About Zholdak: ‘I think this person should just shut up.’

I don't know how to introduce you: writer, soldier, friend...

I like friend. These aren't empty words — so many years. And now we're also colleagues. I want to thank you for using our content. (Follow this link to read the text versions of the video interviews with Serhiy Zhadan and his colleagues from Radio Khartiya).

Because it's cool and high-quality on Radio Khartiya. But I disagree when you call it a ‘regional project’.

I have never used the word ‘regional’. Because in today's Ukraine, that word means very little. What is Kharkiv? A regional centre? No. In fact, it is the centre of the left bank. I won't even say ‘capital,’ because that word doesn't explain much either. But this city has taken on the administrative and logistical functions of the centre of Luhansk, Donetsk, and Kharkiv regions, and covers Poltava and Dnipropetrovsk regions. It is truly a fortress that now covers half of Ukraine.

So, let me remind readers and viewers: we meet about once every 8-10 months to talk about how we, as a society, are changing during this war. To mark the point where we are.

Almost like a routine check-up at the doctor's (laughs, ed.).

It's the same for me. But before we start diagnosing each other, I want to start with what the whole cultural community is discussing. Recently, at a public event, you told director Andriy Zholdak to fuck off. Was it because of his remark that you can't write?

No, I'm not talking about that remark. Didn't you hear his speech?

I wasn't at the event, although I was invited.

There was a phrase that Ukrainian culture lacks courage.

Seriously?! He said that?

Almost verbatim. A man who hasn't been in this country for 18 years, wasn't here in 2014, wasn't here in 2022, worked in Russia after 2014 — comes to Ukraine, puts on a play about the war and says that Ukrainian culture lacks courage?

I immediately thought of Volodymyr Vakulenko, Vika Amelina, his theatre colleagues – directors and actors who are fighting, many of whom have died, those who have returned after being wounded and continue to work.

And then a touring actor appears, for whom these 18 years have simply been cut out: he has remained in the past and continues to shock. He wonders whether our culture has ‘courage’. It seems to me that this person should just shut up.

He has the opportunity to work – let him work. He hasn't broken the law – no one is stopping him. But he has no moral right to pass judgement on an entire culture with which he has had no connection for 18 years.

Obviously, I could have said, ‘Mr. Andriy, you have no moral right to judge Ukrainian culture.’ I said it more succinctly.

You did the right thing! If I had been there, I would have reacted the same way. I asked just now because I heard ‘you can't write.’

That's not an accurate phrase. It didn't mean ‘the words don't come,’ but ‘I can't write.’ But I do publish books. Arabesques has been published and translated into more than 20 languages. The thesis of a person who is out of context does not understand what is happening. He arrived and started teaching us.

It's kind of like the ‘good Russians’ who say that they ‘suffer too’.

I don't want to label them ‘good Russians’ — it sounds like a judgement. But tact and ethics are necessary before touching on painful topics. Because today it is no longer the culture of 2010 or even after the Orange Revolution. Everything has changed. We have changed.

But I'm not talking about him, it's just a parallel. But let's talk about these changes from a cultural perspective. At the beginning of the war, you said that it is important for a writer to absorb and observe in order to later produce a large form. A year and a half or two years ago, you said that ‘this rain will last a long time,’ so we need to act simultaneously. You mobilised at that very moment and joined the Khartiya, which you had previously helped as a volunteer.

Now, in one of your latest interviews, you say that you simply don't have the time for a great novel, because you need to literally immerse yourself in the ‘great form.’ You are now writing essays and short forms on the go — and that's okay. Many representatives of ‘great’ (high) literature say the same thing.

But I am concerned about something else: the results of this war in Western literature may be summed up by the ‘good Russians’ themselves. They have the time and inspiration, they are ‘suffering too’. How can we prevent this threat?

They are already writing and producing feature films and documentaries, they are being given platforms. The world has its distance from our events and its own perspective.

They will invite, for example, a director from Russia, Kirill Serebrennikov, who will give his point of view. According to Western experts, it ‘has a right to exist.’ Plus, there will be a series of books and films by foreign authors about us — based on our material.

This is already happening. And it is not necessarily something unacceptable. For example, Howard Buffett's exhibition at Ukrzaliznytsya features very powerful, honest, and insightful photographs. Although the man came as a tourist, he approached the subject with empathy — and you can feel it.

You know, your speech after the interview with Ai Weiwei really triggered me. For seven minutes, you said that he is on our side and supports us, that he knows what dictatorship and communist China are like, but still – it's a different language, a different perspective.

At the beginning of the war, you said: ‘I've worked with words my whole life, but it turns out that not everything can be expressed in words.’

So, maybe in 3.5 years we haven't found the right words to explain to the world that ‘not everything is so clear-cut’?

It is wrong to blame ourselves now. We weren't sitting at our desks editing texts at that time — we had other things to do. Even those who weren't in the army: 3.5 years under air raid sirens is about survival, not about searching for words.

The very phrase ‘citizen of the world’ doesn't explain much either. The world includes Iran, Canada, North and South Korea. Which ‘world’ are you a citizen of? After the fall of the Berlin Wall, it seemed that the movement towards shared values was irreversible.

It turned out to be the opposite: revanchism is returning. So ‘citizen of the world’ is more about an unwillingness to articulate one's political position.

When I say ‘we couldn't,’ I'm not talking about artists, but about us as a society and as a government. We are not being heard — it is obvious that someone does not want to hear us, yes. But perhaps we should change our articulation and messages: 2022 was one thing, 2023 was another, and now 2025 is coming to an end.

I agree. The atmosphere is changing, the world situation is changing. Three years ago, there was no war between Israel and Palestine — now there is. Accordingly, the emphasis and attention are shifting.

The image of a victim, however justified, cannot be exploited forever. Something has to change. Now is the time to show Ukraine as a strong society that has survived. Accordingly, it already has something to offer.

I like the initiative to sell weapons: it is not about profit, but about capability. You thought we would last ‘two or three days,’ but we are already more than half self-sufficient in drones and missiles — and we are offering cooperation. It is about strength and dignity.

After all, it all started with dignity. When we forget about it, we are blamed for everything. When we remember, the conversation is completely different.

This is basic. This is what the world did not understand and what Russia ‘stumbled’ upon. Well, we will talk about this in a local context a little later. For now, I want to close the topic with the West.

How to proceed in a substantive manner? Not just correcting old approaches, but building new ones so that they really have an effect? It's no coincidence that I mentioned the ‘good Russians’. Let's be honest: from our perspective, Remarque is a typical ‘good Russian’ who wrote about ordinary German ‘our boys’ who were sent to their deaths.

The matrix of the 20th century does not adequately explain our war. Comparisons with the First World War, Remarque, Céline, Apollinaire — do not work literally. We have a different reality: the alternative is our destruction.

Here I agree: the Russians will definitely not repent. We agree that neither of us believes in a hypothetical Willy Brandt who, in 25 years, will bow his head before the monument to those who died in the Warsaw Ghetto, that is, in Bucha.

The trouble is that geographically, the Russians are not going anywhere. And we will have to somehow explain why we want to cancel them and have nothing to do with them.

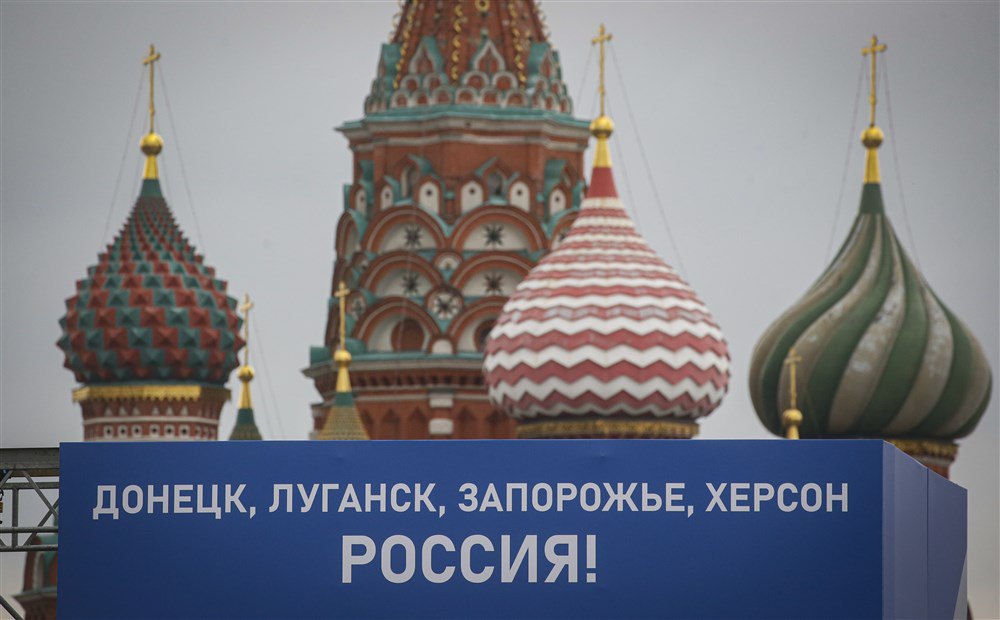

What's more, they have occupied part of our territory. Even if there is a truce tomorrow, sane Ukrainian citizens will not call Luhansk ‘Russia.’ They will still understand that this is our territory.

It's not about ‘I don't recognise this territory as Russian, so I'm ready to grab my sabre and charge into battle.’ It's about a common understanding at the societal level.

‘Political projects like those that existed before 2014 will no longer work.’

Let's now talk about what we gathered for — changes in society. You are a writer and opinion leader, you serve in the army, you are actively involved in journalism, so you have different perspectives. I am particularly interested in the transformations of the younger generation. What has become the anthem of the ‘cardboard’ protests, why do young people sing along most loudly when ‘Zhadan i Sobaky’ perform in the metro? It's a phrase from the song “Avtozak”: ‘Why the fuck do I need a system that works against me?’

I'll tell you that the military is also reacting.

Well, because this phrase is about dignity. That's where we started. But look, it's gotten worse lately, I think.

Wherever there are signs of political life, there is also public discontent. In the first two or three years of full-scale war, there was a conditional, unspoken social contract to work together. But now that society sees that political life in Ukraine exists somewhere, it is obvious that it is becoming a subject of attention and sensitivity.

And Ukrainian society, for whom this whole story began with the Maydan, continues to keep the issue open. Regardless of what has changed — several governments, several prime ministers, two presidents — for many people, this story is still relevant. Because it is about dignity and justice.

What are the biggest differences in the mood of Ukrainians that you see now?

We travelled all over Ukraine with Khartiya: about 20,000 people, mostly young people, attended our events. What do I see first and foremost? Total support for the defence forces, and therefore for the state.

Because, you know, you can think different things right now. You talk about young people who took to the streets to protest. Some talk about young people who continue to watch Russian YouTube and TikTok. There are different points of view on what the younger generation is like.

But I see just total support for their country. And I'm not straying from your question — it seems to me that this is the defining thing, the prerogative: first and foremost, to preserve the country, to hold the borders.

Young people are very proactive, and those who stayed here are showing this awareness.

I understand that the word ‘consciousness’ echoes the 1990s — ‘conscious Ukrainian’ and so on. Back then, our enemies turned it into an anti-meme. But despite this, this consciousness exists and is very widespread.

Of course, I am not idealising; we are at a difficult point, one where it is hard to maintain balance. Right now, we are like tightrope walkers: we have to make an effort not to fall.

Because we don't know how long it will last. Phrases about it being a ‘marathon’ no longer work.

Only we, the adults, talk about how long it will last. Fifteen- to seventeen-year-olds are just living their lives — and they have the right to do so. For them, their entire lives have been spent in wartime (if we count from 2014). Plus, socialisation has been disrupted by the pandemic and full-scale invasion: schools and universities are sometimes offline, sometimes online, and on the left bank, often only remotely.

Now I will quote you again. This time from Radio Promin: ‘Different cultural codes are a real headache.’ The song is about relationships, but it could also be about generations.

If there are no common cultural codes, how can they be built and changed? Especially when we talk about young people: most of them are abroad now, and sooner or later some will return. Not all of them, but those who do return will have different codes.

Listen, I understand what you're talking about. I think there really is a huge gap between generations. Under normal circumstances, this would be a huge social problem — a kind of time bomb. But I think that in our situation, it's not so bad.

Why? Because this gap arose because reality itself broke down. We all found ourselves in a different reality. Hundreds of thousands of children and teenagers who had never before thought about which culture or state they belonged to were suddenly confronted with this in a vitally important way.

When a child sees that their father or mother has gone to war, these issues cease to be just a topic for kitchen table conversations. It becomes a serious choice. For many teenagers, this is the first time they have to choose their political position — a choice that, under normal circumstances, is made by adults.

Yes, it is painful and traumatic, and it breaks some people. But for many, the opposite is true — it becomes easier after making a decision. And many discover Ukrainian music, culture, history, church, and politics precisely because of this extreme situation of threat.

We have a generation for whom the textbook is life. They are rebuilding the walls of our continuity almost ‘out of thin air.’ They don't remember the 90s or the 2000s — and that's okay.

I think the problem is not that they don't know what happened in the 90s and 2000s, but what happened even earlier. You know, I remember Alla Horska's exhibition last year in Kyiv. I was struck by the fact that most of the visitors were young people. Of course, almost all of them were Ukrainian-speaking. I couldn't have imagined such a thing before.

Okay, they came to see Horska more as an artist, but in addition to her mosaic from Mariupol, there was also the ‘Bykivnya’ hall. I spent a lot of time there and watched closely as people who came to see sketches for theatre productions and paintings left ‘Bykivnya’ completely changed. Of course, I do not diminish the role of Horska as an artist, but for me, the ‘Bykivnya’ hall was the main attraction there.

It is important to know everything: Ivasyuk, Stus, the early Braty Hadiukiny, the dissident movement, and the OUN. Because, in fact, this is the whole world. And there is simply no place for this narrow specialisation here. Narrow specialisation does not work for a citizen — a broad perspective is needed.

Let's try to think about what this could lead to. For context, I'll tell you a story that our viewers definitely don't know.

Initially, the Khartiya festival, which you held at the end of the summer, was planned to take place in Podil. Everything had even been agreed upon. But then the authorities quietly banned it there. Because it's next to Mohyla Academy.

Well, I can't comment on that.

I'm not asking you to comment. Let me finish. So, it's next to Mohyla Academy. It would seem: what's the big deal? I didn't understand right away. It turns out that someone calculated that there were a lot of Mohyla Academy students at the ‘cardboard protest’ and if they gather again for a music festival, it's unclear what they'll decide to do and where they'll all go. The logic is completely abnormal. More precisely, there is no logic here. But, honestly, such suspicions on the part of the authorities scare me. They just scare me.

This is more like something from 2004. I mean, when there was a government that was not accepted and not understood, that people opposed, and there was a part of society that opposed it.

I think it's more about the government's unwillingness to listen to society. The government as such, in principle.

Today's government — in certain respects, yes. I completely agree with that. I'm just saying that the very model of this misunderstanding — on the one hand, the government, and on the other, society — is of a completely different nature.

It seems to me that we are currently undergoing a major transformation. And this transformation is happening at all levels: at the level of the probable future of political life, which will resume sooner or later.

At some point, let's say, martial law will be lifted and elections will be announced. And someone will run in these elections. Obviously, in addition to the old parties, many new ones will appear.

And I have a very clear feeling that their structure will not repeat the political projects of 2014. Because, it seems to me, they will no longer work now. This is because, in particular, the demands of society are completely different.

It will be a parliament of military personnel and volunteers.

Listen, what do you mean when you say ‘parliament of military personnel’? Remember the 2014 elections, when there was a combat commander in every five candidates. And suddenly there were a lot of military personnel in the Rada. But could that parliament be called a parliament of military personnel? Definitely not.

Some may try to ‘play the military card’ in the elections by involving well-known combat commanders. But this is unlikely to work: our army is outside politics, and involving it in political processes is dangerous.

It is much more likely that new political forces without a military base will emerge. People with military experience can apply it in political activities, but this does not make the army a political platform.

There are people in the army with their own ideological positions, and political projects may arise on this basis. The main thing is that the army itself will remain outside politics.

When we arranged this meeting, you said you didn't want to talk about politics. And, honestly, that scared me a little.

Why?

Because I thought: what if you're thinking about going into politics too? Please tell me you're not planning to do that.

No, I'm not.

Thank God!

I want to go back to what I was doing before 2022: education, culture, working with communities, Ukrainisation of the Left Bank. And yes, after my service, I am ready to do this because I know what needs to be done and with whom. My military experience has taught me to distinguish between who is worth working with and who is not.

But what if, for example, General Zaluzhnyy or General Budanov create their own party and say, ‘Serhiy, our party needs you to work on the Ukrainisation of the Left Bank of Ukraine, education, and culture’?

My attitude towards state institutions changed after 2014. It became clear then that supporting institutions is a priority, even if the artistic community previously believed that the state should be criticised or ridiculed. Now I see the point of it and understand the necessity.

I know exactly what I will lose by going into politics. And I can see very clearly that I will not gain any opportunities for my work. Therefore, I rationally assess my opportunities.

Let's summarise the political topic. The most important thing for me is that the future parliament is formed not on the principle of ‘pixel or no pixel’, but on the quality of people. That there are competent and responsible people there — both civilians and those with military experience.

At the same time, there will always be a part that will vote for the conditional OPZZh (Opposition Platform — For Life). This is probably the greatest danger.

You understand that we are no longer talking about the configuration of parties, but about specific people who can enter this niche and use the narratives of reconciliation, forgiveness, and ‘rolling back.’ Part of society is ready for this — and that is a fact.

So, the question is: what else needs to happen for this to change?

I think we have already passed the point of no return. Yes, society cannot be unanimous. Even in the elections that Hitler won, the victory was actually within a margin of error. In fact, it was almost 50/50. So, yesterday there were 50% of Germans who opposed Nazism, and a year later they were gone?

I talk to a lot of people from different regions — it's part of my job. And my feeling is that the models of political, economic, social and cultural life have already changed. The point of no return has been passed. We just can't see it right now because of the war.

We are living in ‘twilight,’ when the lights are off. But after victory, they will turn on — and we will see a completely different picture. It will not be like it was before the war. Some things will remain, but many new things will appear.

This does not mean that it will become easier. On the contrary, it will be difficult, because in many cases we will find ourselves unprepared. Everyone subconsciously expects the end of the war to be the end of stress. But that will not be the case, obviously. Yes, it will become easier, warmer. However, many things will gradually transform — they will not disappear, they will simply be perceived differently.

And don't forget what is happening every day? Every day, those who did not vote in the 2019 elections are growing up. At that time, they actively supported Servant of the People — it was their ‘against all’ protest force against the old system. But today, I am not sure that they still perceive this party as their own.

They may have a certain attitude towards the president. He is very specific in our country: to a certain extent, he falls outside the political system, while Servant of the People itself has never been a real party. It is not a political force, and certainly not a leading one. It is rather a group of people gathered around one name that united them.

In this sense, everything is changing. And the question arises: who will take these young people under their wing, whom will they consider their politicians?

The most predictable thing is that protecting their territory and country will be key for them. That is, the military.

But this will continue only as long as their parents are at the front. When they return, they will say: ‘I support this local politician, these young leaders, this new political force.’ Well, there will be no political party called ‘Armed Forces of Ukraine’.

There will not be one, there will be several. And not ‘Armed Forces’, but their individual representatives.

Perhaps you are right. And here it is difficult to say... It seems to me that there will be a great demand for this issue of justice. At the same time, this opens up a wide space for populism, but also for real management decisions that will show a breakthrough.

I doubt that young voters will support the parties of 2014 — for them, these are already ‘dinosaurs’ who speak the language of the past and offer no answers to the challenges of the future. The younger generation will vote for those who can speak their language and provide solutions that are relevant to post-war Ukraine.

‘Our hope is being shaken, we are being deprived of it, but it is a resource no less important than weapons, bomb shelters or the economy.’

Since we are talking about the future... Tell me, how has your idea of victory changed? What does victory mean for Serhiy Zhadan in 2025?

That's a difficult question... Obviously, if Ukraine can preserve its statehood, secure the support of the world and guarantees for its security, that can be considered a victory. I understand that many people will now take offence and turn off the channel.

Because we don't mention the 1991 borders.

We remember them, but we don't focus on them. I have already said this: it is unlikely that the majority of Ukrainian society will accept that part of its territory has been lost. I am convinced that this will not happen.

The lack of complete justice may determine the mood of part of society. This is not very good because it can cause disappointment and depression. But it is important to focus on what we have left: our state, our territories, our citizens and our children — these are our resources.

We can try to build a prosperous state in the territory we control.

First, we must protect these territories. Second, we must remember that the territories that are not currently under our control still belong to us and we cannot give them up. History has already shown that we must learn patience, endurance and perseverance.

The only question is whether the people who live there will wait for this.

Listen, this is an important question, no doubt. But I don't think Ukrainians today should ask anyone's permission to take back what is theirs.

Of course!

This is a question of dignity. We are not talking about someone else's property, we are talking about our own. That is what justice is all about.

Take Crimea, for example. In 2015, more than 800,000 Russian citizens arrived there, who were given housing allowances, jobs, and resettled from various places. Some of these people — military families — will leave, while others will stay. They will have Russian passports and, although they will not vote, they will create the appropriate climate.

You can look at it this way. Or you can remember Crimea in the 1980s. In 1985, before Gorbachev came to power and perestroika began, who could have imagined that Soviet Crimea would once again become home to the Crimean Tatars? Almost no one. Only visionaries like Mr. Dzhemilev believed in it and took concrete steps to achieve it.

What I am saying is that many things seem impossible at the moment, but everything can change quickly. In fact, drawing historical parallels is a thankless task: they are inaccurate, subjective and often far-fetched.

But just look at the major conflicts of the last 50 years: the Balkans, the Caucasus. Who would have thought a few years ago that everything would unfold this way?

And you know, that's a very good way to end the conversation — you've given us hope. I'll quote again, this time from Metro: ‘This is the metro that gives hope. Somewhere deep in the station, my heart is beating.’ Simple hope is sorely lacking right now.

Our hope is being shaken, we are being deprived of it, but it is a resource no less important than weapons, bomb shelters or the economy. When we lose ourselves emotionally, we become helpless.

I look at Kharkiv — there are over a million people there again who are returning and want to live. I imagine that as soon as the war or its hot phase ends, a new history will begin for Kharkiv. It may not necessarily be a good one — we are already paying a high price for it: lives, cities, the economy. But the city remains, the people remain — and there is a chance. And we must take advantage of this chance.

I think these are completely different opportunities and a completely different story for Kharkiv.

For other cities — their own, but also new. It is important to cherish hope and remind ourselves of it. Thank you for doing that today — for us, for the viewers, for the listeners. I hope that next time we will be talking about victory.

You know, when the election process begins, I would like to talk to you about it myself, to comment on it. I have an idea.

Well, then you will be interviewing me, not me you.

Agreed!