“Research on Crimea was used to support claims about the German essence of Europe, which was seen as needing to be re-Germanised.”

Matthias, could you tell us about the history of how the Crimean Tatar part of the Museum of European Cultures’ collection was formed?

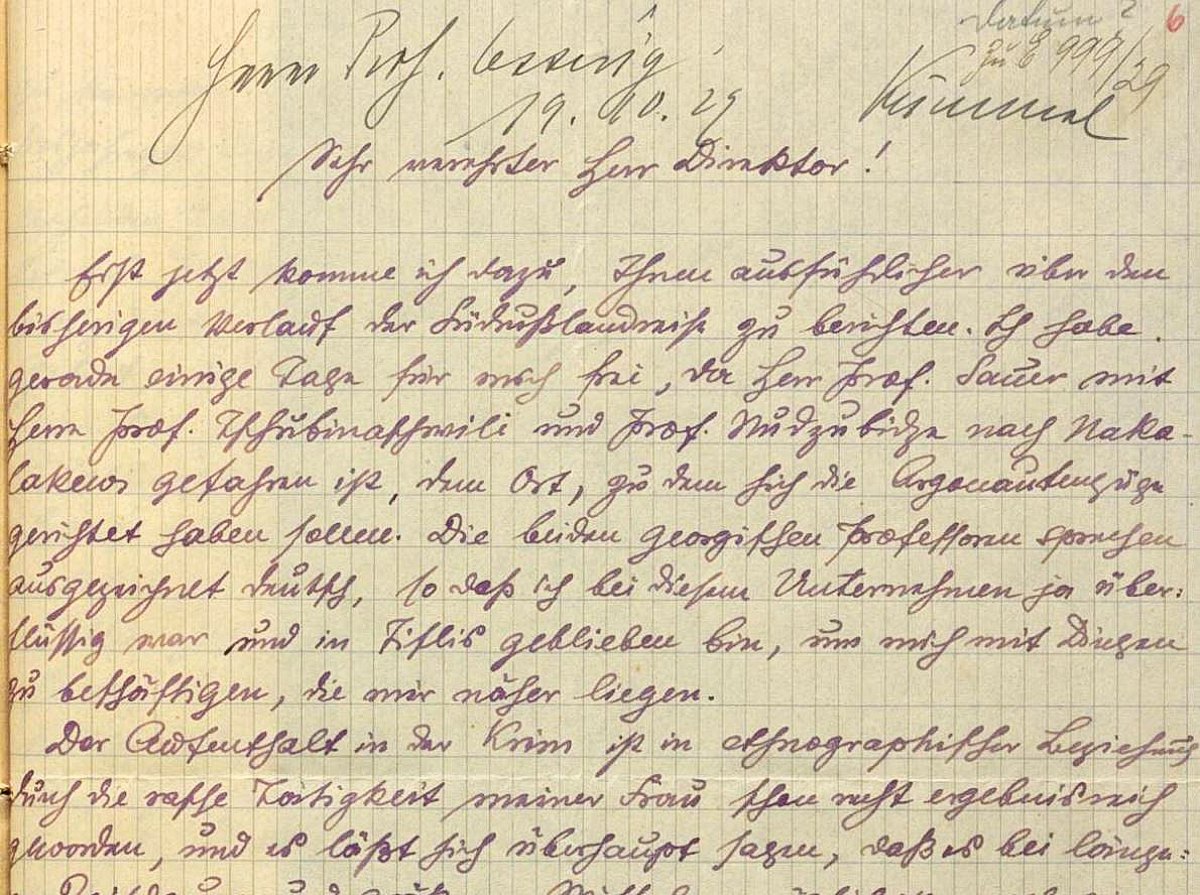

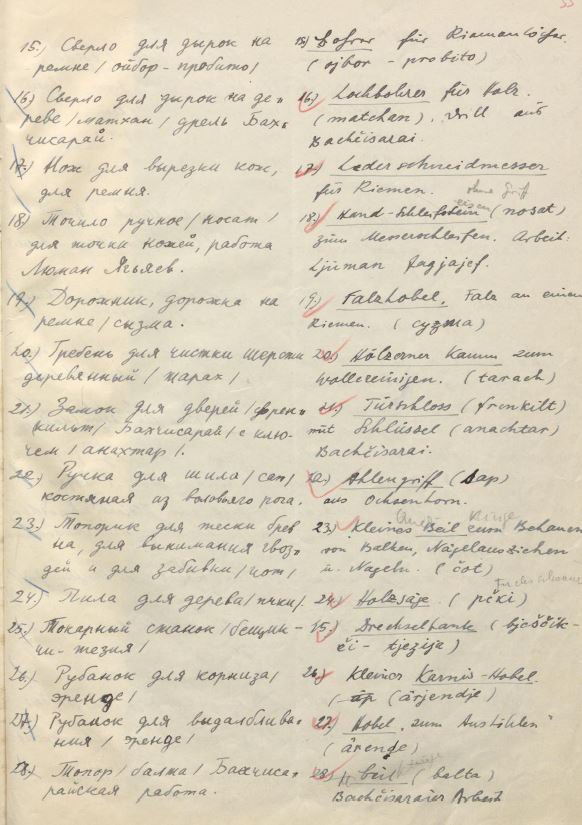

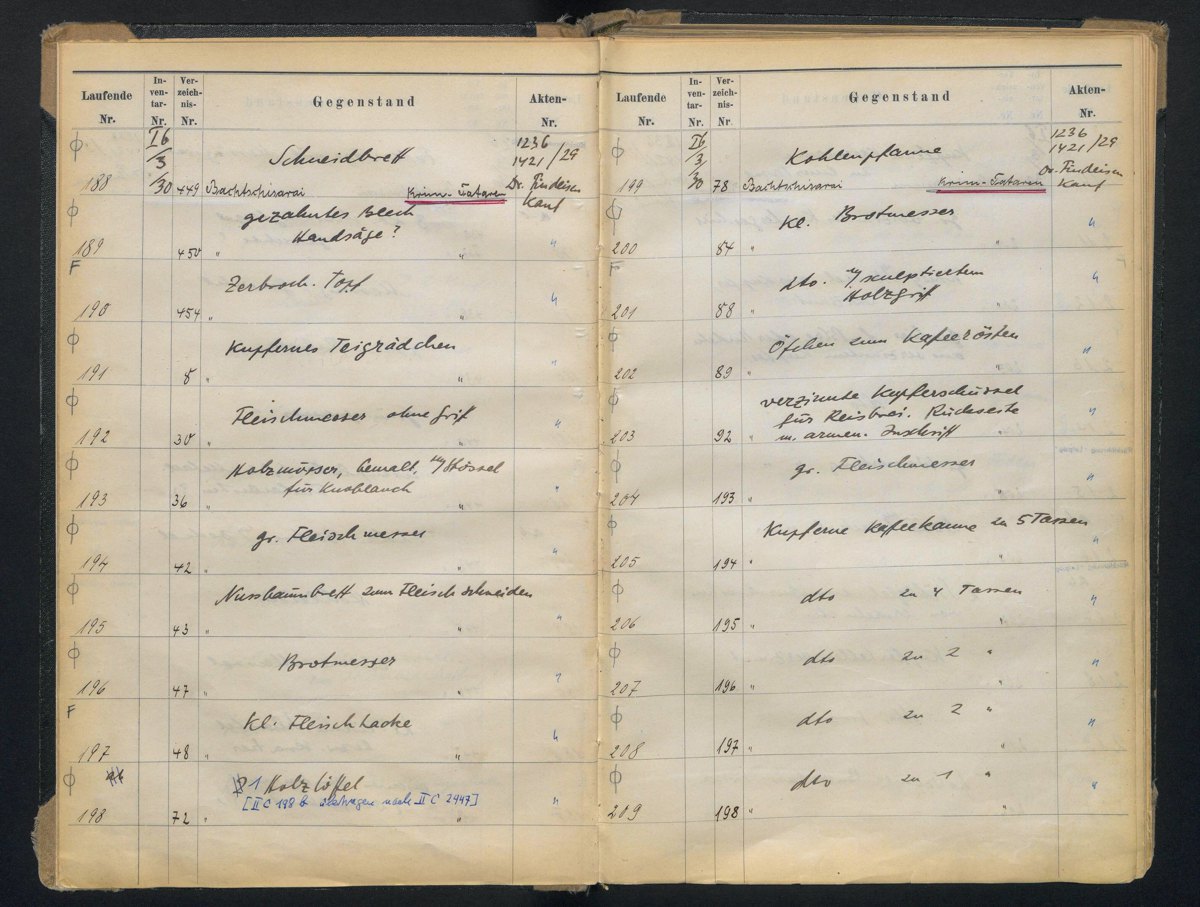

Most of the artefacts were gathered by Hans Findiesen (German ethnologist, staff member at Berlin museums during the interwar period; in the 1930s, he was a member of the Nazi Party and worked in structures connected to the SS and Heinrich Himmler’s ministry; after 1945, he tried to return to academic work and later worked as an independent researcher), together with his wife Natasha, née Mikhailova, a native of the Russian Empire. As an ethnographer, he was searching in Crimea for the Gothic roots of Germans — a focus that at the time was common in both German and Russian ethnology. In 1929, on commission from the museum, the researchers travelled to Crimea. The artefacts were acquired entirely legally, but local experts were involved in the collection process. In Bakhchisarai, they were assisted by the director of the palace complex, Usein Bodaninsky (Crimean Tatar historian and art scholar, and the first director of the Khan’s Palace in Bakhchisarai; he was killed in 1938 during Stalin’s purges). Without his help, the collection would not exist today in its current form.

In 1930 or 1931, a small exhibition was held in Berlin, accompanied by a catalogue, so some of the objects were displayed — very briefly.

I start here because this is an important remark about our collection. Today, we can reassess it and give these artefacts a new significance.

Were the museum’s collections expanded during World War II?

Yes, but not with objects from Crimea. Although a small collection did come from there, gathered by a German army officer. An art historian by training, he served in the Wehrmacht. A number of Crimean Tatar objects were sent to Berlin, but their fate afterwards is unknown. It seems these artefacts were displayed in Dresden, after which their trail is lost. They are recorded in our catalogues, but were never formally inventoried here. They may have been destroyed during bombings, as this was a relatively late stage of the war.

At the same time, regarding Ukraine, our collection was also supplemented with everyday objects from Lemko, Boyko, and Hutsul communities.

Are there moments in the collection’s history that you consider “turning points” in its institutional life?

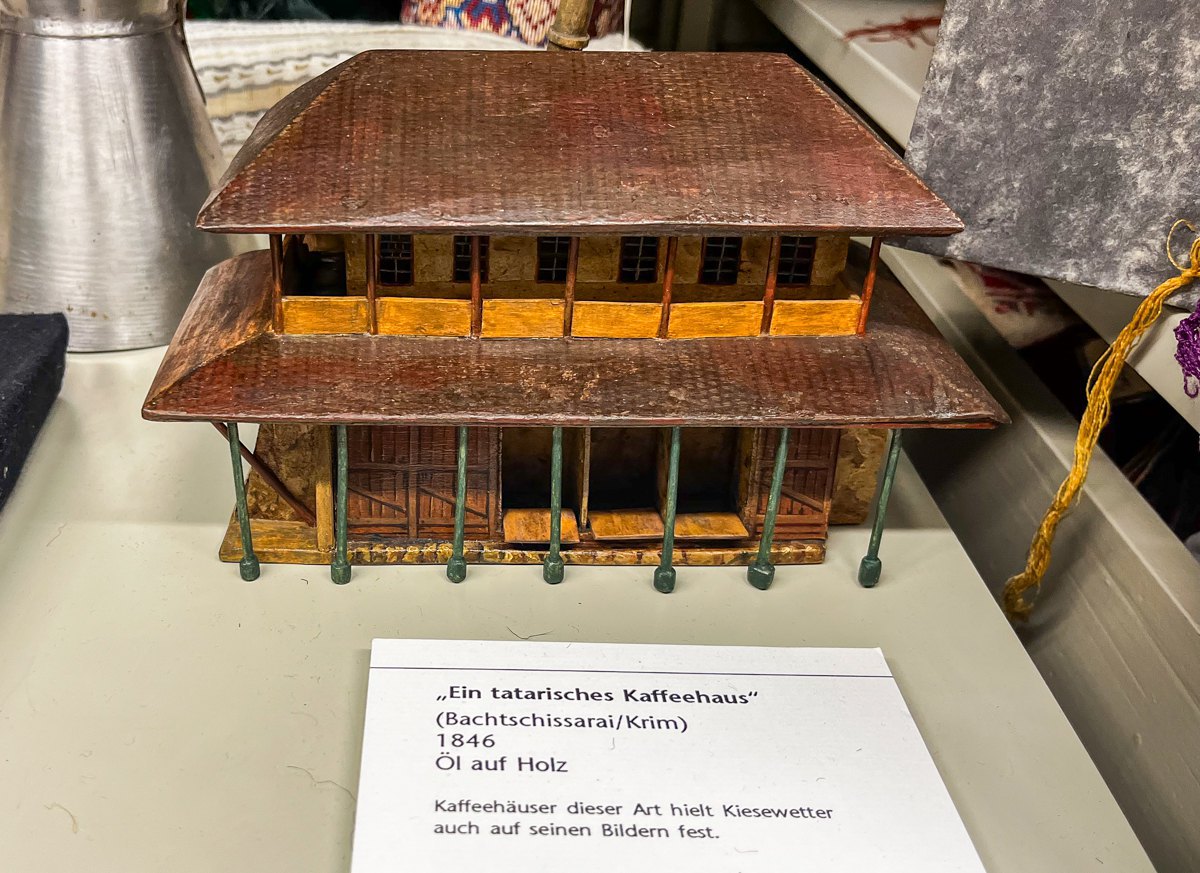

As is well known, in 19th-century Russia and Germany, Crimea and the Crimean Tatars were somewhat exoticised — a kind of “neighbourly Orient,” ethnographically interesting. And because of Crimea’s unique status at the time, as well as the partly autonomous Crimean Khanate, it attracted attention not only from Germans but also from Russians. Many Russian travellers who went to Crimea were in fact Germans serving in the Tsar’s administration. There were also intersections between German and Russian museum ethnology.

Later came the already-mentioned obsession with Germanic roots. This was heavily instrumentalised to support claims about the German essence of Europe, which was seen as needing to be re-Germanised. In the 1920s, Berlin museums were therefore keen to acquire objects from Crimea. The museum financed the collection specifically because of this interest, rather than out of concern for the Crimean Tatars themselves. This knowledge later became part of the ideology.

After conquering Crimea, the Nazis continued these studies, conducting measurements among the local population. They sought to prove that the Crimean Tatars were likely descendants of the Crimean Goths. The peninsula was treated as an ancient Germanic land, and folklore and ethnology were used to justify racial theories. Our collection carries this history, and it is important to remember it.

And after World War II?

After 1945, a different line of interpretation emerged. In fact, there was no real interpretation at all, because ethnology had been compromised by the Nazis’ claims over all of Eastern Europe. Scholars sought to distance themselves from this legacy and ignored anything that might recall it.

As a result, Crimean Tatar studies did not continue after 1945. In addition, in the USSR such research was banned at least until the 1970s. It was also forbidden to establish any connection between deported Crimean Tatars and their historical homeland. There was a very specific approach to studying the local language. The academic exchange that had existed in the 1930s came to a halt.

So political conditions had a strong influence on the scientific perspective.

In the 1990s, with the return of the Crimean Tatars to their homeland, interest in collections like ours grew rapidly. By 1991–1993, artists, activists, and researchers were coming to our museum to work with the holdings. In Ukraine, paintings by Wilhelm Kisevetter (German painter and ethnographer of the late 19th century, known for depictions of everyday life of various European peoples, including Crimean Tatars) were exhibited. More than 60 of his works are also held in our storage.

Exchanges slowed after 2014, as a number of researchers remained in occupied Crimea, and these contacts were cut off.

“When people say that Crimea has always been Russian, it is our duty as a museum to challenge that, because the objects we display tell a different story.”

The Berlin collection is unique in Western Europe. Why is it so important?

Much of the material cultural heritage was effectively lost in 1944 due to the deportation. People did not just leave their homes — they also left behind their cultural legacy. It sounds dramatic, but that is exactly what happened. Sources confirm — it is documented — that after the deportation, representatives of Russian museums entered Crimean Tatar homes and freely selected items such as embroidered towels, headscarves, and other objects for their own collections.

Of course, the major museums in Moscow and St. Petersburg had already been collecting Crimean objects earlier. So not all their Crimean Tatar artefacts come from this period. But some do. Yet it is rarely mentioned that museum collections were formed in this very direct, almost logical way. Entire cultures, objects, and heritage need to be rediscovered.

Has the way Crimean objects are described or presented at the Museum of European Cultures changed since 2022?

In 2022, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the museum displayed one of the rugs from the collection. However, it was made in Uzbekistan, so its origin was clear — our director knew where it came from, from whom it had been acquired, and under what circumstances it had been made. This is the only object from Crimea that was included in the temporary exhibition Motion Detector (a display in the museum foyer highlighting current events; when Russia occupied Crimea and later began the full-scale invasion, the museum exhibited this rug).

“Objects in the museum do not speak for themselves, so we have to make them speak by presenting as many perspectives on them as possible.”

Do you feel a difference between “historical” and “current” responsibility in representing Crimean Tatar culture today?

It is difficult to evaluate historical narratives and prioritise some over others. We do not want to merge them into a single story to present a “true picture.” That is not how it works. What I mean is that we want to include voices from different groups, different perspectives. But when it comes to disputed territories, like Crimea, and contested histories, confrontation with conflicting views of the past is inevitable. For instance, questions about who is the “true owner” of this land, and so on. I think it is also important to present these competing, sometimes contradictory narratives — not labelling them as “right” or “wrong,” but showing them as a kind of polyphonic vision of the past. It sounds a bit abstract — or like a very difficult task. There is also a view — which I do not share — that every interpretation of the past has a right to exist and is in its own way valid. But when people say “Crimea is ours” and claim that Crimea has always been Russian, it is our duty as a museum to challenge that, because the objects we display tell a different story. For centuries, Crimean Tatars lived here alongside other peoples, long before the Russian imperial conquest of Crimea.

By its nature, the museum has a duty to present historical truth, based on sources that confirm it. We do not block other perspectives. If someone claims that Crimea belongs only to the Crimean Tatars and that Russians have no place there, I would respond that Russians are present here just as Ukrainians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Crimean Tatars, and Crimean Karaites are. It is a multicultural peninsula. Like other ethnic groups, Russians have lived here for a long time and also contributed to Crimea’s multicultural landscape and culture. That is also important to acknowledge. But this does not justify the occupation — that is not up for discussion.

It is always problematic when someone claims to speak on behalf of a whole group. But it is not the group speaking — it is just some people asserting rights over a territory and saying, “This is ours.” I think that is always too simplistic. These claims should be countered through nuanced, well-grounded historical exhibitions.

What is your personal responsibility as a researcher and representative of the institution?

When exhibiting and commenting on objects, it is important to acknowledge that objects do not speak for themselves. You have to make them speak, primarily by presenting as many perspectives on them as possible. There is a perspective that can become our own point of view. For example, I as a researcher have no personal connection to this region. Yet, as a professional historian, I have my own perspective. There are also our partner organisations in Kyiv, where internally displaced people from Crimea perceive these objects very differently and have a different sense of their value. I can read about that, but I cannot fully experience it. When dealing with collections like this, one should at least try to encompass these perspectives.

Do visitors ever respond with unexpected interpretations of the museum’s narrative on the Crimean Tatar collection?

This collection is not particularly popular. We cannot boast that people come every day asking about the Crimean part of the collection in storage. But I think for the German public, 2014 really marked a turning point compared to earlier times. Before that, there was hardly any awareness of Crimean Tatars. When people saw these artefacts, they would say things like, “Well, okay, that’s the Orient,” or, “Interesting, well, a Muslim culture, probably the Middle East or Turkey.” Asked, “Is this European?” — most would have said “no.” In my view, that perception has changed. Alongside that, there is now public awareness that Crimea has a Muslim and indigenous community.

Museum of European Cultures (MEK) — a museum within the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, dedicated to the history and everyday culture of European communities.

After the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and especially following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Museum of European Cultures increasingly received inquiries about the Crimean Tatar part of its collections. Despite regular interest, this collection had rarely been fully exhibited (apart from a brief 1930 exhibition) and remained in storage for a long time.

In response, the museum began a more detailed study of the collection and intensified collaboration with Ukrainian partners. Contacts were established with the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in Kyiv and the NGO Alem, which works to preserve and update Crimean Tatar cultural heritage amid war and occupation. Curatorial work on the Crimean Tatar collection at MEK is carried out by Matthias Thaden and Sofia Botvinnik. The museum plans a dedicated exhibition project for this collection at the end of 2027.

The Territories of Culture project is produced in partnership with Persha Pryvatna Brovarnya and is dedicated to researching the history and transformation of Ukrainian cultural identity.