Partisans were that active only in Lithuania and Ukraine

Mr Saudargas, you are a physicist by education, not a historian. Why did you take on such a complex research topic as Stalin’s camps?

Because historical memory is crucial — for every state and every nation. Once, Professor John Hall from California [a professor of law at Fowler Law School] visited Lithuania and said: if a nation does not tell its own story, others will do it for them. And we know who those others are. The Russians constantly distort our history; their propaganda has been operating for decades. We must defend our past, write it ourselves and pass on this memory to future generations.

One Lithuanian partisan wrote in his memoirs (later found in the KGB archives): we — the partisans, rebels against the Soviet regime — are strong not only through our weapons but also through our spirit and heart. I believe we must build the patriotism of new generations upon the foundation of heroic narratives. Young people must know who our heroes are, how they built the state, and how they fought and died for it.

That is why I joined the historical memory expedition in 2012, visiting Krasnoyarsk and Irkutsk. We followed in the footsteps of Aleksandras Stulginskis (President of the Republic of Lithuania in 1920–1926 – Ed.) — the only president in the world who endured the Gulag (he was arrested in 1941 and exiled to Siberia; in 1952 he was sentenced to 25 years in prison – Ed.).

A year later, I organised an expedition to Vorkuta, and in 2015 I travelled to Kazakhstan to see the camps and places of exile. Later, we spoke about these experiences in schools and realised that almost no one knew about the large uprisings in the camps in 1953–1954 — in Norilsk, Vorkuta and Kengir — where thousands of prisoners essentially staged a revolution. Awareness of this in society was practically non-existent.

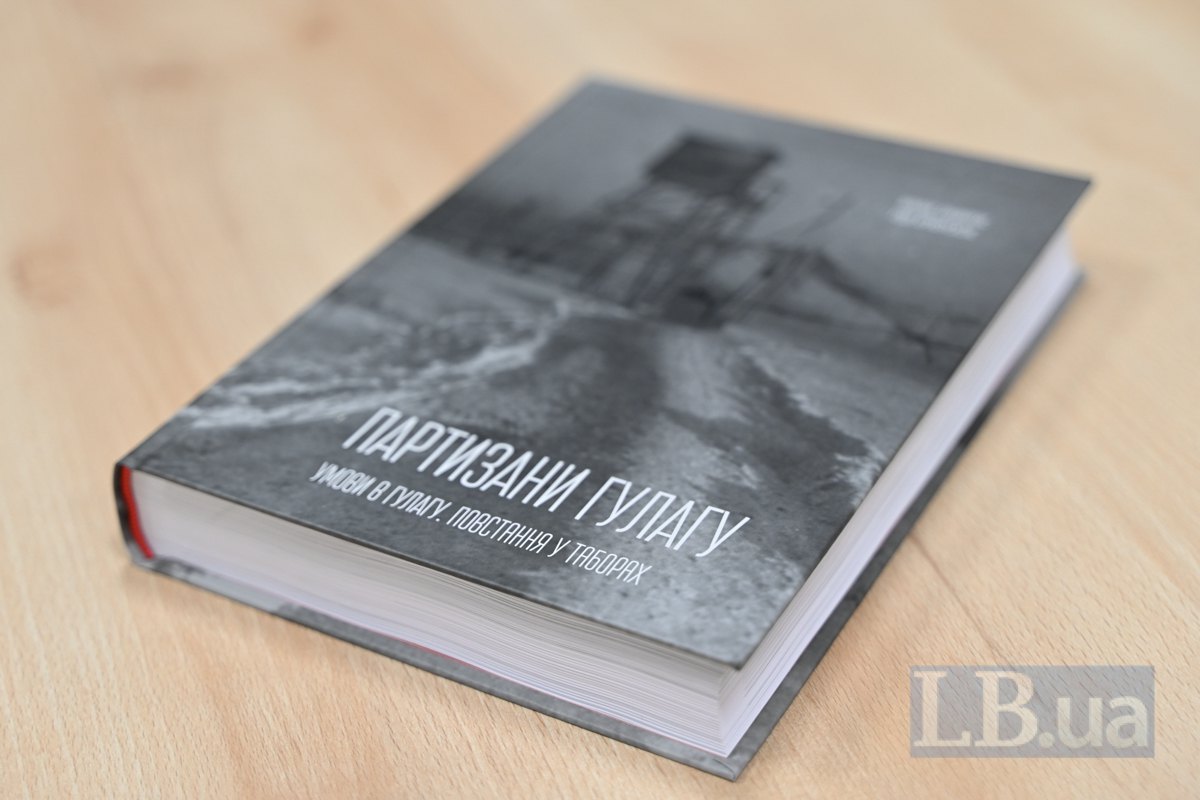

Together with my co-author, Goda Krukauskene, we wrote our first book, Partisans of the Gulag, in Lithuanian to tell the story that Ukrainians and Lithuanians fought the communist regime not only in forest hideouts but also in high-security camps. We then published a second book, Prisoner’s Limit, about the brutal conditions of detention and forced labour in the camps — how prisoners were fed, why their health deteriorated, what methods of torture were used, and how relations developed between criminal and political inmates. We discovered that young people had no understanding of what the Gulag was, where Siberia was, or who Stalin was.

Later, we went to open the Honorary Consulate of Lithuania in Lutsk together with Verkhovna Rada Deputy Ihor Guz and Lithuanian Ambassador to Ukraine Valdemaras Sarapinas. They encouraged me to translate the books into Ukrainian. I merged both works into a single volume, which I am now presenting as a special edition.

I thought that perhaps there was some personal history behind my interest in the subject.

The book contains the memoirs of my godfather, who spent a year in a KGB prison in Vilnius. He was one of the last political prisoners in Lithuania. Together with my father, they secretly printed and distributed newspapers and literature that were illegal during the Soviet era. The KGB tracked down my godfather, but he did not betray my father. My father’s uncle was sent to the camps and worked in a coal mine in Vorkuta.

Why is it important for Ukrainians to read about that long-ago struggle now, when we are already at war with Russia?

Because Putin is the reincarnation of Stalin, and Putin’s Russia is the reincarnation of the USSR. Russia has not known democracy since tsarist times; it is an autocracy, a dictatorship, an imperialist state that constantly poses a threat to its neighbours. Both Ukrainians and Lithuanians have long fought side by side against this red plague — this enemy. You had the UPA, and we had the ‘forest brothers’ (a resistance movement against Soviet occupation in the Baltic states – Ed.). Only in Ukraine and Lithuania did armed resistance continue for ten years after the war; nowhere else among the republics did this happen. And now you are continuing this struggle, fighting the same enemy across centuries. We must help you in every way we can, because we must put an end to imperialist Russia once and for all.

Russians are stirring up the situation with drones and propaganda

Let me ask you about the current struggle — what is the situation in Lithuania? It is no longer very calm: the airspace has been repeatedly violated by drones, balloons and even fighter jets. How is this viewed in Lithuania — as provocations or accidents?

It’s very simple — this is a hybrid war. It is not yet an open conventional war, but it is already underway. It starts with propaganda, which is being spread constantly. Society’s firm position on educating young people through historical memory is an antidote to that propaganda.

The problems began with the migrant crisis that Alyaksandr Lukashenka created for Poland, Lithuania and Latvia (the transfer of migrants to the EU borders organised by the Belarusian regime in 2021 – Ed.). I myself took part in the events as a member of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union and saw with my own eyes that people from Iraq, Syria and Africa somehow ended up in Minsk and then crossed the forest into Lithuania. It was a real attack, because our country is too small to accept thousands of migrants at once. We built a fence, but now the smugglers have obviously started using other means, in particular helium balloons, which float into our territory. This is a very big problem. I was surprised that I was able to fly to Warsaw, because Vilnius airport was closed from the evening before and the following day. I do not know how I will fly back, because there is a daily threat of the airport closing. This is a huge loss — in one evening 6,000 passengers were affected. It is a great blow to the economy and the country’s image, as well as to tourism. A couple of balloons were launched, and flights were paralysed. It is impossible to continue living like this.

That is why we are now taking measures and looking for ways to combat this new phenomenon. On top of that, there are drones. Only a few drones have fallen in Lithuania (while there was a massive attack in Poland). But we still lack the means to combat them; we are aware of this. We are attempting to form a ‘drone wall’, but we will not be able to intercept hundreds of drones if they fly en masse. We are therefore feeling the impact of these hybrid attacks acutely.

To counter them, we have increased the defence budget from 2% to 5.3% of GDP. That is significant.

The Prime Minister of Lithuania recently stated that, in extreme cases, they are even prepared to shoot down such flying objects. In your opinion, what could these extreme cases be — fighter jets with KABs on board?

It is difficult for me to comment on the Prime Minister’s words because she is new to government and I hope she is working to resolve the problem. Everything that flies in our sky must be shot down, no matter what, but we lack experience. Our party (Fatherland Union — Lithuanian Christian Democrats – Ed.) has brought in military experts who served in Ukraine for two to three years and have now returned. They are UAV operators and understand the issue well. They have developed and presented a concept and a programme for what the line of defence on the border should look like — fortifications, minefields, etc.; what the ‘drone wall’ should be like; what sensors should be installed. They even persuaded (I think, aided by our party) the first European Commissioner for Defence and Space, Andrius Kubilius, and Ursula von der Leyen. About a month ago, she said in her speech: “We must listen to our Baltic friends and build a ‘drone wall’ there.” She promised to build it.

‘Dragon’s teeth’ have already been laid along the border with Russia. How else are you fortifying your defences?

Yes, but that is not enough. We have entire warehouses in some places near the border, and we can lay out more if necessary. We have already withdrawn from the Ottawa Convention (which prohibits the use, stockpiling, production and transfer of anti-personnel mines). Steps are being taken, but they are insufficient. We need to start digging ditches, trenches and building bunkers today. We should not wait for a special signal, but strengthen the border. It does not cost much and can be done gradually.

The ‘drone wall’ is more complicated. Everything is changing rapidly in this area — we may purchase thousands of drones and store them in a warehouse, but in a year they will already be obsolete. This means that we need to invest in the military industry — in a kind of ecosystem that will be ready to deliver products that are relevant in the future. In the meantime, it can manufacture equipment for Ukraine. You will use it today, and we will build up the capabilities of our defence industry and develop this ecosystem.

Has the Border Guard Service noticed any suspicious activity along the Russian and Belarusian borders — military movements, road repairs, etc.?

Nothing of that sort so far. Kaliningrad is now much diminished — there used to be a very large military base there, full of weapons, but almost everything went to Ukraine, and now there are few resources there or in Belarus. Their recent military exercises passed quietly, and we do not see any new threats on the ground. But there are air threats. And I think that is to our advantage. It is good that they are flying now. We are already sounding the alarm bells and considering how to respond. At least we are investing in defence. It is better that they are acting today, rather than quietly amassing forces and then suddenly launching a troop build-up on the border and commencing combat operations. They are keeping us on our toes with these hybrid attacks.

Lithuania regularly closes its border crossings with Belarus for certain periods. After the latest volley of balloons, the border crossing ban will remain in effect until 30 November. What effect is expected?

The flow of illegal migration has already been stopped, but there remains a flow of regular migration. Belarusians enter as tourists and migrants, and we admit them, but at one point there were too many — over 80,000. It became difficult for our security services to determine whether they were refugees, members of the opposition or employees of the regime. We are in a rather delicate situation and cannot turn a blind eye, so we have somewhat suspended the flow of migrants from Belarus in general. At the moment, this border closure is related to the recent incident with the balloons. It is like a sanction against Lukashenka’s regime. Because they need to export, re-export and transit various products, it is economically disadvantageous for them if we close all the doors, so we hope they will learn their lesson.

In Lithuania, together with neighbouring countries, plans for mass evacuation of the population in case of escalation are already being developed and refined, and a system for alerting the population in case of a drone threat has been created. Are you preparing anything else — shelters, civil defence units?

Bunkers and shelters — yes, the process is ongoing. Of course, there are not enough of them; we are not Finland, which has been building all this for decades. But we have inventoried everything available so that, if necessary, we know where to send people and chaos does not ensue. There will never be enough infrastructure. What we are implementing — and I think it works — is the principle of total resistance. We see that Ukraine is defending itself because the whole society is involved in the defence. When the war in Donbas began, many volunteers and volunteer formations appeared — it was not only the regular army that held the line. We have learned this principle: relying solely on the regular army and waiting for NATO is not the answer. That is plan A, but there must be a plan B, and that plan is for the whole of society to resist. This means that we must prepare for it.

We have created a network of command posts in each district where people can register as volunteers or reservists. If trouble arises, they can be mobilised. There is also the Union of Riflemen, of which I am a member. This is a long-standing tradition; the organisation has existed for decades, and many of its members later joined the ‘forest brothers’. We have increased its budget tenfold and raised the status of the organisation. It is paramilitary, but it is perhaps similar to your territorial defence. It also assists the regular army.

And the third point — I myself registered a bill, which we passed three or four years ago — on the right of citizens to defend themselves and possess weapons. Now in Lithuania, if you serve in the army, or are registered as a volunteer or in the Riflemen’s Union, you can legally purchase and keep automatic weapons at home. This was not the case before, but now my friends and I, who have completed the required courses and examinations, can legally keep automatic weapons. Diversification of weapons is important — they should not be stored in one place. Society must be able to act independently when the time comes.

Is there a willingness to defend? Is there an understanding that escalation could actually happen?

There is both understanding and willingness. People are very supportive of Ukraine, and this has been evident since the first day of the full-scale war. Many non-governmental organisations are collecting aid, launching fundraisers — in some cases, millions have been raised in just few days. Everyone understands what is at stake, and there is a sense that 90% of people, both in parliament and in society, are on the same wavelength. Of course, there are also pro-Russian supporters, as there are everywhere. But the majority are aware and united.

Speaking of pro-Russian supporters — Ukraine faces a major problem with Russian propaganda, which finds various channels to influence society and spread fake news. How are these instruments of influence used in Lithuania?

Russian television has been completely banned since the first day of the war. Some laws have been passed (I am the author of some of them) to reduce the share of cable TV channels broadcasting in Russian, already a decade ago. This helps limit the influence of propaganda. Of course, there are new trends now — Facebook and other social media is being increasingly used for that purpose. I believe the best way to counter this is through our own opinion leaders. We have them — vibrant personalities, journalists, politicians — who promote sound anti-Russian narratives that most of society supports.

At the same time, there are also political forces that, so to speak, teeter on the edge. There is a party I would prefer not to see in parliament or government, but it is there — the far-right Dawn of Nemunas, whose representative as Minister of Culture was unable to answer whose Crimea was and consequently resigned. Of course, they skilfully use social media, create information bubbles and reach their audience — and it is difficult to persuade them otherwise. However, I do not believe there are many such people in Lithuania — perhaps a few percent — and they have no influence on state policy or the country’s direction. They remain marginalised and, for now, under control.

Regarding assistance to Ukraine — unanimity for now

For Ukrainian refugees in Lithuania, the mandatory requirement to know the Lithuanian language has been postponed until March 2026. Usually, countries strive for the opposite — ensuring migrants integrate through language. Is this some kind of privilege?

We do not view Ukrainians as ordinary migrants — they are refugees from war. Only some of them will stay in Lithuania permanently, or move on to Poland or Germany. The rest will wish to return to Ukraine, so why pressure them to integrate or learn our language? Only if they choose to. With other migrants, it is different. Those coming from Iraq, Syria, Belarus or even Russia must learn it.

Poland has already imposed restrictions on social benefits for Ukrainian refugees, and something similar seems to be developing in Germany. What about Lithuanians? Have they not yet considered Ukrainians a burden?

No, such opinions have not emerged in society yet. We understand your tragedy very well and are trying to help as much as we can. There is far more discussion here about Belarusian migrants. They too can be considered refugees from the regime, and some truly are, as they were involved in the opposition. But this issue is far more complex. With Ukrainians, it is simple — they have been left homeless or have fled shelling, so they are welcome in Lithuania.

Is there the same unity on the Ukrainian issue in the European Parliament?

In the European Parliament, everything is decided by political groups, as in any other parliament. I belong to the European People’s Party (EPP). It has 188 members out of 720 — a significant share. There are social democrats, liberals, greens, Euro-conservatives and others, and these groups are unanimous in their position on Ukraine. There are the ‘patriots’ with Orbán (the far-right political group in the European Parliament, ‘Patriots for Europe’ – Ed.) and other, even more radical groups, but they do not influence the process or decisions themselves. The EPP controls the majority; half of the commissioners in the European Commission are from the EPP, and Ursula von der Leyen herself is also in this party. It can be said that the Germans hold a controlling stake, so we should focus on them. The French and Poles also have influence, of course. We have a format of cooperation called the Nordic-Baltic Eight (a format of regional cooperation that includes Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway and Sweden – Ed.). Together we are forming a most radical — in a positive sense — bloc in terms of helping Ukraine in the war with Russia.

When the war began, Ursula von der Leyen announced a plan for Europe’s energy reset. I personally believe there would have been no war at all if Europe had not been dependent on Russian energy resources. Putin expected that everyone hooked on the Kremlin’s gas would remain silent and not interfere, assuming we had effectively ‘bought them all’. But that is only partly true. Europe woke up and the reset plan was launched. Lithuania immediately abandoned dependence on Russian energy entirely — but why? Because we have been investing in the relevant infrastructure for decades. Other countries now have to do the same, in line with the reset plan.

I work on the Internal Market Committee on the new Regulation “Phasing out Russian gas”. This is a law that needs to be implemented immediately, and I hope it will be adopted before the new year. We have taken a very tough stance — the European Commission has proposed a softer version of the regulation. My colleagues and I held talks across the groups, and many supported our tougher approach — to include Russian oil and liquefied gas in the ban, and to bring the deadline forward from 2028 to 2027. If we adopt this regulation, it will no longer be mere sanctions but binding law, and Europe could be freed from Russian energy resources for decades. Cutting off Putin’s financial flows from every side will help you win.