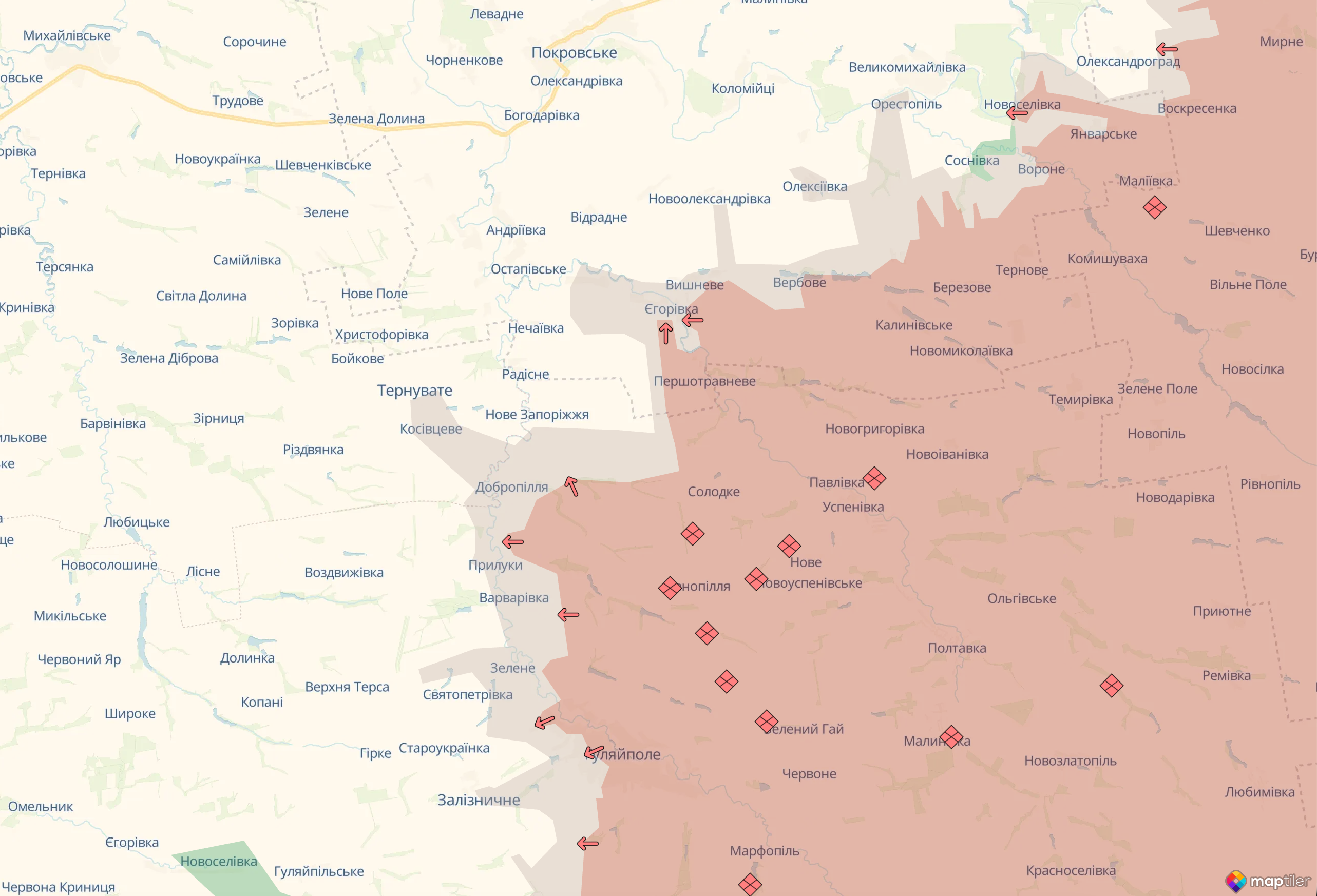

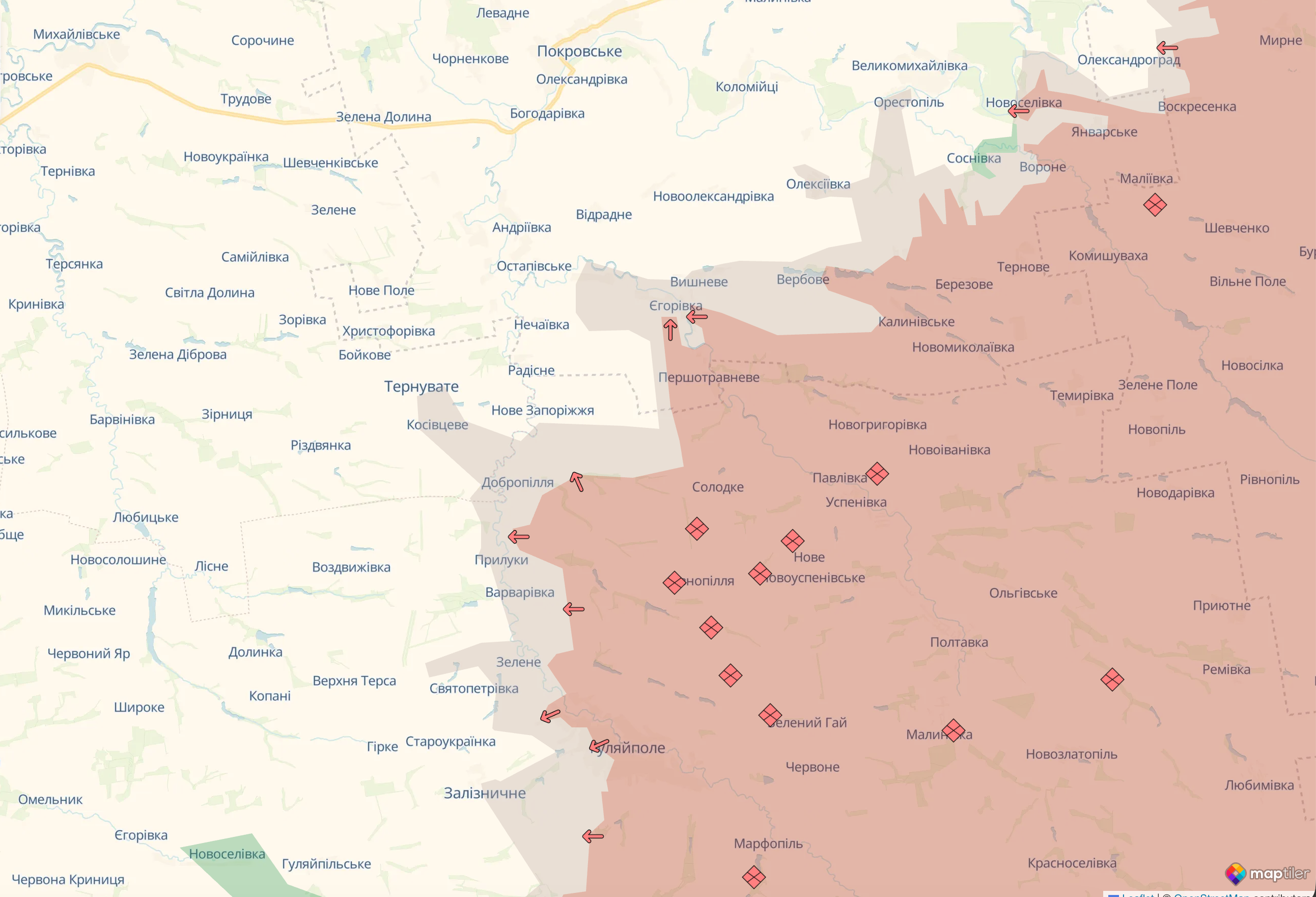

To understand the geography of the events: they are unfolding in the Oleksandrivske and Hulyaypole directions, most intensely at the junction of Donetsk, Zaporizhzhya and Dnipropetrovsk Regions. According to summaries from the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the increase in combat intensity began on 12 February and, by the morning of 16 February, had reached 37 combat engagements per day, compared to 13 on 11 February. Active operations likely began as early as 6 February.

On 12 February, heavy fighting took place along the line Tsvitkove – Staroukrainka – Zaliznychne in Zaporizhzhya Region. The Defence Forces halted the forward units of the russian’s 5th Army with several counterattacks. However, south of Zaliznychne, russian units advanced along the railway by up to one kilometre towards Dorozhnyanka – Zaliznychne, gained a foothold on the outskirts of the latter, and broke through to the eastern outskirts of Tsvitkove.

On the same day, Russia carried out 15 attacks in the Hulyaypole area, advancing toward Dobropillya, Zaliznychne and Rybne, and launched airstrikes on Kamyanka, Verkhna Tersa, Vozdvyzhivka, Barvinivka and Luhivske.

The Defence Forces conducted a series of counterattacks along the axes of advance of the Russia’s 5th and 36th Armies. This not only significantly slowed the Russia’s westward push but, in some sectors of the front, forced them to retreat. The occupiers were driven out of Oleksiyvka and Orestopol. Units of the Defence Forces reached the outskirts of Berezove and Ternove and began fighting to liberate them.

On the Danylivka–Pavlivka axis, Russian forces were pushed back from Danylivka; Vyshneve, Yehorivka, Pershotravneve, Zlahoda and Rybne were liberated, and the Defence Forces began fighting for Pryvilne.

On the Ternuvate–Dobropillya axis, the Defence Forces expelled Russian infantry from Ternuvate and Kosivtseve, crossed the Haychur River, and liberated Dobropillya.

On the Vozdvyzhivka–Varvarivka axis, Defence Forces units drove the russians out of Pryluky and Olenokostyantynivka, crossed the Haychur River, and began fighting for Varvarivka.

The following day, 13 February, a clearer operational picture began to emerge in the area where our troops, unexpectedly for Russia, appeared to have embraced the principle that defence must be active. Three main axes of action took shape:

• Sosnivka–Ternuvate, where the 2nd Battalion of the 425th “Skelia” Assault Regiment broke through the defensive line of the Russia’s 69th Cover Brigade of the 36th Army;

• Stepove–Berezove, where the 92nd Assault Brigade and the 67th Mechanised Brigade breached the positions of the Russia’s 186th Motorised Rifle Regiment (Territorial Troops);

• toward Novohryhorivka, where the 2nd Battalion of the 95th Air Assault Brigade and units of the 82nd Air Assault Brigade broke into the rear of the aggressor’s 36th Army, which is fighting further west in the Solodke–Zlahoda area.

At the same time, other assault units of the Defence Forces attacked from a bridgehead on the right bank of the Haychur River toward Zlahoda and Solodke. The defence of Russia’s 36th Army in the Danylivka–Yehorivka–Vyshneve area began to waver, and some Russian units started to withdraw.

Overall, by the evening of the 13th it was clear that the Defence Forces had achieved positive momentum in seven areas at once. These may have seemed like local actions, but the well-coordinated counterattacks within the operational zone of the Russia’s “Vostok” grouping over the course of two days led to the destabilisation of the Russian defence in its tactical zone along several axes simultaneously. Forcing the headquarters of the “Vostok” grouping to respond at the same time to sharp changes in the operational situation across multiple sectors of the front reduced command and control, further impaired coordination (which the enemy has notably lacked throughout the war), and exposed emerging gaps in Russian defences north of Hulyaypole.

When we speak about command and control and coordination, we must remember the material foundation of any such system — communications. And suddenly, to the world’s surprise, it emerges that the Russia’s tactical communications are built on the American Starlink system.

And it just so happened that the moment Musk switched off the “grey” terminals, our troops launched a “series of coordinated counterattacks”! Without Starlink, russian aggressor instantly lost operational control over small assault and infiltration groups, coordination of KAB air strikes and UAV attacks, as well as battery- and gun-level artillery fire. A communications system once touted as resistant to jamming simply stopped working.

Now the once-so-called second army in the world is hastily reverting to radios from the early days of the invasion, deploying field Wi-Fi and taking other urgent measures — many of them with a distinctly Chinese flavour.

Add to this the fact that the 82nd Brigade, along with the 2nd and 13th battalions of the 95th Air Assault Brigade, struck at the junction of Russia’s 29th and 36th Armies near Novohryhorivka, while the 24th and 475th assault regiments hit the seam between the 36th and 5th Armies, pushing towards Rivnopillya. In other words, coordination had already been shaky, communications patchy at best — and then Ukrainian assault units hit precisely where it hurt most.

By 15 February, it became clear that the Defence Forces were wiping out the gains made during the previous three months of Russia’s offensive. The most significant advance was along the Ternuvate–Uspenivka axis — moving west to east, pushing the line of contact farther from Zaporizhzhya, while simultaneously pressing Russia from north to south, from Pokrovsk to the same Uspenivka. This disrupts Russian battle formations, complicates manoeuvre and logistics, and turns any withdrawal into chaos.

It also buys time for engineering units to steadily reinforce defensive lines along the hypothetical route of any Russian advance towards Zaporizhzhya. Similar fortification works are under way around Pokrovsk, which cannot be bypassed on the road to Zaporizhzhya.

Speaking at the international Combat Engineer & Logistics 2026 conference in Krakow, Poland, Brigadier General Vasyl Syrotenko, Chief of the Engineer Troops of the Support Forces Command of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, noted that the role of military engineers is undergoing a strategic-level transformation. Engineering troops are becoming the “architects of the battlefield”, responsible for the entire territory of the state, the shaping of defence, manoeuvre, and the use of terrain in the interests of operational success. A fundamentally new task has also emerged: anti-drone protection of troop movement routes — in other words, creating protected movement corridors to preserve mobility and reduce personnel and logistics losses under conditions of constant Russian aerial surveillance. As we can see, there is no shortage of work.

Between 6 and 16 February, the Defence Forces effectively halted the advance of Russia’s “Vostok” force grouping and, through successful counterattacks, pushed Russian forward units back by 9–10 kilometres in certain sectors.

Is there cause for optimism? Not exactly.

This is not a counter-offensive, nor even a counterstroke. It is a series of carefully planned and prepared counterattacks on selected axes — stabilisation measures of a purely tactical level. For context, 10 kilometres corresponds roughly to the depth of a first-echelon regiment’s battle formation — no more. One should not expect sweeping envelopments, encirclements or cauldrons, although there are visible signs of an attempt to break into the rear of the occupiers’ 36th Army.

The Defence Forces exploited the exhaustion of forward elements of Russia’s 5th and 36th Armies after two months of offensive operations, the sudden deterioration in command and control within the “Vostok” grouping, and coordination problems — all of which undoubtedly reflect positively on Ukrainian commanders at every level, from the Commander-in-Chief down to the brigades and battalions mentioned above.

The Defence Forces have gained an operational-tactical opportunity to build on their success. However, Russia still holds several trump cards. It retains sufficient operational reserves on the Oleksandrivske and Hulyaypole axes — by even the most conservative estimate, no fewer than two brigades.

Russia is also capable of swiftly redeploying the 41st Army of the “Centre” force grouping or its 90th Tank Division from the Pokrovsk axis (which is relatively straightforward), or the 18th Army of the “Dnepr” grouping from the Prydniprovske axis (somewhat more complicated, simply because of the longer distance).

The Defence Forces do not enjoy air superiority. They have parity with Russia in UAVs and, unfortunately, lack sufficient combat-ready reserves — which dampens hopes of transforming tactical gains into operational success.

What can be stated with absolute clarity is that through their active operations over the past ten days, the Defence Forces have completely disrupted Russia’s timetable for preparing the “Vostok” and “Dnepr” groupings for the Orikhiv–Zaporizhzhya offensive operation planned for this summer.

What is happening now? Fierce fighting continues near Dobropillya. Defence Forces units are consolidating positions in Pryluki and Tsvitkove, which they have cleared. Brutal close-quarters combat is under way in Varvarivka and Olenokostyantynivka. Russian forces are being squeezed out of key defensive hubs, with the disruption of logistics across the entire tactical depth among the primary objectives. Assault brigades and regiments are pressing along the Verbove–Vyshneve–Stepove–Ternove line. Russian forces are becoming exhausted, although they are attempting active infiltration towards the area east of Havrylivka.