Who was Halyna Kuzmenko?

The exact number of Nestor Makhno’s official wives is unknown. Not every episode of his personal life can be fully fact-checked. For instance, it is said that his mother almost forcibly married him off when he was very young — if this marriage actually happened, it was short-lived. Later, the anarchist married Anastasiya Vasetska, a fellow villager, which is a confirmed fact. Vasetska gave birth to Makhno’s son, who died almost immediately.

After that, a Jewish woman named Sonia appears in Makhno’s marital record — she may have existed, but there’s no solid evidence. Then there was a telephonist named Tina (surname unknown) from the village of Velyka Mykhaylivka; their marriage lasted about a year. At the same time, Makhno had a relationship with the famous Marusya Nikiforova, leader of anarchists in southeastern Ukraine. This continued until 1919, when Nestor married Halyna Kuzmenko.

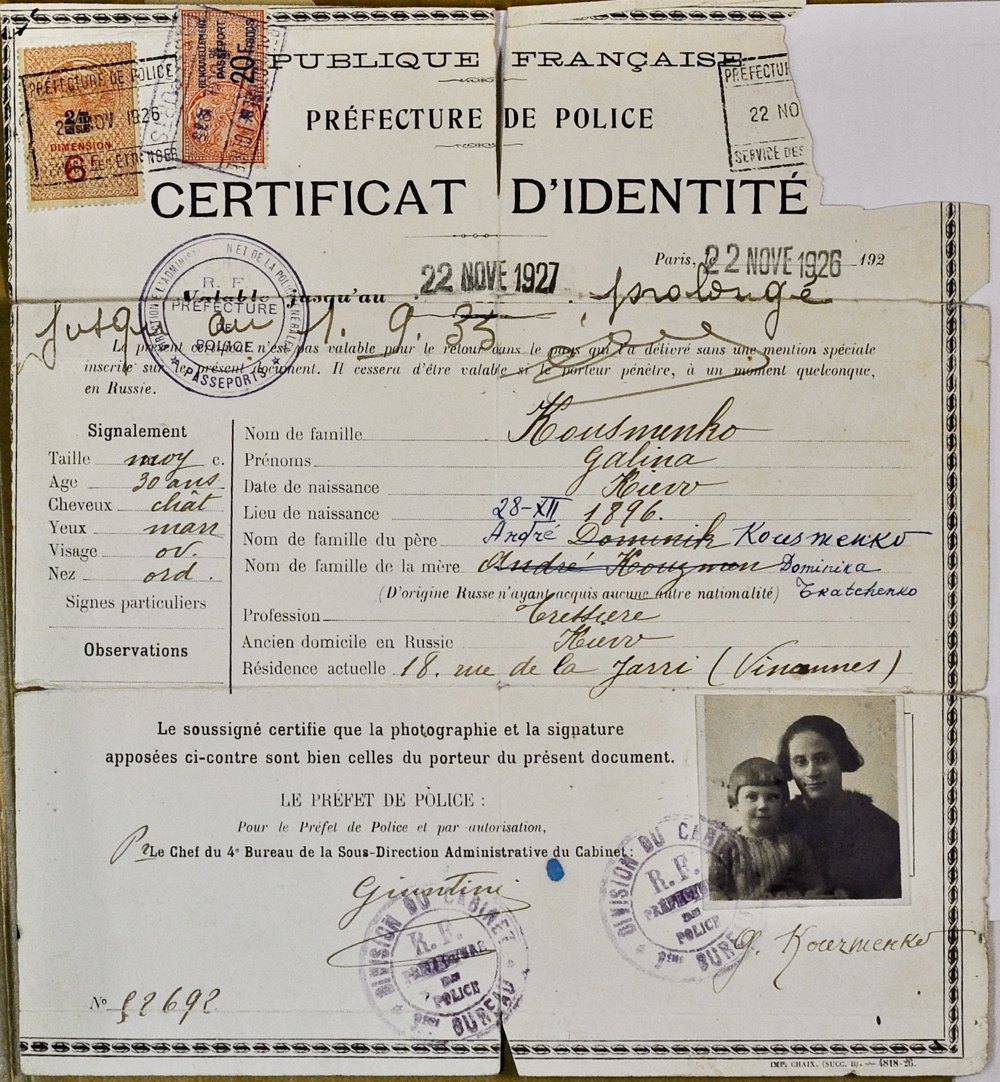

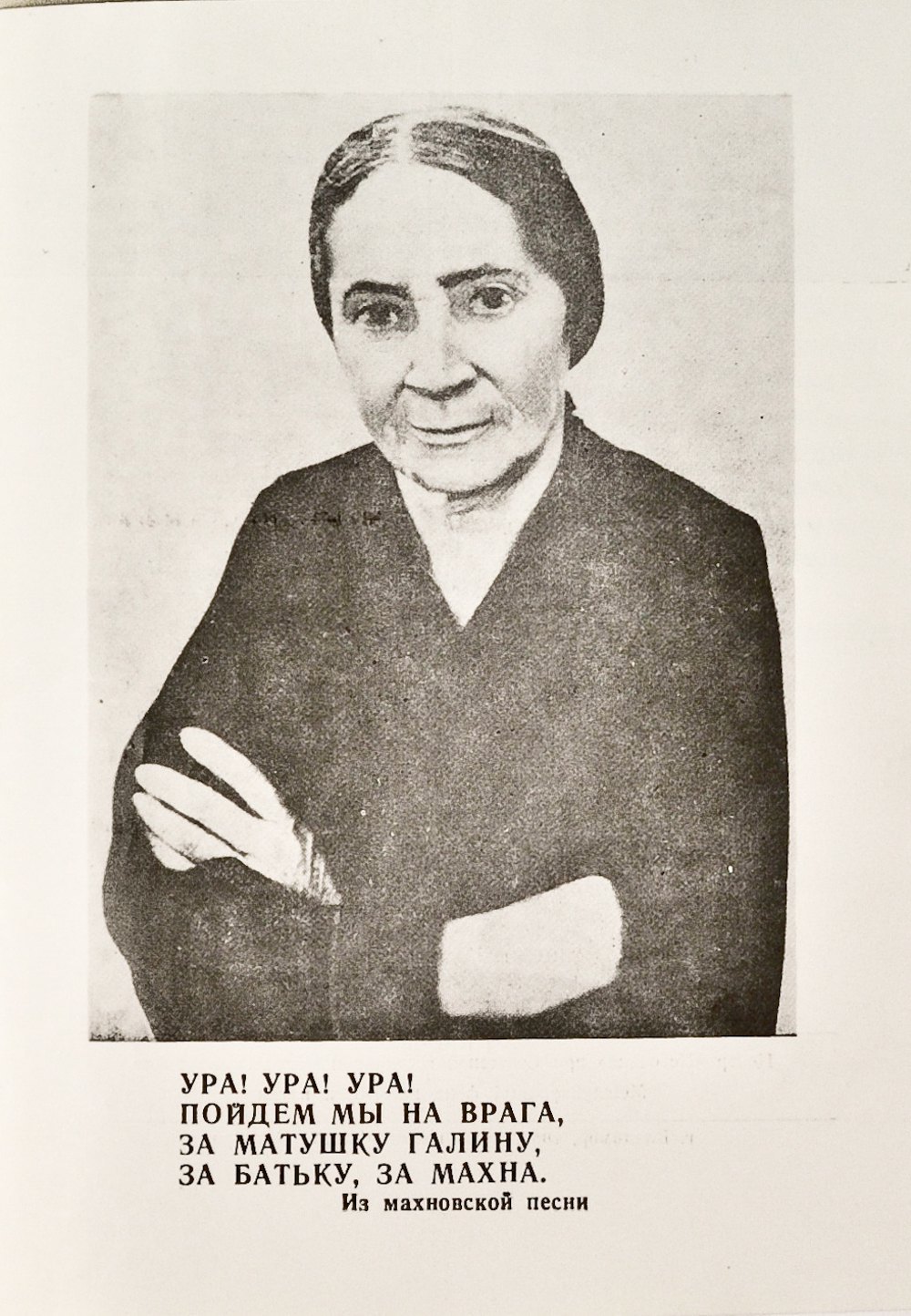

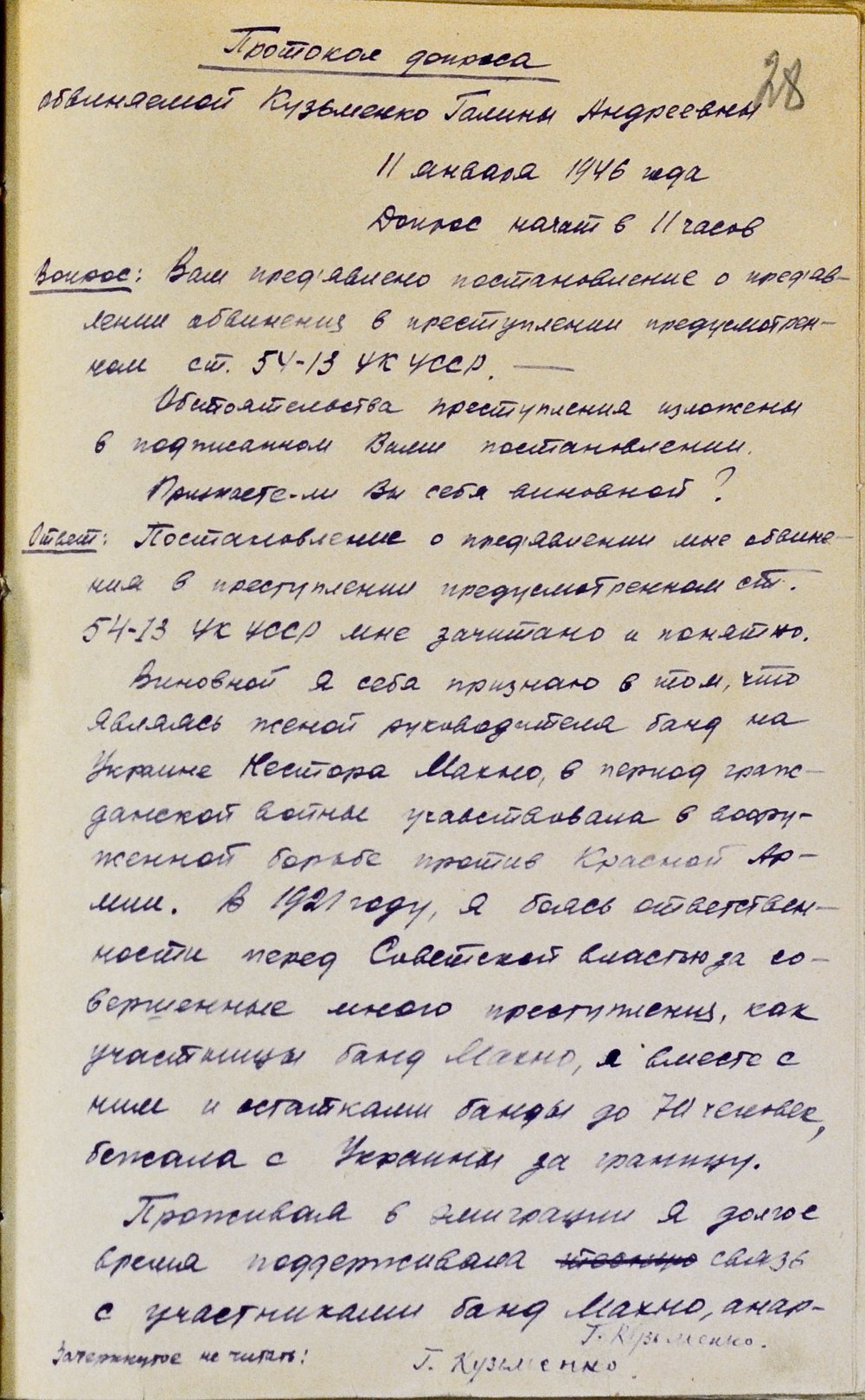

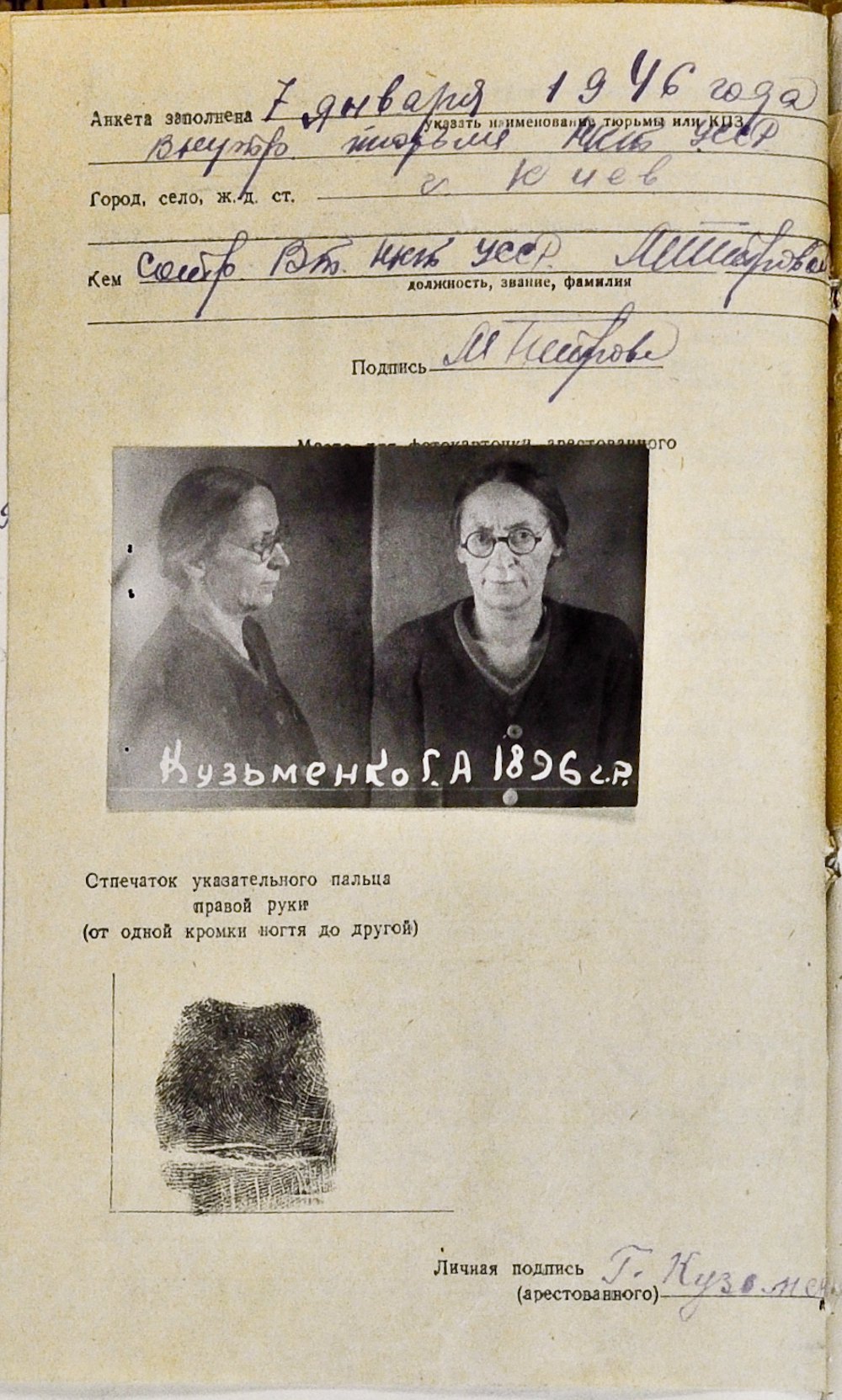

“Halyna Kuzmenko in 1921 fled the Soviet Union with Makhno’s detachment. She was Makhno’s wife. From 1921 to 1945 she lived abroad. She was a member of the Union of Ukrainian Citizens in France,” — so begins Halyna Kuzmenko’s criminal case. It goes on to describe her active participation in the fight against the Red Army, and her equally active anti-Soviet work abroad.

So what really happened?

In reality, the accused denied all the charges. Halyna was only 23 when she married Nestor Makhno. A young teacher — fun fact! — she had graduated from a women’s seminary and went on to teach children Ukrainian. She taught her subject at a two-class school in Hulyaypole. It was there that the paths of Halyna, the Kyiv-born teacher, and Nestor, a local, first crossed.

In 1919, Makhno’s detachments were smashing Denikin’s army, halting its advance toward Moscow. This impressed the Bolsheviks, who proposed a tactical alliance with the batko.

Without Makhno’s help, it would have been hard for them to stop the advance of the White Army, particularly Wrangel’s forces. But as soon as Wrangel was defeated, the Reds turned their bayonets on Makhno’s units, whom they had considered enemies from the start. The Bolsheviks broke their agreements and began destroying Makhno’s followers, while the batko himself — seriously wounded — was forced to flee abroad. Halyna went into exile with Nestor. She outlived her husband (Makhno died in 1934) and it was there that she was later detained by NKVD agents.

Thus began her path back to her homeland. Halyna was brought to Ukraine, where she was tried and sentenced to eight years in prison. She was released in 1954. From that point until her death in 1978, another chapter of Makhno’s wife unfolded — one beyond the case preserved in the SBU archives.

Lenienstrasse 58, or transfer Berlin — Kyiv

Halyna and Makhno crossed the border and ended up in Romania. They stayed there for six months before heading to Poland, and from Poland — to Paris. Makhno would remain in Paris until his death in 1934. Halyna also lived there, but separately from her husband. Their marriage — she told the investigator during interrogation — fell apart in 1927 due to her work with the Union of Ukrainian Citizens in France.

“And what kind of Union is that?” asked the investigator, Senior Lieutenant Zhdanov.

“It’s a completely legal organization,” Halyna explained, “financed by the Soviet Union, but unofficially. Its purpose — literally — is ‘propagating the political ideas of the Soviet Union among Ukrainians and Galicians.’” Let’s note this moment: until now, no researcher of Makhno’s life had mentioned that the reason for the couple’s divorce was Halyna’s turn toward the “political ideas of the USSR.”

Presumably, Nestor saw this as a double betrayal — both ideological and personal. One might wonder how Makhno felt about Halyna’s work with the Union of Ukrainian Citizens. What did he think about his wife working for the “enemies” — those who fought against him and ultimately drove him from his homeland?

But the investigator doesn’t care about that. He asks about something else — the reasons for Halyna’s move to Berlin. “Unemployment,” she explains. First, Halyna’s daughter Olena moved to Berlin (in 1941), and then in 1942 Halyna joined her. So, when World War II was in full swing and the Germans were advancing successfully into the USSR, Halyna Makhno was working as a laborer in a German factory.

One might also logically wonder: what were Halyna Makhno’s political sympathies? Did she support the USSR? Did she maintain contacts with Soviet handlers? But the investigator doesn’t ask this, probably for his own reasons. Instead, he monotonously repeats the same questions: was Halyna part of the Ukrainian nationalist underground? Did she carry out anti-Soviet agitation? No, no, and again no, Halyna Makhno replies.

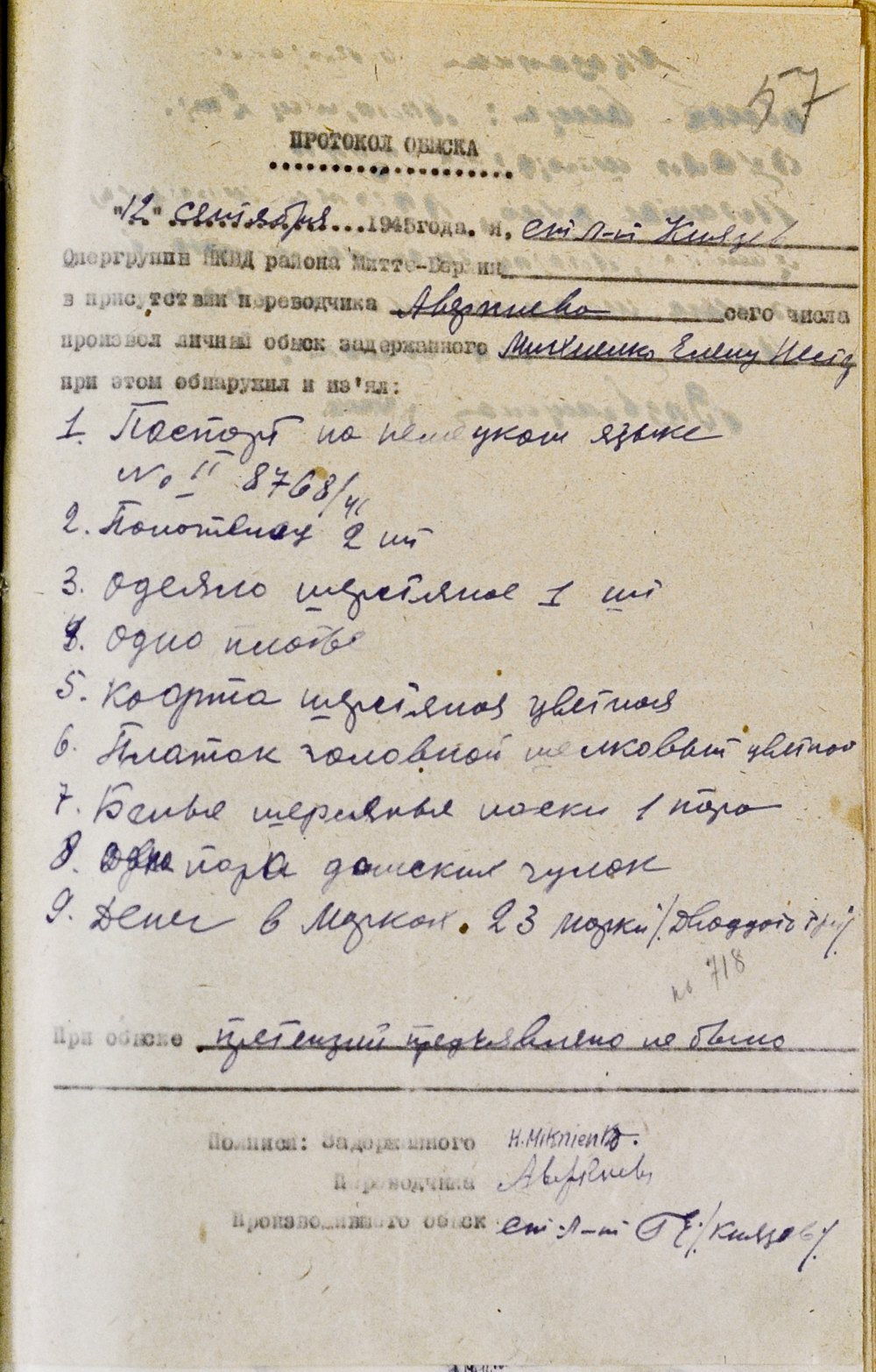

Halyna remained in Berlin until 1945, when the city was captured by Soviet forces. On 15 August that year, NKVD officers came to her home at Lenienstrasse 58. They seized German marks, her membership card for the Union of Ukrainian Citizens, German and French passports, and a Nansen certificate — what at the time served as an identity document issued by the League of Nations to refugees.

For her work for the USSR, the Soviet secret service “rewarded” Halyna with imprisonment and a criminal case. It was 1946. The 50-year-old wife of Makhno was repeatedly dragged in for interrogations.

Marital disputes over Makhno’s “atrocities” and gold

Investigator Zhdanov disregards any chronology. Again, he questions Halyna about her youth. She recounts certain biographical facts: her father, she says, was executed in 1919 “for ties to the Makhno forces.” At that time, her family lived in the village of Pishchanyy Brid, in what is now Kirovohrad Region. Her mother was also supposed to be executed, Halyna says, but she managed to escape. For a while, she and Halyna’s brother Stepan were hiding with Makhno’s detachment. The mother died in 1933 — it’s not hard to guess why, though Halyna doesn’t say.

Halyna, however, emphasizes that she herself never took part in any of

Was Halyna tortured into changing her testimony? Or perhaps blackmailed through her daughter? We will never know for certain — but the possibility exists, and it is a strong one. In any case, after a certain turning point, Halyna begins giving extensive statements: about an anti-Soviet SR organisation in Berlin, about her husband publishing the anarchist journal Delo Truda in Paris, about his contacts with European and American anarchists.

In conversation with the investigator, she increasingly uses the terms “Makhnovshchyna” and “Makhno’s bands.” The investigator, pointedly polite, addresses her formally. He asks where the valuables allegedly stolen by Makhno might be. Halyna confirms that back in 1919 “Makhno’s bands” had looted banks and pawnshops in Katerynoslav (now Dnipro). The haul was substantial — gold and cash. But where it all went, she says she does not know. “And your husband never told you?” the investigator asks. Halyna answers no.

She is sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment. Of all the charges, only two appear in the verdict: fighting against Soviet power during the civil war and anti-Soviet activity after leaving the country. Neither charge is supported by any real evidence, yet this seems to satisfy the prosecution. The Union of Ukrainian Citizens in France is not mentioned again in the case.

“My father is a bandit, I bear the surname Mikhnenko”

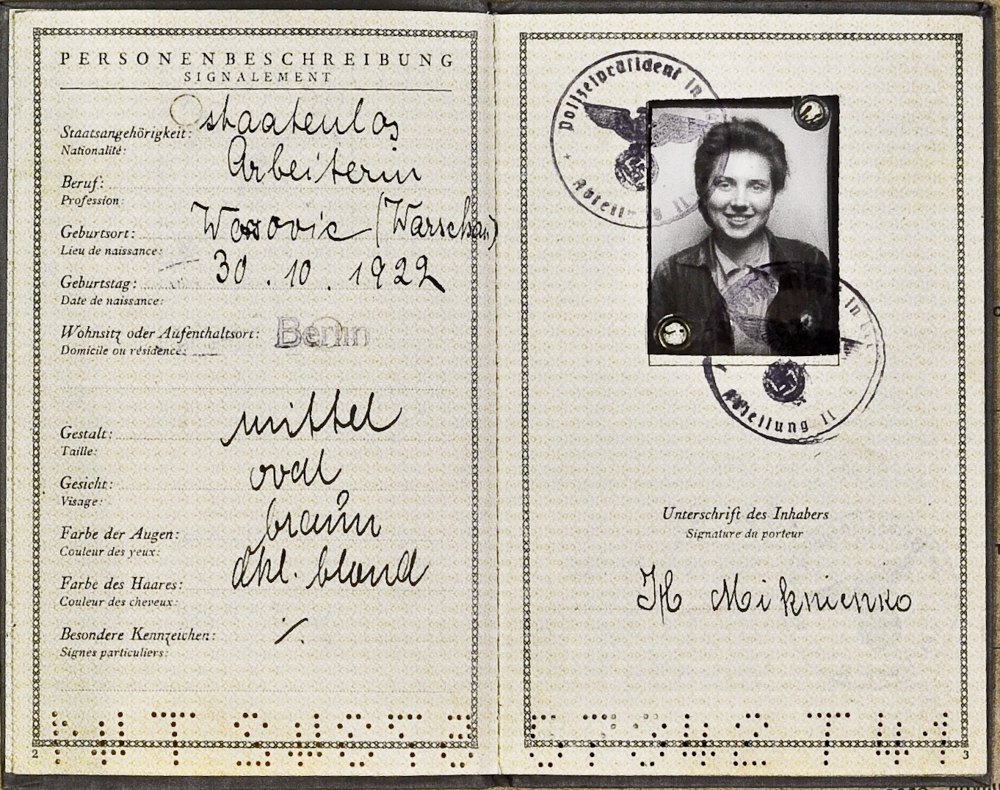

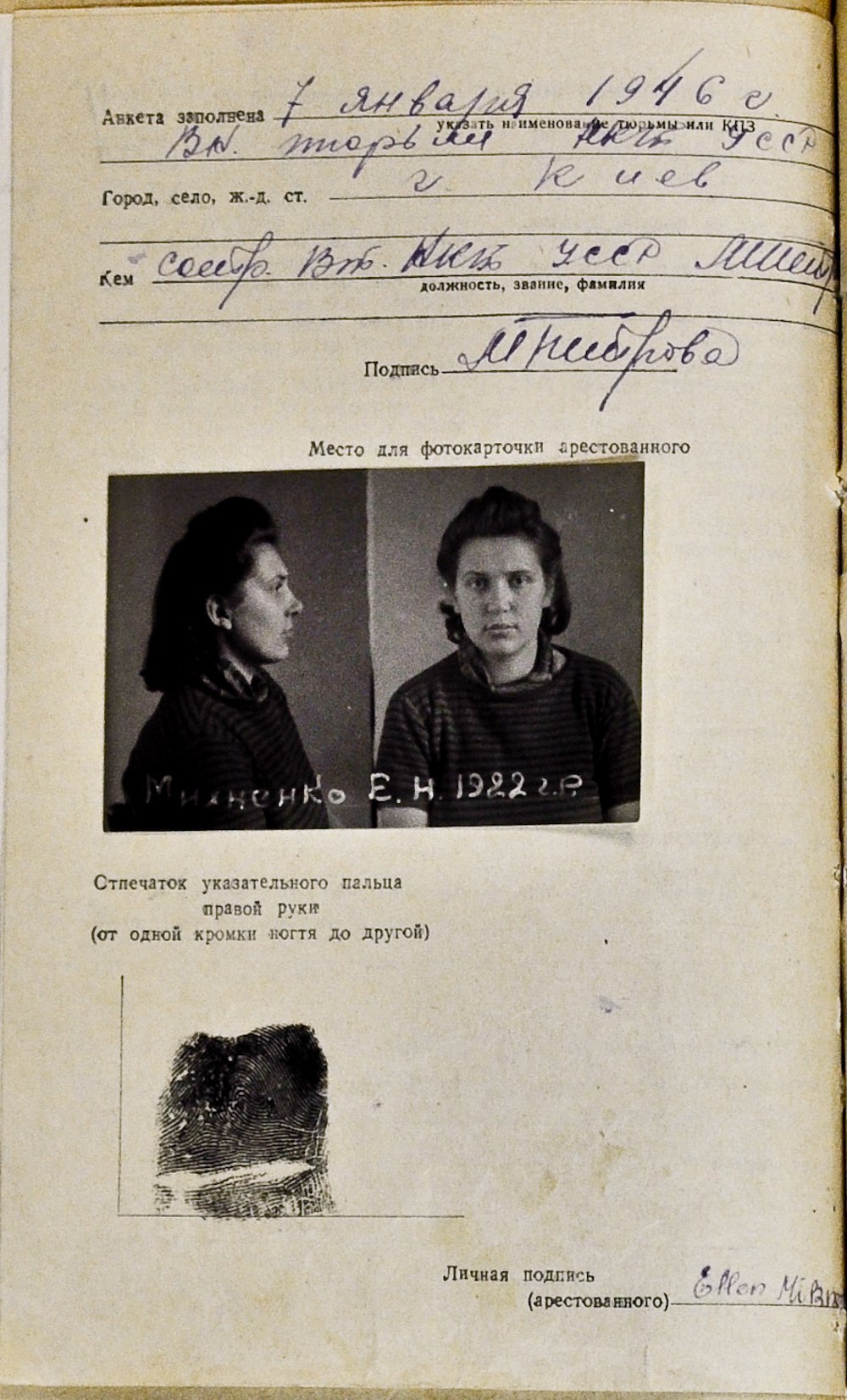

Senior Lieutenant Zhdanov then turns to Olena Mikhnenko. She was arrested in Berlin on 12 September 1945 and also transferred to Kyiv — to Prison No. 1 of the NKVD of the Ukrainian SSR.

Ukrainian Wikipedia carries an entry titled “Olena Nestorivna Makhno.” In reality, however, Olena bore a different surname — the original family name on her father’s side: Mikhnenko. That was the surname of her great-grandfather, although her grandfather Ivan had already “lost” part of it and become “Mikhno.” As the young woman explains to the investigator, in Paris her father resumed using the surname (spelled in the file as “familiye”) Mikhnenko — and she herself adopted it as well.

Her father’s legacy rolled over her fate like a steamroller. In reality, Olena had very little contact with Makhno during his lifetime. Let’s not forget — she was only five when Halyna Kuzmenko divorced Nestor. Olena’s childhood passed in Paris. She mastered French, spoke Russian poorly, and did not know Ukrainian at all. She signed her interrogation records in Latin script: Ellen Mihnenko.

Her “employment record” reads like a patchwork quilt. According to the case files, at sixteen — in 1938 — she had already learned shorthand, typing and clerical work. In 1939, she began studying textile pattern design and machine embroidery. In 1941, through a German labour exchange, she left for Berlin, where she found work at the Siemens factory.

At first, she worked in the inspection department, checking the quality of electrical goods. Later, after learning German, she became a translator at the same plant. Then another profession appears unexpectedly — until 1944, Olena Mikhnenko worked as a draughtswoman, and in 1944 she began training with a private dental technician. “With the capture of Berlin, she worked as a translator in the economic department attached to the main command of the Soviet occupation forces — until the moment of her arrest,” her case file states.

Olena was charged under the same article of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR as her mother — Article 54. In general, Article 54 covered “treason against the Motherland,” broken down into sub-paragraphs. In Halyna Kuzmenko’s case, it was 54.6 — “espionage.” For Olena Mikhnienko, it was 54.3 — “contacts with a foreign state.” The punishment for both “crimes” was the same — execution. Yet somehow, incredibly, both Makhno’s wife and daughter escaped the death sentence.

During interrogation, Olena agreed that her father was a “bandit,” but refused to plead guilty herself. Guilty of what, exactly? Quite reasonably, Mikhnenko pointed out that she knew about her father only from other people’s accounts — just as she knew about the civil war, which had ended before she was even born. Moreover, “my father did not raise me,” the young woman said.

“Raised in boarding schools in an anti-Soviet spirit”

The interrogations continued, now focusing on Olena’s adult life. “I do not admit that I was a German accomplice,” she stated. She added that she had been forced to go to Germany because in France, as a foreigner, she did not even receive unemployment benefits.

The investigator jumps abruptly from the 1940s back to the 1920s and again asks whom she knows among the “members of Makhhnovite bands.” “I don’t know anyone,” she replies.

And then — astonishingly — Mikhnenko is left alone. Mr Zhdanov even politely notes in his report that the suspicion brought against the detainee has not been substantiated. It would seem that her innocence has been established and she can go home. But no. The defendant is deemed “socially dangerous,” the investigator concludes, and must therefore be held accountable under Article 33 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR. This article did not refer to any specific crime; it concerned a vague “combination of offences.”

But what combination, exactly? The case file spells it out — a striking monument to its time. First, Olena travelled to Germany. Second, she worked there at a military factory. That alone made her an enemy of the USSR. Third, she had lived abroad. And fourth — she had been “raised there in boarding schools in an anti-Soviet spirit.”

What a revealing touch of proletarian resentment toward those “foreign boarding schools” in that wording. For Olena, however, there was nothing amusing about it. Her sentence was lighter than her mother’s, yet still severe: five years of exile. She served it in Dzhambul (Kazakhstan), where after her release from prison Halyna Kuzmenko joined her.

Both women remained there for the rest of their lives. According to accounts, Halyna longed to return to Ukraine, but relatives turned away from her, and she realised no one was waiting for her in her homeland. As for Mikhnienko, Ukraine meant little: she died in 1993 and could have visited Kyiv or Hulyaypole, but apparently felt no need to do so.

“She was sentenced correctly”

In 1960, Halyna Kuzmenko petitioned the Prosecutor’s Office of the Ukrainian SSR for rehabilitation. Without it, she explained, she could not receive a pension. “She was sentenced correctly,” the reply stated — therefore, no rehabilitation would be granted. The same applied to Olena Mikhnenko.

Both were rehabilitated only in 1989.

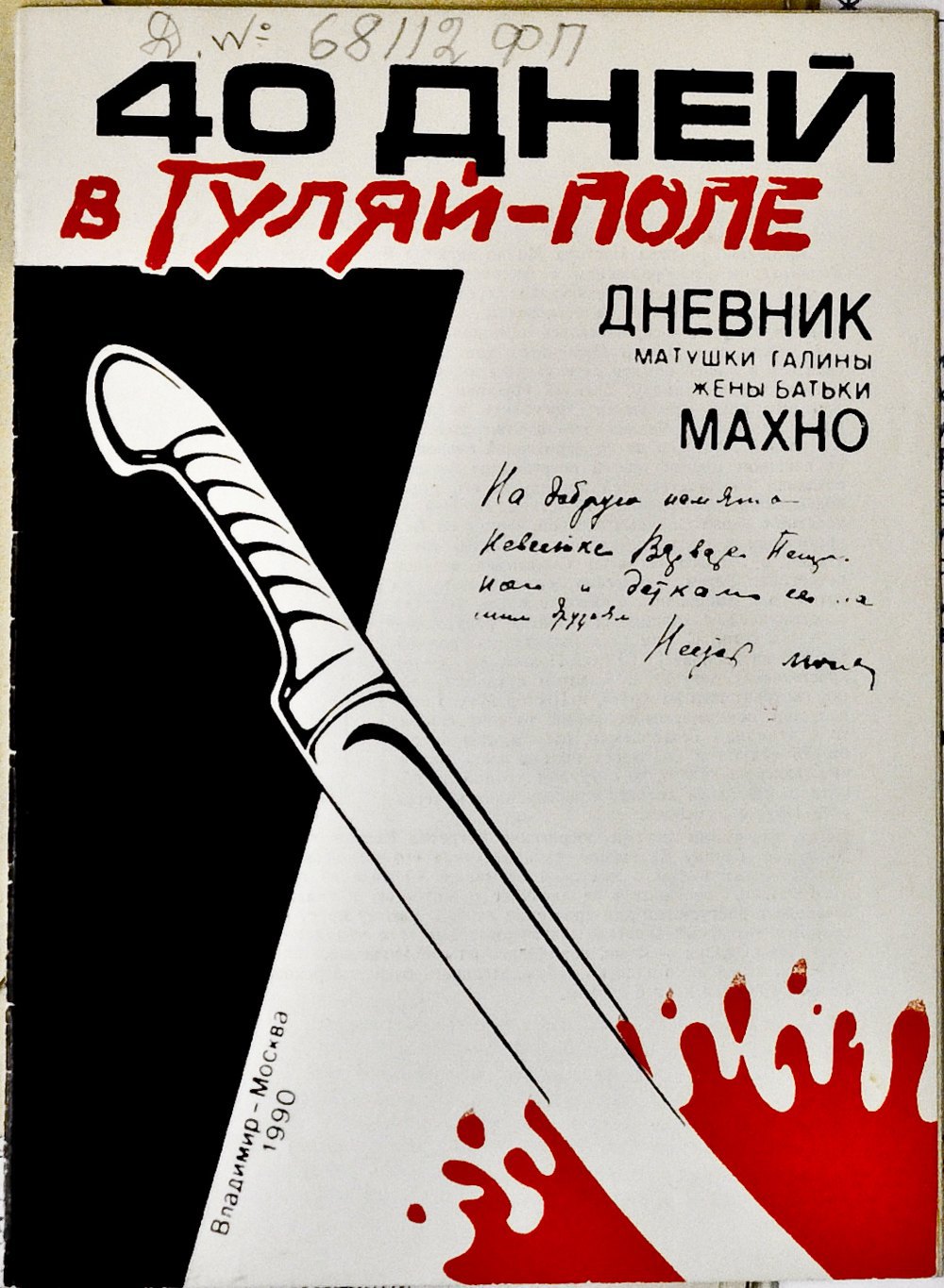

…Do they evoke empathy in a reader studying their case? With Halyna Kuzmenko, the answer is less straightforward. Though she told the investigator she condemned her husband’s cruelty, her diary frequently records entries such as “today such-and-such were shot.” The tone is disarmingly ordinary — like noting “we were brought fresh bagels,” a line that appears just below reports of executions.

Olena Mikhnenko, however, seems guilty of only one thing: being her father’s daughter. A father who, dying of tuberculosis, addressed her with his final words: “Be healthy and happy.” Happiness, however, did not follow. What followed was a path marked by pain and hardship. And that is no mere figure of speech: it is known that Mikhnienko vowed never to marry or have children. Branded the child of an enemy of the people, she did not wish such a fate upon her own descendants.