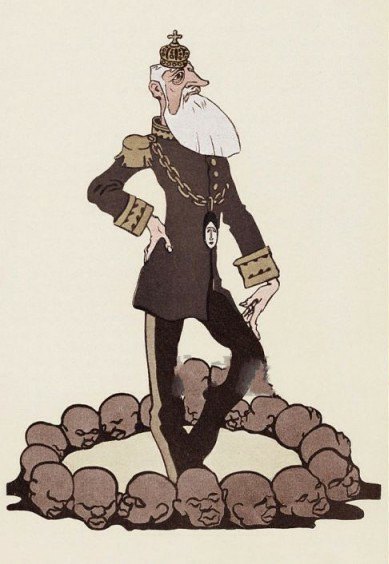

Leopold’s crocodile tears

Like Putin today, Leopold II publicly condemned enslavement while acting in direct contradiction to his words. The rhetoric of the Belgian monarch, however, was not anti-colonial but abolitionist, aimed at opposing the slave trade and slavery itself.

For most of the 20th century, liberation movements in the Global South focused primarily on colonialism; in the 19th century, the struggle centred on slavery. Initially, it was not slavery as such that was outlawed, but the slave trade. The first state to do so was the united Danish–Norwegian monarchy in 1803. In 1807, Great Britain followed suit. At that time, the British Navy — the largest in the world — began intercepting foreign ships transporting enslaved people. In 1833, the British Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which freed all enslaved people in British colonies.

Thus, the West moved from abolishing the slave trade to abolishing slavery itself. Soon, another major colonial power took the same step: France abolished slavery in its colonies in 1848. In the United States, the abolitionist North prevailed in the Civil War of 1861–1865, and slavery was prohibited by the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution. Even the Russian Empire abolished serfdom in 1861. Finally, in 1888, Brazil became the last country in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery. Against this backdrop, anti-slavery rhetoric gained great popularity in Brussels, and King Leopold II was quick to adopt it.

Leopold’s power in Belgium was limited. Like most European monarchies of the time, Belgium was constitutional. Leopold II possessed neither extensive political authority nor significant personal wealth. Nevertheless, power and money became his obsession, and he decided to pursue both in one place only — Africa. Observing how British and French monarchs profited from African resources, he sought the same. However, almost the entire African coastline — the most valuable colonial asset at the time — had already been claimed. In the 1870s, Scottish missionary David Livingstone and Welsh explorer Henry Morton Stanley charted the Congo River, which runs deep into the African continent. Leopold recognised this as his opportunity.

By that time, overt colonisation through conquest and enslavement had fallen out of favour. As a result, Leopold II could enter Africa only by presenting himself as an altruist, philanthropist, and opponent of the slave trade. In the eastern regions of the continent, however, the slave trade had not disappeared. Muslim traders had continued exporting enslaved Africans to the Arabian Peninsula since before the arrival of the Portuguese in the 15th century, and this practice persisted into the 19th century despite Western abolitionist efforts. Leopold II pledged to put an end to it — a promise that was welcomed in European capitals.

His primary objective, however, was to seize African land. Direct expropriation from local populations was no longer acceptable, so Leopold relied on treaties concluded by his emissaries with local chiefs. The chiefs often did not understand what they were signing, and the process itself was deeply manipulative. In contemporary terms, this would be described as corporate raiding. Through such methods, Leopold II acquired a territory 77 times larger than Belgium. Even the name of the new state — the Independent State of Congo — was misleading. Initially, its territories enjoyed a degree of self-government, but this quickly gave way to absolute rule by the king. Leopold also assured Europeans and Americans that the Congo would be a free-trade zone open to all, a notion that aligned well with the liberal ideas of the era. In practice, however, all profits from the export of rubber, ivory, and other resources flowed directly into the Belgian king’s personal accounts. To this day, no audit has been able to determine the full extent of the wealth he appropriated. Similarly, it is unlikely that the true scale of Russia’s wealth appropriated by Vladimir Putin will ever be known.

New Moscow

Vladimir Putin now claims that Russia has never been a coloniser. In reality, it was — particularly in Africa. Both Leopold II and the Russian Empire joined the division of the continent too late, and therefore resorted to indirect methods to secure a foothold among the established colonial powers. Leopold relied on liberal rhetoric, while the Russians invoked the language of traditional values. They established an African colony under the guise of a spiritual mission, bringing with them large numbers of clergy of various ranks, from priests to monks. People in cassocks accounted for roughly one third of the settlement, which they called New Moscow. This “Moscow” was located on the territory of present-day Djibouti. The Russians intended to use it as a springboard for the colonisation of the Horn of Africa. This approach closely resembles the way in which Russia today employs the Russian Orthodox Church as an instrument of its neo-colonial policy. At the time, however, the Russians were expelled from Africa by the French. Today, Russia is pushing the French out of Africa through proxy dictatorial regimes under its control.

The cruelty of the “liberators”

In particular, French forces were expelled from Mali under the pretext of fighting colonialism. In their place, Russian mercenaries from the African Corps — formed from the remnants of the Wagner Group — became infamous for their extreme brutality towards the local population. According to the head of one rural community, the Russians are implementing a “scorched earth policy… The soldiers don’t talk to anyone. They shoot at everyone they see — without questions or warnings. People don’t even know why they are being killed.” The Russians behead their victims and commit rape. Testimonies describing their crimes in the Malian town of Moura include the following:

“For several days at the end of March 2022, FAMA (the Malian Armed Forces) and Wagner participated in the siege of Moura. Malian and Russian forces looted, detained, and executed hundreds of people. At least 500 people were unlawfully executed, some without any interrogation. At least 58 women and girls were subjected to sexual violence. The mercenaries stole jewellery and confiscated mobile phones, most likely to prevent people from recording their atrocities.”

These events took place at the same time as similar crimes were being committed by Russian forces in Bucha and other Ukrainian cities. In Africa, such actions were — and continue to be — carried out under the guise of combating terrorism and colonialism.

Likewise, Leopold II, under the pretext of fighting slavery, brought to the Congo a level of cruelty that had largely disappeared from Africa by that period. Leopold’s administrators used terror to force the Congolese population to work beyond the limits of human endurance. Numerous testimonies of these atrocities have survived. Among them are the following:

“I knew Malu Malu (the African name of a lieutenant in Leopold II’s private army in the Congo). He was very cruel; he forced us to bring him rubber. One day, I saw with my own eyes how he killed a local man named Bongianga simply because, among the fifty baskets of rubber that had been delivered, he found one that was not full enough. Malu Malu ordered a soldier named Tshumpa to seize Bongianga and tie him to a palm tree. There were three sets of ropes: one at knee height, the second at stomach height, and the third binding his hands. Malu Malu had a cartridge belt around his waist. He took his rifle, fired from a distance of about 20 metres, and killed Bongianga with a single bullet.”

Another local witness, named Mputila, testified:

“As you can see, my right hand has been cut off… When I was very young, soldiers came to my village to fight over rubber. As I was running away, a bullet grazed my neck and left a wound, the scars of which you can still see. I fell down and pretended to be dead. A soldier cut off my right hand with a knife and took it away. I saw that he was carrying other hands as well. My father and mother were killed on the same day, and I know that their hands were also cut off.”

The cruelty of Leopold II’s soldiers is comparable to that of Putin’s forces in both Africa and Ukraine. There are numerous other parallels between the two regimes. For instance, a significant proportion of the soldiers serving under Leopold II and Vladimir Putin were janissaries — local children who had been abducted from their families or orphaned. Both systems established camps in which children were raised and trained to kill their own people. The following instructions were issued personally by Leopold II:

“We must create three children’s colonies. One in Upper Congo, near the equator, specifically military, with clergy for religious instruction and vocational education. One in Leopoldville under the leadership of the clergy, with a soldier for military training. One in Boma, as in Leo… The purpose of these colonies is, first and foremost, to provide us with soldiers.”

Leopold was assisted in the re-education of children by certain representatives of the Catholic clergy. Today, the Russian Orthodox Church is playing a similar role in support of Vladimir Putin. The following personal testimony, received privately from Russia and published here for the first time, illustrates this practice:

“There are camps in Russia that are directly subordinate to the state, and others that are run by various public organisations. If it is a state Temporary Accommodation Centre (TAC), it is most likely forbidden to speak Ukrainian there, while any yellow-and-blue symbols are prohibited. In general, children are subjected to considerable pressure. If they identify as Ukrainians, this works against them, and many simply say that they are Russians. There are also various Orthodox organisations and Kadyrov-affiliated organisations. In essence, they are cannibalistic structures, doing the same thing, but with even greater zeal.”

Corruption

Not all Christian missionaries concealed or participated in Leopold II’s crimes in Africa. Some, on the contrary, exposed them. In the West, this triggered serious political and media challenges for the Belgian monarch. He sought to resolve these problems using methods strikingly similar to those employed by Vladimir Putin: intimidation and bribery. Leopold paid off newspapers and politicians and created sham charitable organisations designed to launder his reputation.

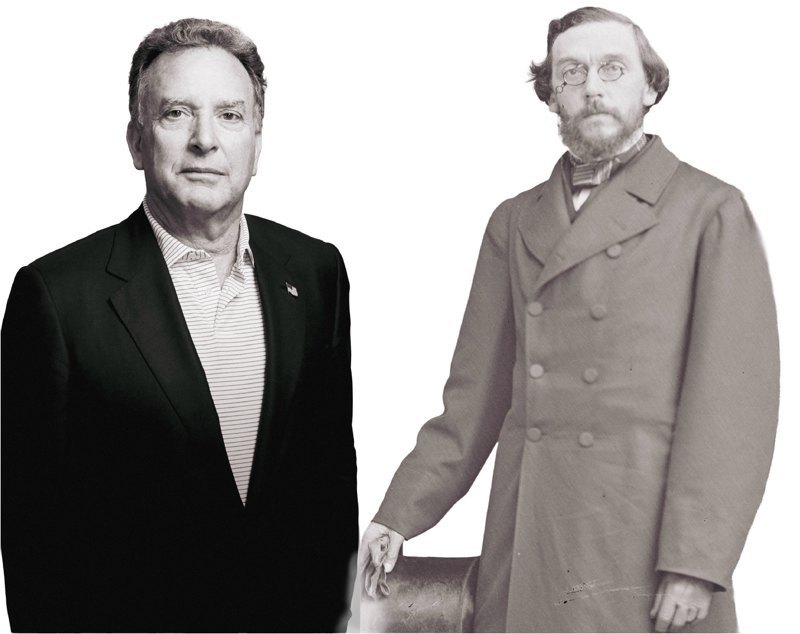

His greatest success came in the United States, where he hired lobbyist Henry Shelton Sanford. Although Sanford no longer held any official position, he was a personal friend of President Chester A. Arthur. In this respect, he closely resembled another presidential confidant, Witkoff. Sanford bypassed the US State Department, acting as an intermediary between the American president and the Belgian king. He also lobbied Leopold II’s interests in the Senate, which was responsible for recognising the king’s authority over the Congo. In particular, Sanford attracted the interest of John Tyler Morgan, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, by proposing the Congo as a destination for the resettlement of Black Americans. Through Sanford, Leopold also offered the United States zero tariffs on imports to the Congo and favourable conditions for investment.

These efforts produced the outcome Leopold II sought. In 1884, the United States became the first country in the world to recognise his rights over the Congo. Other Western powers strongly opposed this move, as they were already aware of the crimes against humanity being committed there. German Kaiser Wilhelm II is even reported to have described Leopold as “Satan and Mammon in one person”.

As with Ukraine today, it was Britain that led the campaign against Leopold II’s crimes in the Congo. Edmund Dene Morel was the most prominent exposer, supported by leading cultural figures such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Joseph Conrad, and influential church leaders. Under pressure from British public opinion and, in particular, the government, King Leopold II was eventually forced to relinquish control of the Congo. However, he did not do so without compensation; the territory was sold to the Belgian state.

Purgatory after hell

Although the Belgian government brought an end to the most brutal forms of exploitation in the Congo, the plundering of the country’s natural resources continued. Moreover, Leopold II’s practices were never formally condemned; instead, they were deliberately ignored. The king remained a national hero in Belgium and was even presented as a role model to children in Congolese schools. The Belgian state never fully assumed responsibility for the exploitation. For example, in 2001, Belgian Foreign Minister Louis Michel sent a confidential memorandum to diplomatic missions worldwide, instructing them on how to respond to uncomfortable questions about Belgium’s role in the exploitation of the Congo: “Steer the conversation towards Belgium’s activities for peace in Africa today.” As in the case of Ukraine today, financial interests once again outweighed the pursuit of justice.