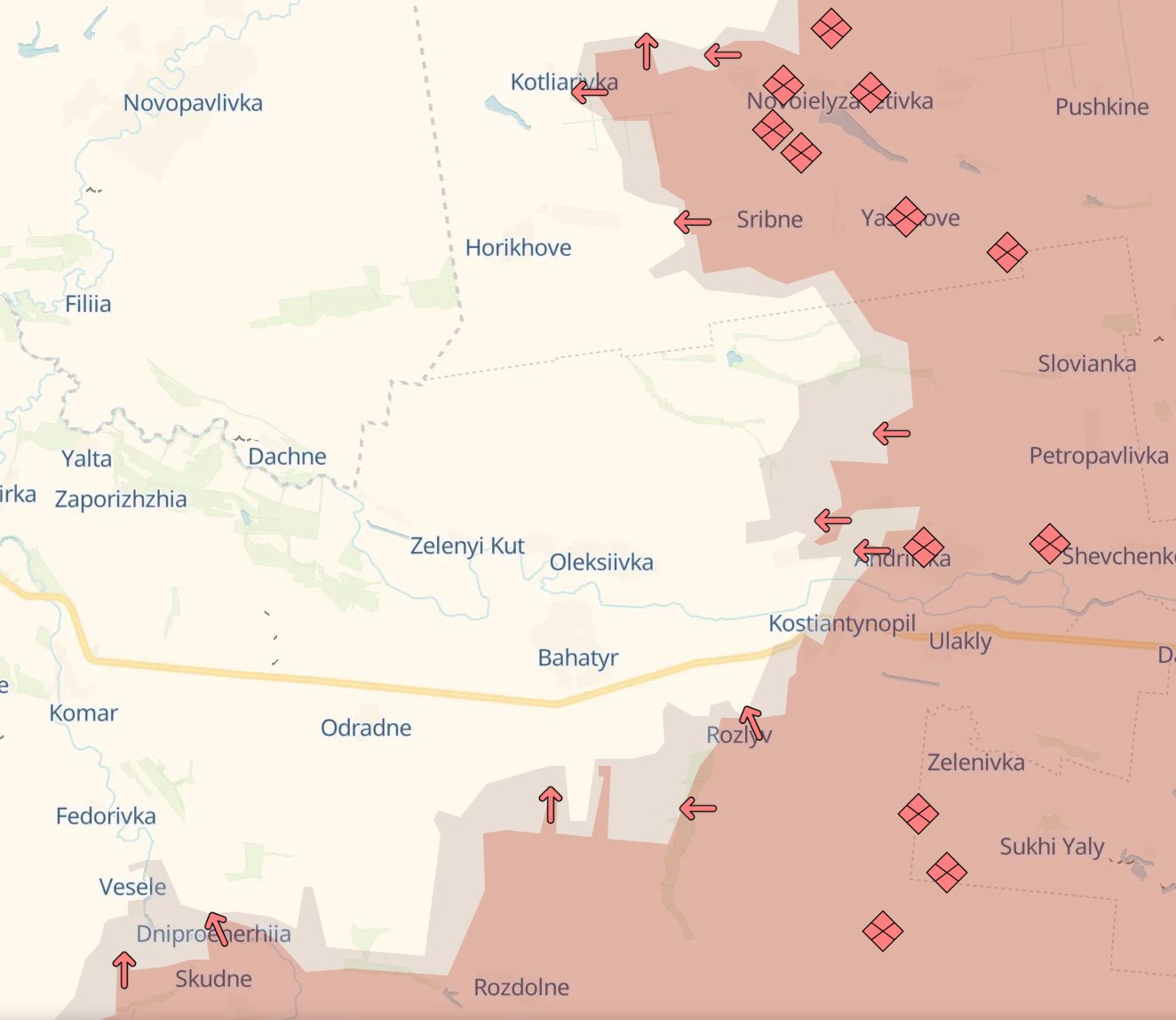

In the Novopavlivka sector, the Russian military ‒ employing two armies in a relatively confined area ‒ is intensifying pressure from Rozlyv, which was captured approximately two weeks ago. It is now pushing towards the Zaporizhzhya–Donetsk highway, southwest of Kostyantynopil, attempting to dislodge the Defence Forces from the area, including from positions near Andriivka and from the southern bank of the Vovcha River, between Kostyantynopil and Bohatyr. Russian assaults on the villages of Shevchenko, Komar and Otradne are ongoing. Although they have lost momentum, attacks are still taking place daily. As in other sectors, the goal remains political rather than military: to reach the administrative border of Dnipropetrovsk Region. The command of Russia’s East formation had hoped to reach this border by 9 May ‒ but will likely have to deliver greetings to President Putin via secure telegram, not with a video from the frontline.

By mid-June, the Russian East military unit, in cooperation with part of the Centre formation, was expected to capture Kostyantynopil, the villages of Odradne and Komar, and push the Khortytsya operational-strategic group beyond the border of Donetsk Region. This would have allowed the South military unit to be reinforced by at least three armies in preparation for an offensive on Slovyansk and Kramatorsk ‒ the planned axis of the main strike in the theatre of operations. It is assumed that the 5th and 36th Armies, currently located near the border with Dnipropetrovsk Region, could be redeployed towards Toretsk and Kramatorsk.

Ukraine’s Defence Forces are determined to prevent this scenario, and Khortytsya will make every effort to ensure it does not materialise.

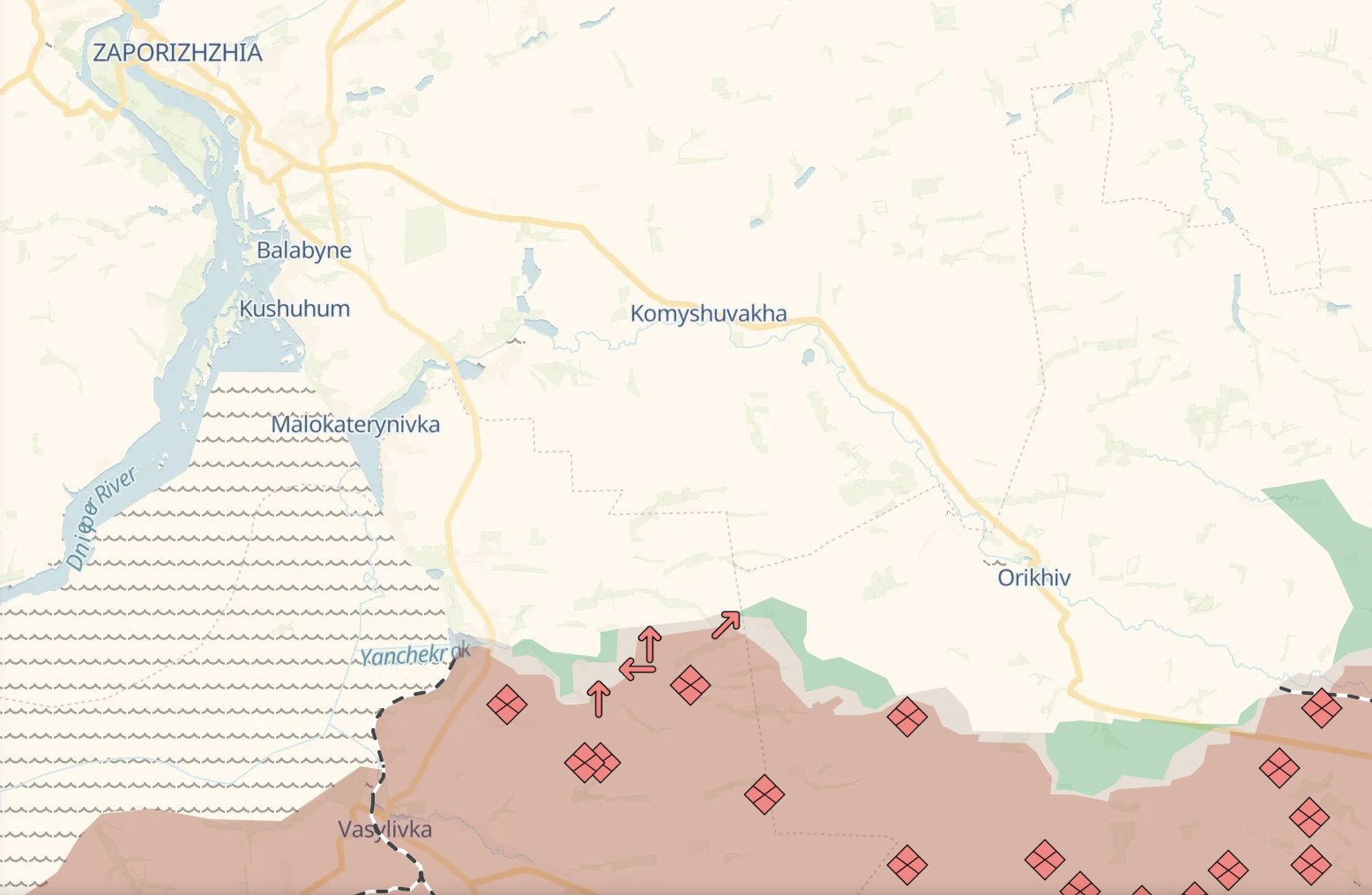

In the Orikhiv sector, over the past two weeks, the Russian Dnepr military unit has conducted two large-scale assaults using combined combat formations ‒ an approach not observed in some time. No fewer than 40 armoured personnel carriers, infantry fighting vehicles and other troop-bearing equipment were involved.

✚ Zaporizhzhia Front ✚

— Astraia Intel (@astraiaintel) April 22, 2025

In the area of responsibility of the 128th, Russian forces attempted to achieve a northwards breakthrough towards Orikhiv but failed to achieve their objectives.

The entire unit—consisting of over 29 enemy armored vehicles and approximately 140… pic.twitter.com/4zOQV4jZqd

Sources from Zaporizhzhya Region reported that this equipment was delivered partly from Rostov Region and partly from Crimea. Some newly trained recruits were deployed as assault troops. This suggests that the Dnepr command had a relatively realistic understanding of its limited offensive potential in Zaporizhzhya Region. It appears that experienced units ‒ notably the 42nd Motorised Rifle Division and the 7th Air Assault Division ‒ were held in reserve. Following orders from the higher command overseeing the theatre, they simulated an offensive and remained in their designated positions.

Both assaults were repelled, with the Russian military suffering heavy losses.

During the recent “truce”, the Russians retrieved the bodies of their soldiers who had been lying along the front line and in the grey zone for several months. They also fortified their positions, attempted demining operations in several locations, and sought to advance in the areas of Stepove and Shcherbaky.

The situation in the area is as follows: the Russian military demonstrated a supposed readiness to mount an offensive on Zaporizhzhya, but in practice limited its efforts to attempting to seize Stepove and Shcherbaky, advancing north of Robotyne, and feigning an attack on Orikhiv. In reality, they lacked the capacity to challenge the heavily fortified Dnepr Defence Forces in this sector.

However, if the Defence Forces were to withdraw even half of their forces and equipment from the area, an attempt at an offensive could not be ruled out. At present, the only major Russian formation operating here is the 58th Army. The zone of operations is unusually narrow for an army ‒ approximately 30 km wide, more typical of a division-level engagement. Within this limited space, at least three Russian divisions are active: the 19th, 42nd and 7th.

Interestingly, the armoured personnel carriers used in these operations were not from the 58th Army’s regular inventory, but sourced from Crimea. The reasons for this remain unclear.

One likely scenario for future developments is the involvement of elements of the Russian Dnepr military unit from Dnipropetrovsk Region. Another possibility is a renewed attempt to force the Dnipro River near Kherson, as the phantom pain of the lost Kherson Region continues to shape Russian military planning.

Instead of a moral, we offer the following key takeaways:

- Neither the 6th nor the 58th Russian Army has sufficient resources to conduct a full-scale offensive. Sources familiar with the situation estimate that current enemy reserves are enough for only a month and a half of active fighting.

- Russia’s information warfare structures will continue to inflate purely tactical actions in the Kupyansk, Orikhiv and Kharkiv directions into narratives of epic scale, in an effort to pin down Ukrainian reserves and divert attention from Slovyansk and Kramatorsk.

- The Russian military command is unlikely to meet not only its 9 May objectives, but also its short-term goals. There is no progress on establishing a “buffer zone”, despite Putin’s personal insistence. The longer Ukrainian troops hold their ground, the more it disrupts the Russian plan to maintain momentum toward Slovyansk and Kramatorsk.

- Without a new wave of mobilisation, Russia cannot achieve the numerical advantage needed for a large-scale offensive. As previously reported in the first part of this series, preparations for mobilisation may already be underway — including the covert purchase of a garment factory and aggressive spring conscription efforts.

- The active presence of Ukrainian Defence Forces in Kursk and Belgorod Regions has forced the Russian military to maintain a substantial grouping there, estimated at 60,000 to 65,000 troops (with some assessments reaching as high as 92,000). This includes the area near Ukraine’s Sumy Region, and ties up manpower that could otherwise be redeployed to the east.

In summary, the first stage of Russia’s offensive to capture the Slovyansk–Kramatorsk agglomeration has begun. The Russian military is targeting the logistics of the Khortytsia air control centre. Enemy air superiority — likely to last from two weeks to a month — is already complicating the delivery of supplies, medical and technical evacuations, unit rotations and overall manoeuvre of troops and equipment.

And what about Ukraine’s Defence Forces?

If Russia does not launch a new mobilisation campaign, Khortytsya is expected to hold the Slovyansk–Kramatorsk line at least until mid-summer 2026. The situation is fluid — even the Carpathian molfars couldn’t offer a certain forecast — but what is clear is that the Russian military has once again failed to meet its deadlines, as has been the case throughout the war.

Meanwhile, Ukraine may yet have a trump card: newly formed army corps. These units offer better command and control, shorter decision-making chains, and faster deployment of large forces — enabling the Defence Forces not only to reinforce problem areas, but also to rapidly form strike groups for counterattacks.