New Zealand is an exceptionally musical country. With a population of five million, it boasts more than a hundred orchestras, and eighty per cent of residents attend at least one concert each year. It was musician and pianist Flavio Villani who was the first local artist to respond to the war in Ukraine. In his concert improvisation at the end of February 2022, the Ukrainian anthem emerged triumphantly from the turmoil of notes, bringing tears to the eyes of the grateful audience.

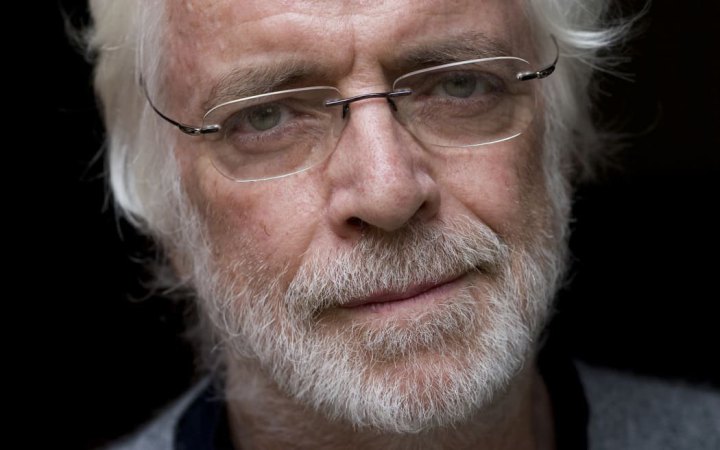

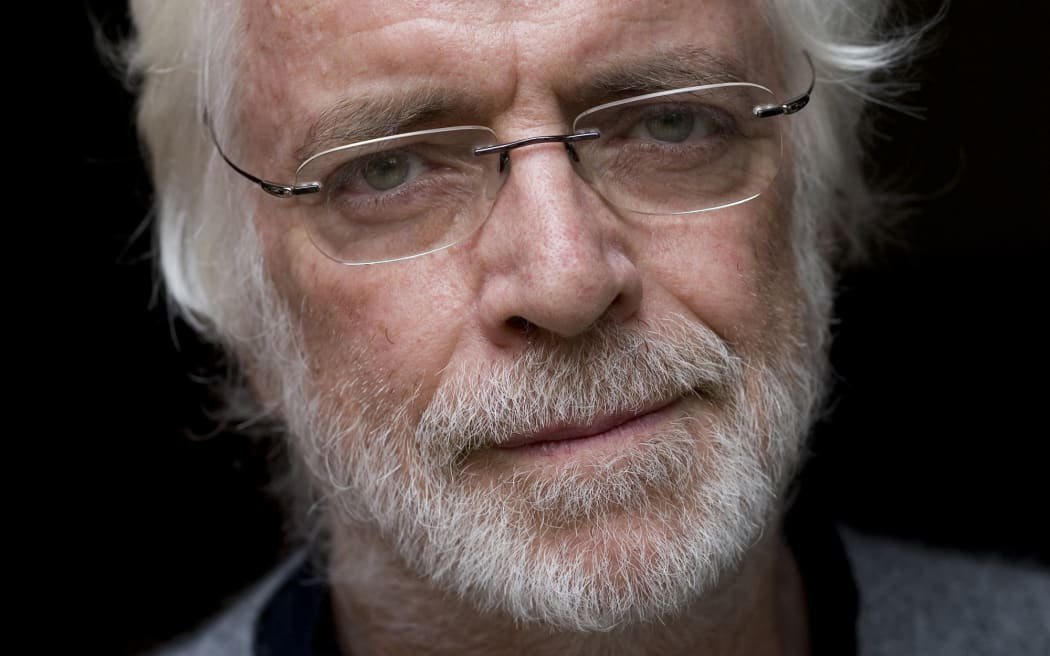

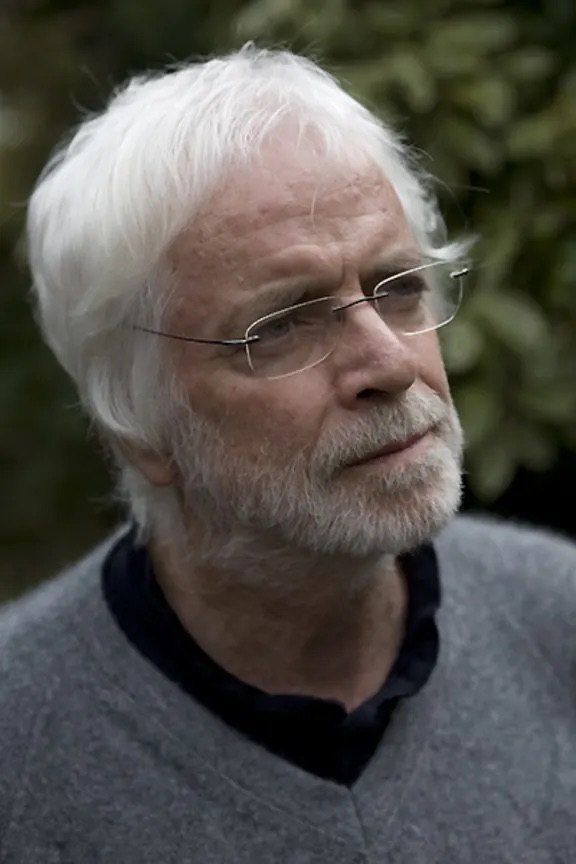

Eighty-year-old Ross Harris gained recognition in the music world forty years ago when he wrote the first opera in the Māori language and has since composed more than two hundred musical works. Some of them, in particular, are imbued with the theme of war, as the composer seeks to feel and depict its horrific essence. Harris’s previous symphonies addressed New Zealand’s role in the First World War (Symphony No. 2) and the tragedy of the Second World War, along with the moral responsibility it entailed (Symphony No. 5). On the eve of the premiere, CultHub asked the composer how he perceived the Russian–Ukrainian war and what thoughts and emotions he sought to convey to the listener.

“When Russia launched its aggressive attack on Ukraine in 2022, I wanted to express my horror at this invasion by writing a symphonic work. The new war in Europe was a return to the horrors of the wars of the previous century. My work begins with deep sadness. Slow, mournful melodies performed by strings accompany three percussion instruments, which eventually intrude on the strings’ music. The destruction of music by military strikes may symbolise the ongoing destruction of Ukrainian cities and villages. In fact, I am following reality. The work ends with a long, slow melody whose relative simplicity symbolises hope and possibility, but not yet a solution or resolution.”

Ross Harris noted that he is delighted that Ukrainians will be able to hear his symphony: “This music embodies support for your country, and I think that should be felt.”

The conversation turned to music as a component of culture in times of military conflict. According to the composer, the idea of writing a symphony that supports Ukraine in this war has a political dimension but remains, in essence, an abstract artistic expression. Harris, who does not question the relationship between artistic self-expression and civic responsibility, never perceives his works as having overt political overtones — partly because they have little direct influence on the society in which he lives, apart from expressing the liberal ideas he believes in.

“Writing a symphony that supports Ukraine in this conflict has a political dimension, but as an artistic expression it is an abstract form. In fact, I have never questioned the relationship between artistic expression and civic responsibility. I never perceive my works as having a civic function, partly because they have almost no influence on the society in which I live. When I use words or obvious themes, I try to express the liberal ideas I believe in. Incidentally, most of my knowledge about Ukraine comes from the works of Professor Timothy Snyder. His lectures at Yale University on the history of Ukraine are extremely informative, and I am sincerely and deeply interested in the fate of a country with such a unique background.”

I asked about the attitude towards the performance of works by Russian composers. In New Zealand, compositions by Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, Glinka and others are traditionally included in the programmes of most local symphony orchestras, and the Royal New Zealand Ballet has already begun its season of The Nutcracker ahead of Christmas. This is a long-standing tradition that, regrettably, has not been altered by Russia’s aggression.

In fact, as Ross Harris observed: “I hope that composers such as Shostakovich, whose works are powerful human symbols opposing the cruelty of their country, will not be banned from performance in other nations, because they transcend borders and should reach people of all cultures.”

This opinion is quite common in New Zealand’s artistic circles. It makes it all the more important to find opportunities — even here, in the country furthest from Ukraine — to speak about today’s Russia as a cruel aggressor, child abductor and ruthless invader, far removed from high art. This is precisely the task undertaken by the local Ukrainian community and the Ukrainian Embassy in Australia and New Zealand.

The concert will feature the world premiere of Ross Harris’s Symphony No. 8 for strings and percussion, described in the programme as a response to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, preceding Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9.

“The combination of my Eighth Symphony with Beethoven’s Ninth is a happy coincidence, not chosen by me,” Ross Harris noted. “My work is full of unanswered questions, while Beethoven’s is a monument to the Enlightenment, full of hope. It’s a beautiful combination — no doubt about it! I would even call it optimistic.”