Assessing the consequences of the strike based on videos posted on social media is difficult, but knowledgeable people with extensive naval backgrounds say the following. If Ukraine’s naval counterintelligence officers used a 150 kg warhead, the submarine must have sustained a breach roughly 1.5 by 1.5 metres in size. Such a hole would inevitably damage or destroy the submarine’s internal communications, systems and mechanisms. Most likely, one or two compartments were flooded.

The depth alongside the pier in Novorossiysk is about nine metres, while the submarine’s draught is 6.2 metres. It can therefore be assumed that, after taking in seawater, the submarine settled on the seabed, with some four to five metres of the hull and the sail protruding above the surface. In other words, it did not sink completely — much as we might all wish it had.

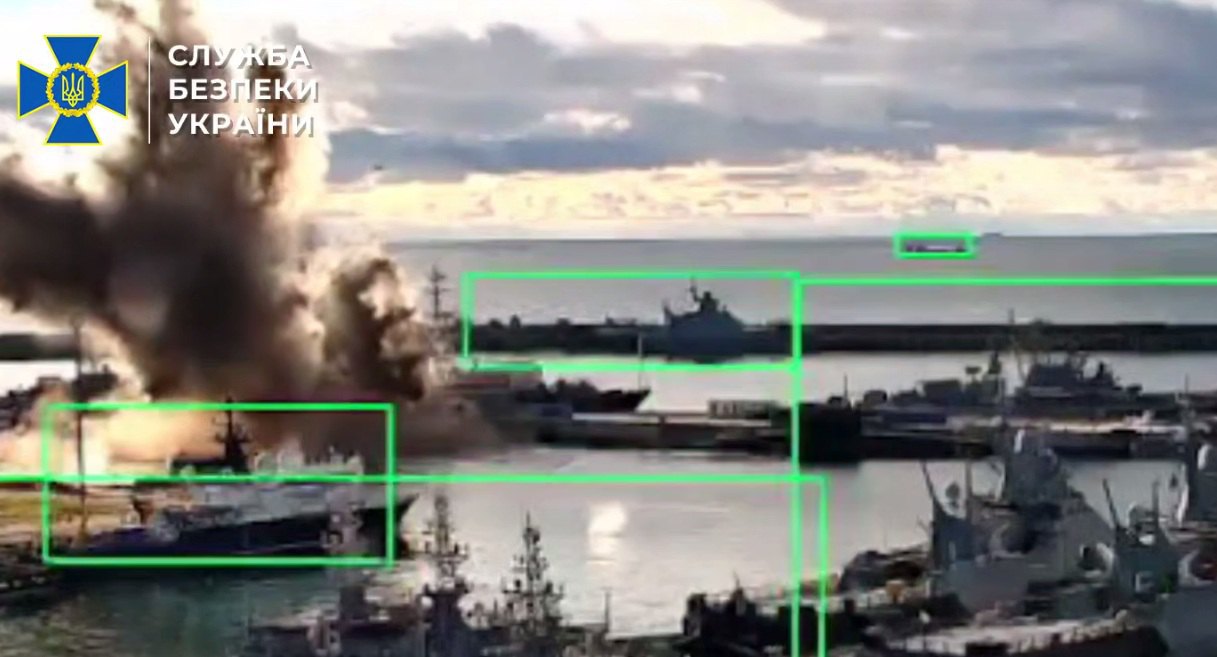

The footage shows that the explosion occurred in the aft section of the submarine, which has a single-shaft propulsion system and one main propeller. There is a view that both the shaft and the propeller were damaged, meaning the vessel is going nowhere, and repairs would be extremely difficult. In that case, it would be reasonable to expect that, following the well-established Sevastopol pattern, a SCALP or Storm Shadow missile will soon strike the already crippled submarine, removing the question of repairs altogether.

One more interesting point: the entire system for monitoring approaches to the naval base appears to have missed the approach of our strike asset, as no alert was sounded. If there was no alert, only the duty watch would have been aboard the submarine, with the rest of the crew somewhere ashore. From this, we can assume that the crew was unable to conduct a full damage-control effort. As a result, the outcome of the contest between the crew and the sea may have been the flooding not of one or two compartments, but of the entire submarine — which implies a completely different scale of repairs.

According to Stepan Yakymyak, a retired Navy captain (rank 1) and former head of the Naval Forces Department at the National Defence University of Ukraine, even minimal damage has put the submarine out of action, requiring a hull inspection in a dry dock and subsequent restoration of the damaged sections.

So what was used to hit the enemy submarine? It is said to have been struck by a Sub Sea Baby underwater drone. On their own media platforms (when they are not busy lamenting), the Russians report a new semi-submersible unmanned vessel — meaning it travels on the sea surface, but partially submerges as it approaches the target area, making detection and engagement by enemy ships and coastal assets more difficult.

In any scenario (and we are betting on Sub Sea Baby), Ukraine, relying on technological superiority, has delivered an asymmetric strike and reduced by at least 16% the number of Black Sea Fleet submarines of the Russian Navy capable of launching Kalibr cruise missiles, as well as their combined missile salvo in a single strike.

A few words should be said about the beauty of the operation — something that may escape some readers’ attention:

- the elegance of operational planning: the submarine’s mooring location was identified, the operation meticulously planned, and coordination between multiple components of Ukraine’s Defence Forces flawlessly organised. The strike asset travelled from the Ukrainian coast to the enemy naval base in Novorossiysk without losing communications at any point; the navigation system performed perfectly; Sub Sea Baby overcame the barriers at the entrance to the base, went undetected by systems designed to counter underwater threats, located the target and struck it. Without diminishing the contribution of engineers and technicians, the top honours undoubtedly go to the planners and the operators who executed the mission.

- the cybernetic beauty: let us immediately discard, as laughable, the idea that the Novorossiysk port administration themselves provided the video to the Ukrainian side. That leaves only one conclusion: our cyber unit either gained access to the port’s CCTV cameras or hacked the entire system outright and streamed the strike live. This has not happened before. A round of applause for Ukraine’s cyber units.

The moral of this naval episode: the SBU’s Military Counterintelligence and the Ukrainian Navy have pushed the enemy’s submarine forces down to a critical threshold of their ability to conduct missile strikes against Ukraine. Having only two combat-ready cruise-missile submarines means a sharply increased operational burden on their crews. And having two boats does not mean both can be used simultaneously for a missile strike, since scheduled maintenance and repairs have not been cancelled — although, to be fair, Malyuk might cancel them, the Air Force’s 7th Brigade might cancel them, and the Navy’s coastal missile division with a long-range Neptune might cancel them as well. Sea patrols and returns to base will also take their toll.

Now let us rise to the operational–strategic level and assess the situation from there.

At the start of the invasion, the enemy Black Sea Fleet included one Project 1164 missile cruiser; submarines — six Project 636.3 Varshavyanka boats and one Project 877V; three Project 11356R missile frigates; three Project 22160 patrol corvettes (with one more arriving by the end of the year); small missile ships — four Project 21631, two Project 1239, and three Project 22800; two Project 1135 patrol corvettes; two Project 1241 missile boats; and four Project 1124M small anti-submarine ships. Large landing ships deserve separate mention: five Project 775 and two Project 1171 vessels. To reinforce amphibious capabilities in the Black Sea, landing ships from the Northern and Baltic Fleets were redeployed — five Project 775 and one Project 11711. Support and auxiliary vessels are not counted here, although they, too, have been coming under fire.

The greatest evil lies with the cruise-missile carriers. The list of perpetrators — by name: 4th Independent Submarine Brigade (military unit 95200): B-261 Novorossiysk, B-262 Stary Oskol, B-265 Krasnodar, B-268 Veliky Novgorod, B-271 Kolpino, B-237 Rostov-on-Don; 30th Division of Surface Ships: Admiral Grigorovich, Admiral Essen, Admiral Makarov; 41st Missile Boat Brigade: Bora, Samum, Orekhovo-Zuyevo, Ingushetiya, Graivoron, Vishniy Volochyok, Askold, Tucha, Typhoon. In February 2022, the combined missile salvo of this pack amounted to 104 3M14 Kalibr cruise missiles.

After the Defence Forces imposed what might be called kinetic sanctions in December 2025, the total salvo dropped to 76 missiles, and taking into account the actual combat readiness of the launch platforms, to 50–60 missiles.

Ukraine — effectively a state with a navy but without ships — relying on technology and the ingenuity of its military, has reduced the strike capabilities of the enemy navy by 29%. Destroyed assets include the missile cruiser Moskva (hit by Neptune missiles), the missile boat Ivanovets (struck by a Magura USV), and the small missile ship Samum (hit by a Sea Baby USV). Damaged vessels include the missile frigates Admiral Makarov (hit by a Sea Baby USV) and Admiral Essen (hit by Neptune missiles), the submarine Rostov-on-Don (hit by a Storm Shadow missile), and the small missile ship Cyclone (hit by an ATACMS missile). Add to this list one more enemy submarine, discussed above.

In battles against Ukrainian technologies, the enemy fleet has lost its only missile cruiser, two of three missile frigates, two of six submarines (with two more undergoing scheduled repairs), one of two small missile ships, and one of six missile boats.

Russian army has effectively lost half of its ability to carry out missile strikes against Ukraine using what remains of its Black Sea Fleet. And we should not forget that cruise-missile carriers are not designed solely for that purpose — all their other missions have gone down the drain as well.

Now a few words about the enemy’s amphibious assault capabilities in the Black Sea, since we keep hearing fairy tales about a “naval landing operation” and “landings in Odesa and Mykolayiv”. Here are the facts. The 197th Landing Ship Brigade originally had seven large landing ships. To reinforce these naval “trousers” in February 2022, six more large landing ships paddled their way to Sevastopol. This did not go unnoticed: Ukraine’s Defence Forces sank Saratov, Azov, Caesar Kunikov, Yamal and Novocherkassk, while Olenegorsky Gornyak (damaged and under repair) and Minsk (damaged and under repair) were also taken out of action. In other words, out of 13 large landing ships, seven have been destroyed or damaged — a 54% reduction in the enemy’s amphibious assault capability. Put simply, where the enemy once could have landed 4,500–5,000 marines with weapons and equipment in a single wave across several landing sites, it now cannot manage even half of that. Instead of 9–10battalions, it can field only 4–5.

Back in Soviet times, when combat scenarios were being modelled, we cadets were told that in a non-nuclear war a marine battalion on shore without air and naval support would survive for about 40 minutes. That was before Ukraine’s Territorial Defence Forces existed. Today, an enemy landing force would not even have time to buy an ice cream on the beach.

Add to this the Port Kavkaz–Kerch ferry crossing, which serves as a backup to the Crimean Bridge.

Ukraine’s Defence Forces imposed kinetic sanctions through a series of strikes in 2024 (May–August: attacks on the ferries Slavyanin and Konro Trader, fuel depots and port infrastructure at Port Kavkaz using Neptune missiles, ATACMS and strike UAVs). The rail ferry line was severely disrupted; several ferries were sunk or damaged, and the crossing was repeatedly shut down.

As of December 2025, there is no confirmed evidence that regular operations have been restored. The crossing remains only partially functional (hydraulic structures require repairs). Russia planned reconstruction in September 2025, but due to the constant threat of strikes it is used minimally or not at all for civilian transport. As a result, large landing ships have been forced to shoulder these tasks.

So we can confidently draw a big, bold cross over any talk of the enemy’s “naval landing operations”. Unless, of course, they plan to paddle in on inflatable mattresses.

To sum up: the enemy fleet has lost 29% of its ability to conduct missile strikes against land targets and 54% of its amphibious assault capability. On Ukraine’s side, zero ships were employed. Pure asymmetry.

And there, through the sea mist, the silhouette of Baba Porazka (the functional kind) rises and stares straight at the enemy.

Yes, they still have missiles, and maybe a couple of landing ships left — but doing anything meaningful with them is no longer an option. Strategic neutralisation is advancing, and the effects are cumulative.

A fine cake, indeed. But every cake needs a cherry on top. Remember when Ukraine’s Air Force hit the enemy fleet commander’s desk — dead centre — in the Sevastopol headquarters during a meeting, with two Storm Shadow missiles? Now that was beauty!