Russia tried to envelop the agglomeration from the northwest via Dobropillya — if, during the breakthrough toward Kucherevyy Yar and Zolote, a few mechanised infantry battalions had been thrown into that pocket, it might have worked.

But we moved Azov there with attached units and crushed those who broke through — hundreds were killed, dozens taken prisoner. The enemy failed to resupply their forces by drone, failed to turn the breakthrough into success, and didn’t manage to organise an external link-up.

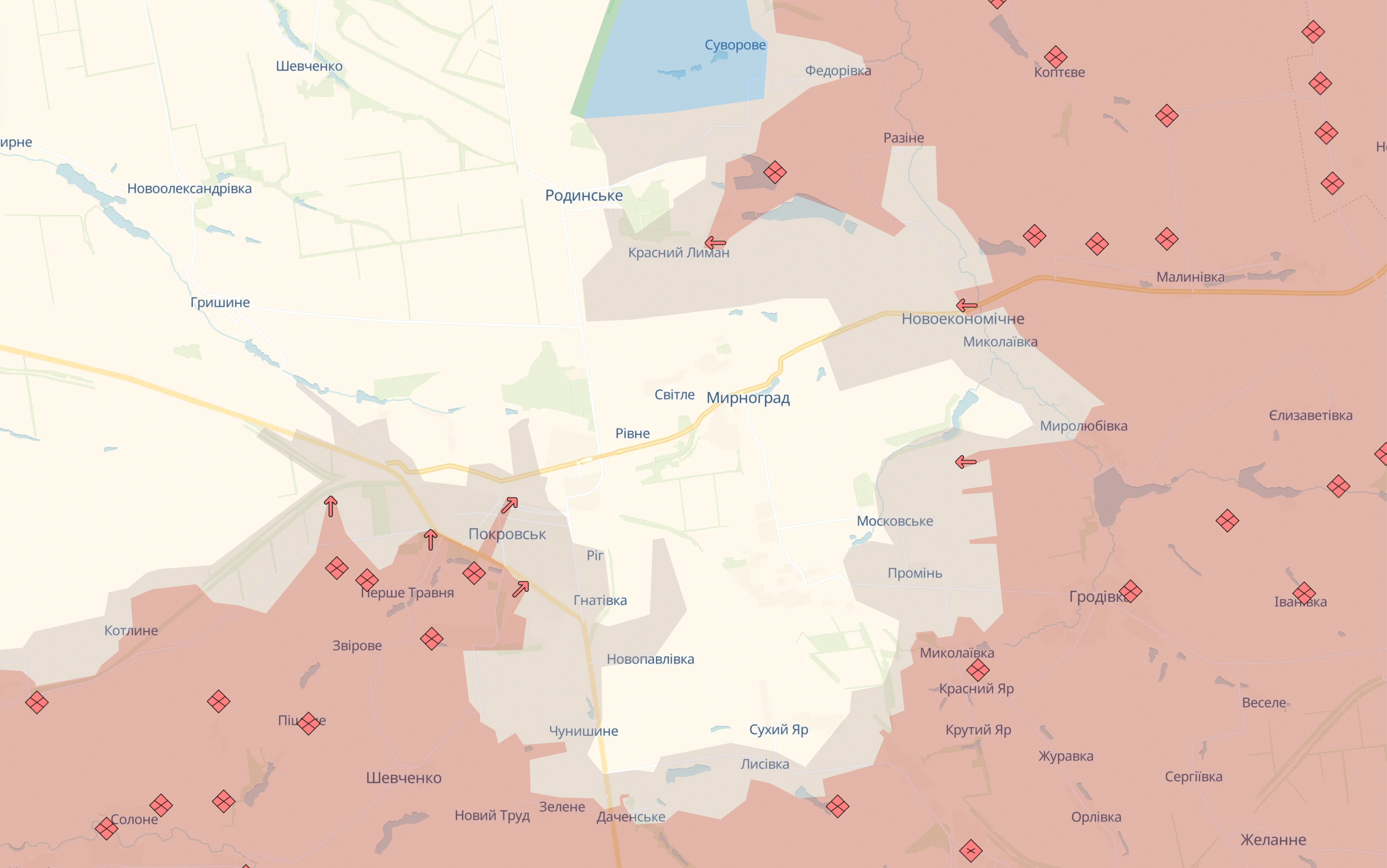

The Russians tried to drive a wedge near Myrnohrad to split the agglomeration — the Air Assault Forces are holding firm there and even manage to counterattack, despite logistics problems and the attackers’ air superiority.

Street fighting continues in Pokrovsk. Groups that slipped in from the station and the embankment are penetrating the neighbourhoods, bypassing buildings prepared for defence and setting up ambushes.

Their goal is to fragment cooperation with fire as much as possible, disrupt rotations and resupply of the defenders in the southern part of the pocket on the heights.

This is not a battalion-level breakthrough into the blocks — it’s remnants, special-operations personnel in civilian clothes, 10–20 men in a hideout per block, where they’ll be resupplied by drones.

That’s exactly why DIU specialists were committed, and the entry points were obvious — the petrol station and the furniture factory, which are on one of our logistics routes.

Probably the column shouldn’t have been dragged under FPV fire and aerial drops; it should have been put down as close as possible to the route to conduct clearance. Maybe the aim wasn’t only to hunt saboteurs but also to guarantee placement of EW systems near the town’s outskirts — to reduce drone effects on resupply.

Of course, it wasn’t just the DIU — the 3rd Assault Brigade, and various special units are also operating in the city’s blocks.

Reminder: a leaked video showing two helicopters doesn’t mean only two detachments took part in the operation.

To hunt small Russian groups we needed our own small teams — that’s all the information you need.

Right now it’s a seesaw — will we find the strength to build a perimeter around the supply line, clear the neighbourhoods and hold the pocket, or will the enemy widen the breach, increase the pressure and force us to withdraw?

Passing through a six-kilometre-wide choke point under air attack risks heavy losses. But withdrawing out into the open from dense urban terrain would also risk casualties.

At the moment it’s being decided who will spend the winter in the fields, under drone pressure, and who will be sheltering in basements.

Why are they attacking?

The Russians have more people, more equipment, and a two-to-one ammunition ratio; meanwhile we have production in the EU and US funded by the EU behind us (Moscow, by contrast, has North Korea and Iran — and third-country markets — supporting it; not for nothing the Czech president speaks about countermeasures in procurement).

Clearly, they have more sorties, more modern aircraft with at least as much flight time as ours, and greater ballistic capability.

They’ve ramped up purchases of components from China by the tens of times — and with that, UAV use has grown accordingly. Their main targets are our pilots and logistics.

Why wouldn’t they press the attack?

For anyone who really knows what’s going on at the front, it’s no secret: even systems that worked six months ago now need changing or upgrading — everything on the battlefield shifts faster than the weather.

Plus, defence is always less flexible than offence.

Heavy minefields are beaten back with line charges from breaching/demining vehicles.

Even the most secure multi-tier concrete pillbox can be breached by dozens of KABs (25 will miss, 5 will hit — and that’s enough to deal with the garrison).

You can’t cover every hideout and launch site with nets — so if you shoot, you’ll be shot back.

You can actually bury a self-propelled artillery unit in a caponier and block the entrance, but Russian pilots will toss incendiary devices there and start fires.

Evolution happens fastest in war.

The small sky is hard to control. You need lots of precision shells, cluster munitions, rocket artillery, squadrons of recon and strike UAVs to hit the Russian’s pilots.

Precision rounds and virtually unlimited GMLRS stockpiles exist only in the United States — everyone’s aware of the new administration’s policy. I’m sure there are strict limits on transferring precision weapons.

So if you couldn’t shred their antennas with cluster munitions, clear out the hiding spots, stop them taking off, or remotely block approaches with mines at the convenient points the Russian pilots use (radio-horizon points, shelters) — countering drones isn’t easy.

And when they’re already airborne above a pickup, a 50-metre shotgun blast won’t reliably drop a drone; vehicle-mounted EW struggles to keep up with frequencies — the attacker always has the initiative, so you can’t bring something guaranteed to work to the front.

It’s always a lottery: will the supply truck make it or not. That naturally has a big effect on the last kilometre — you need mines that burned up in a destroyed vehicle. Logistics suffers — the forward edge collapses.

The sky is a mess of UAVs — any drone in the air is enemy for infantry. That’s why free hunting is so popular: everyone prefers to attack where there’s no coordination between small-scale air defences, EW and supporting pilots, in the chaos of dozens of drones.

Not long ago the Russians tried to push forward positions near Mala Tokmachka equipped with pump-action shotguns, MANPADS and backpack EW systems to cover deploying columns — it turned out not to be that simple; the coordination has to be worked out. And if we see a move in real time, the drone hunters themselves can become victims.

Russia, however, has a strong combination of pilots, artillery and EW, more shells, and air-delivered iron — a third to a half of the KABs right now are aimed at the Pokrovsk–Myrnohrad agglomeration and Kupyansk — and then the infantry follow.

That’s why they’re pressing. If Ukraine had another hundred Western fourth-generation+ aircraft and at least 800 guided bombs a month, a dozen air-defence batteries, at least a 1:1 ratio in shells, expanded SBS units and companies of pilots in line brigades, we’d see a very different picture.

The fighting for Pokrovsk began more than a year ago after the fall of Selydove. Those who remember how they advanced then know how a defence collapses and a front disintegrates.

Right now we’re falling back under a hail of KABs and shells, counterattacking with tanks on direct fire, landing tactical assault forces, and still holding two district centres for a year.