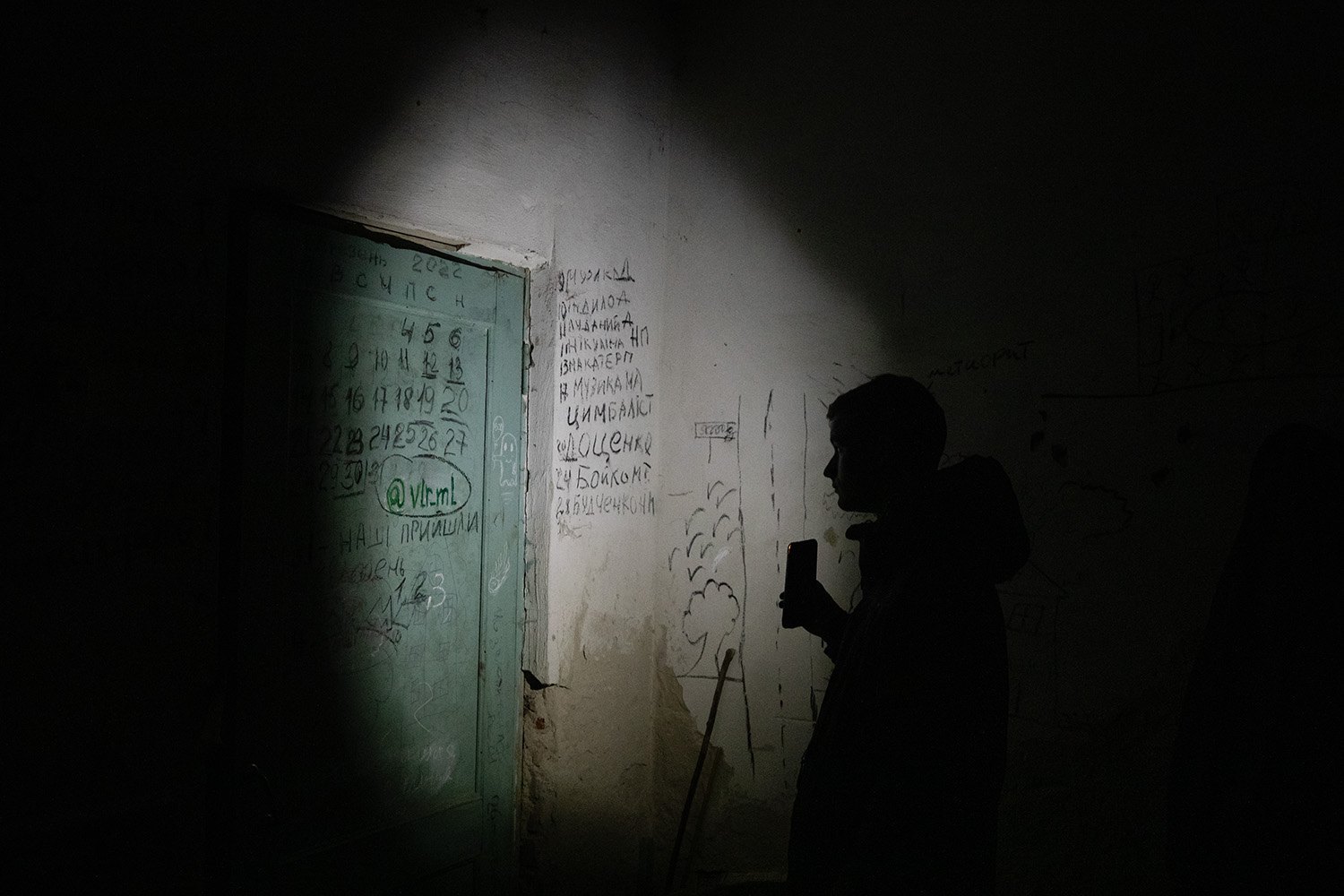

Following large-scale counter-offensives in the Kharkiv and Kherson Regions in 2022, reports of the liberation of occupied territories were accompanied by horrific images from places of detention. These locations, where occupiers had imprisoned and tortured civilians, revealed evidence of both men and women being subjected to sexual violence and sexualised torture.

Sexual violence is often associated with feelings of guilt, shame, and stigma, making it difficult for victims, as well as law enforcement agencies and human rights defenders, to address. Aware of this, the Russian military deliberately resorts to these prohibited acts as a means of collective punishment and intimidation in the occupied territories.

As of 3 March 2025, the Office of the Prosecutor General has recorded 344 cases of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), LB.ua reported. Most cases involved women (220), but among the victims were also 124 men and 17 minors (girls and boys). The highest number of incidents occurred in Kherson Region (110 cases), followed by Donetsk (81), Kyiv (60), Kharkiv (40), Zaporizhzhya (23), Mykolayiv (10), Chernihiv (8), Luhansk (8), Sumy (3), and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (1).

The International Partnership for Human Rights team, in collaboration with Truth Hounds, Bluebird, and Jurfem, has been documenting cases of conflict-related sexualised violence in Kharkiv, Kherson, and Mykolayiv Regions for the past two years.

Currently, the IPHR legal team is analysing cases of sexualised torture in Kherson Region to submit materials to the International Criminal Court.

80% of respondents reported CRSV

Anastasiya Donets, Team Lead of the Ukrainian legal team at the International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR), said that the IPHR field team interviewed 70 victims who had been held at the Kherson temporary detention centre.

“The majority of victims – eighty per cent – reported some form of sexual violence. The forms of sexual violence used by Russian forces do not always fall under the traditional understanding of sexual violence, such as rape or sexual slavery,” she commented.

According to IPHR, threats of rape against victims and their relatives were common forms of sexual violence.

“I was punched and kicked in the chest, stomach, and head, and stunned with a stun gun on my back and arms. They threatened that if I did not tell them where the Ukrainian military were, they would kill me, electrocute my genitals, or put me on a bottle,” reads an excerpt from the testimony of a victim held in a temporary detention facility.

Forced nudity, often accompanied by threats, humiliating comments, blows, and electric shocks to the genitals, as well as threats of castration or genital mutilation – these forms of torture are frequently encountered by field documenters interviewing civilians captured by Russia in Kherson and other regions.

“Once, during an interrogation, they put me on a chair, taped my hands to the chair arms, and taped my legs so that I couldn’t move. They connected terminals to my finger and earlobe and shocked me with electricity. The second time, they put terminals on my nipples, which was much more painful. They also touched my genitals once,” reads another excerpt from a victim’s testimony.

However, some methods of CRSV were encountered by documenters only at the Kherson temporary detention centre (ITT), including forced witnessing of rape. As Anastasiya Donets explained, field researchers interviewed detainees who regularly heard other prisoners being raped in the corridor outside their cells. The Russians used such methods not only to break resistance and humiliate the victims but also as a means of collective intimidation and punishment for all detainees in the ITT.

“One man – we heard it – was raped with a bottle. The one who was raped was shouting: ‘Guys, don’t, don’t,’ and then there was a scream,” reads an excerpt from the testimony of a victim held in a temporary detention facility.

No court practice

All of these acts can be classified as war crimes and crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), which Ukraine ratified in August 2024. Currently, international jurisprudence characterises these acts as torture, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

According to Anastasiya Donets, this approach has several drawbacks. Firstly, it creates a discrepancy between how sexualised violence is addressed in the criminal justice system and how it is perceived and experienced by victims.

Secondly, this classification prevents the prosecution of this specific type of violence as sexual violence. As a result, the scale of sexual crimes – as well as their perpetrators, victims, and witnesses – remains outside the focus of the criminal justice system and the international community.

Thirdly, inadequate or incomplete classifications that fail to recognise the sexual dimension of these crimes result in insufficient, inappropriate, or even non-existent remedies, as well as limited sources of support and recovery for victims.

“The challenge in classifying sexualised torture is that it is not designated as a separate category of crime in either the Rome Statute or the Criminal Code of Ukraine,” Donets explains. “Instead, the Rome Statute uses a broad term – ‘other forms of sexual violence’– comparable in severity to rape or sexual slavery. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian Criminal Code refers to ‘sexual violence,’ which can include any act other than rape, which is classified separately. Today, there is virtually no international judicial practice of prosecuting sexualised violence as an act constituting ‘other forms of sexual violence’.”

“The practice of classifying sexualised torture solely as torture, inhuman, or degrading treatment fails to recognise the nature of these crimes or the unique stigma attached to them,” she adds.

This is why the strategic goal of IPHR’s work in this area is to ensure that not only documented cases of rape but also threats of rape, forced witnessing of rape, forced nudity, and sexualised torture – collectively referred to as sexualised violence – are recognised as such.

“The widespread, systematic sexualised violence committed by Russian occupation forces against the Ukrainian civilian population must be prosecuted as sexual violence. Such classification is crucial not only for holding perpetrators accountable but also for establishing the truth about Russia’s war against Ukraine and helping affected communities understand and overcome its consequences,”Donets concludes.

Victim-centred approach: working in a team with lawyers and psychologists

Recognising the complexity of documenting this type of crime, colleagues from the International Partnership for Human Rights, Truth Hounds, Bluebird, and Jurfem have joined forces not only to collect evidence of Russian war crimes but also to make the process as least traumatic as possible for victims.

This is a unique project, says Oksana Pokalchuk, co-executive director of Truth Hounds. “Since field researchers work directly in the de-occupied territories alongside lawyers and psychologists, this enables them to establish a warm and trusting relationship with victims.”

“Such documentation allows us not only to listen, record, and leave but also to truly hear requests for help. While we do not provide direct assistance – such as humanitarian or financial aid – we assess needs and refer individuals to the appropriate funds and institutions on a case-by-case basis. Thanks to the presence of psychologists, our witnesses feel more confident during or after the interview, as they have had a session with specialists beforehand. Following documentation, Jurfem lawyers provide legal consultations and can accompany victims throughout criminal proceedings. This is only part of the process, as working with cases of sexualised violence requires time and careful steps,”explains Pokalchuk.

She notes that society is not yet fully prepared to talk about or listen to discussions on sexualised crimes. Words such as “sex,” “rape,” “humiliation,” and “captivity” provoke fear and a desire to distance oneself from the information. The role of organisations working on CRSV (conflict-related sexual violence) is not to impose these topics but to bring them into public discourse alongside other forms of torture.

“We need to address this issue in a way that ensures public perception of survivors of CRSV is the same as that of other victims of torture. Those who have experienced this should not feel discriminated against or alienated. We are all learning to live in a new society and adapt to new challenges. The key is to be more sensitive to one another,” she believes.

The need for the existence of the CRSV in the legislative field

The issue of the absence of a specific article addressing CRSV is also highlighted by Nataliya Radionova, a lawyer from the Jurfem support line. She explains that most of these crimes fall under the broad and impersonal classification of war crimes under Article 438 of the Criminal Code and are recorded in investigation registers as acts of cruel treatment of civilians or other offences.

“For victims, this creates challenges in proving that they are survivors of CRSV, especially when applying to funds or commissions for compensation, benefits, and guarantees. Not everyone is ready to report sexual violence when initially contacting law enforcement, so these cases are often recorded under Article 438 in the URPTI. As a result, victims require additional confirmation and proof of their status,”Natalia explains.

She emphasises that CRSV is a distinct crime and a component of genocide. When it is not acknowledged in the legislative field, we unintentionally diminish the suffering of survivors and, at the same time, fail to recognise it as a deliberate and illegal method of warfare systematically employed by the occupiers.

***

This material was prepared with the support of the Institute for War & Peace Reporting (IWPR).