Franz, could you please tell about your studio Franz Reschke Landschaftsarchitektur? How did you start your practice and which types of projects are you focusing on now?

I have been running the studio Franz Reschke Landscape Architecture since 2010. I started the practice in Berlin because I studied landscape architecture there. Right now, there are about 15 people in the company working with different topics, on different scales and in different contexts, both with rural landscapes and urban environments. We have projects in different countries, but most of them are situated in Germany. The first design that was ‘ours’ was the one made for the competition in Lviv in 2010. It's still one of the most relevant projects and also highly important to both us and me on a personal level. Recently I was preparing for a lecture at the university and reviewing nine years of the studio’s practice. My colleagues and I realized that the Square of Synagogues is one of our smallest projects regarding its scale, but this doesn’t say much about its value.

You mentioned that you have projects in different countries outside Germany. Could you please reflect a bit about your experience in working with new/unknown contexts and across distances?

We are currently working all over Germany, but also in Switzerland, Austria, Sweden, and in Ukraine. We’re aware that we never know the sites as well as the locals or our clients. But we think that the distance allows us to remain on a more conceptual or even abstract level, and not just solve problems. Therefore, we think that distance can even become an advantage.

In addition, I think the distance brings a little bit of discipline. As architects working from abroad we aren’t available all the time. Less meetings with the clients also mean more ‘focus’ on the important topics. We also think that cooperation with local planners is a good way to resolve the questions arising during the process of realisation. From the other side, I like to travel and for me this is an advantage of the work — to have the chance to travel to Lviv, to Basel, to other cities and countries.

Regarding the design process for sites that we don’t know, and related to new topics, it most often looks like this: At first we do not immediately start drawing, instead we read about the site and its context and history. Together we discuss what we found out. Then we start drawing, bringing together the fragments of our thoughts. Even during the final stages of designing, we are still reviewing whether the story is ‘consistent’ or if we are losing something along the way. Regarding the topics: we often work with complicated sites that have different problems, like the site in Lviv — with its long history, its tragedy, its absence. Such tasks are difficult but also motivating.

Your project for the Space of the Synagogues is very sensitive to the context of the city. However, would it be correct to say that you learned about Lviv through the prism of Jewish history?

FR: I didn't have any knowledge about the city before — it came with the project. Each time I come to Lviv there are still intense phases of learning about the details of the site and the city. We started with a little bit of distance and not knowing a thing, but afterwards we got to know more and more.

I would like to bring up another example of experiencing the city from a distance. In their book “Lviv — City of Paradoxes”, a group of Dutch researchers and photographers called the architectural legacy of Lviv a “heritage without memory”. After WW2 Lvivians inherited a physical structure, but not always with preserved memories. Might I suggest that with the Space of Synagogues you faced an even more complicated task: to preserve the memory of Jewish heritage that is not even physically present. How did you interpret this in your project?

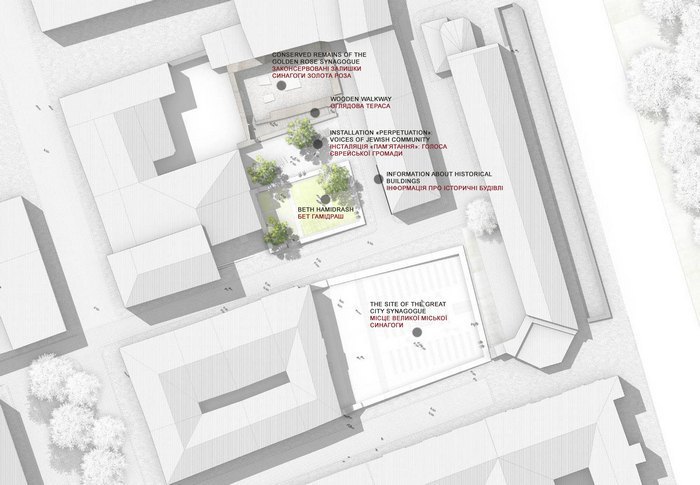

I think that different disciplines find different approaches to the same task. As architects, we base our concepts on space and atmosphere. In Lviv, we worked with the fact that there existed three Jewish buildings that were destroyed, and right now there are still three fragmented spaces within the memorial site. Our intention was to make them readable as a coherent whole, but also to preserve the memory of the three different and individual former structures. There are authentic ruins of the Golden Rose Synagogue, there is a block that defines the position of the Beth Hamidrash House of Learning, and there are summer grounds of restaurants on the site of The Great City Synagogue. They are almost invisible, and therefore we wanted to strengthen their atmosphere, making people feel that something is missing there. We decided to use the emptiness as an almost painful moment that one could experience in contrast to the beautifully paved old city of Lviv. That was our intention — to show that in the old Jewish quarter something is missing. The authenticity of the ruins of the Golden Rose was something that we wanted to protect and make understandable, therefore we provided the wooden deck, both accessing and protecting the ruins at the same time. The site of Beth Hamidrash, as the site of the former school building, became a mediator: a space of dialogue between people, between visitors and neighbours, different generations and cultures. We decided to turn it into a green space with a light roof of trees. All together the design makes the missing buildings readable again without any reconstruction.

The Space of Synagogues is both a memorial and a religious site, located in the busy city center. How did you solve the challenge of inscribing it into the contemporary urban landscape, with its consumer and touristic spaces? How did you envision the interaction between the site and these processes that are taking place nearby?

When we were doing our first preliminary study about our project in 2011 or 2012, one part of it addressed the surrounding area and the private interests in these sites for example the café, and the possible temporary commercial use of the space for events. We recommended to avoid or to forbid this kind of usage. Normally we propose making some restrictions regarding colors and design during commercial usage. In this case, we recommended not to allow such activities at all.

What is happening at the moment is the absolute opposite. Everywhere you go in Lviv, you have the same shops and the same commercial use of public space. Unfortunately, you also have them here, directly on the Space of Synagogues site.

—

I still hope that the municipality together with the city community will work this out and learn how to deal with it. I’m not sure if I answered your question precisely, but I really see this issue critically. If somebody is sitting and laughing there — it’s not a problem, if somebody is jumping over greenery — it’s not a problem either. But I’m very sceptical about commercial activities on the site or directly nearby. This would generate an atmosphere of ‘ordinariness’.

As you mentioned, there are many local challenges, but the message of the memorial is much wider. Which target groups did you keep in mind while designing the site?

FR: Basically, we expected a certain interest from the people who come to Lviv for sightseeing. They would find out from the tourist signs about the Jewish quarter and the Space of Synagogues as a memorial site, and then get acquainted with Jewish history in Lviv from the information boards that Sophie Jahnke is currently working on. Maybe those elements could also help people to understand that this is not an appropriate place for drinking alcohol. The other very important group are those whose everyday life is connected with this site, those who are living nearby or who are passing the square. We also tried to make the memorial site usable for events related to Jewish culture. At the same time, one of the most important tasks for the design was work carefully with the existing situation and remaining historical traces. That’s why we decided to make a wooden deck next to the Golden Rose, and that’s why we decided not to dig deep and not built a new building or reconstruct.

You mentioned about information boards. Could you please tell more about Perpetuation memorial installation? How did your cooperation with the Sophie Jahnke Studio start?

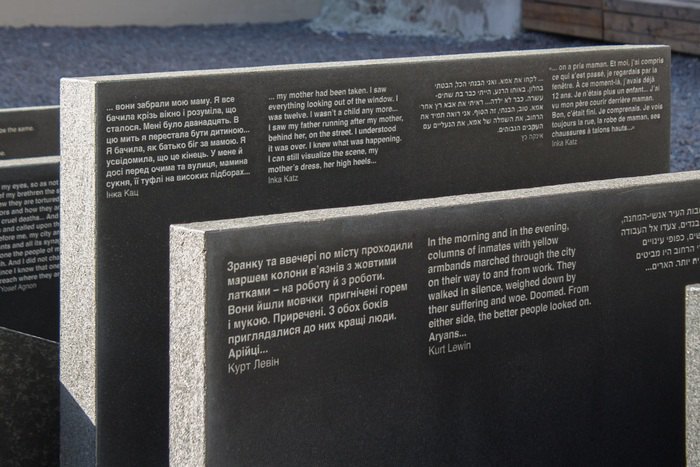

FR: During the project we proposed to have installations with information, but we realized that as landscape architects we could not achieve this on our own, and we needed somebody as a partner. So we began communication with Sophie Jahnke regarding this topic. Sophie has been running her office in Berlin since 2007, and she was already collaborating with landscape architects on the topic of memorials. Everyone from GIZ (German Society for International Cooperation – ed.) and from the city council of Lviv was open regarding her participation in the project. It was a long process of developing the Perpetuation memorial installation. It’s really half her work and half ours. It is always difficult, but we are learning to understand each other. Since Sophie is a designer and we are landscape architects, there could be a lot of misunderstandings. However our cooperation is positive, and I appreciate Sophie’s different views on things and her preciseness — for example taking 8 hours to write half a page of text (The installation texts contained quotes from memoirs, diaries, rabbis' books, thinkers, historians, writers, and city dwellers related to the Jewish community – ed.).

You mentioned that the Space of Synagogues is the project with smallest area that you have worked on, but is it the most long-lasting one?

Yes, and I think that taking such a long time for development is good for design. As a starting point you have the decision to take part in the competition. Afterwards you’re working for two or three months on the concept, and handing it over to someone who is judging it. Then maybe you will have the chance to work on this project in its full scope for the next 5 or 10 years. But with landscape architecture projects it is always like this: it takes time to grow, time to take a bit of patina, time also to be understood. So, we think the design for the Space of Synagogues is durable due to its simplicity.

Are you content with the result of the first constructed part of the memorial, and the way the design actually performs?

On the whole, I am content. I think there were many people contributing a lot. Colleagues here in Lviv and in Berlin. Also, the gardener who did the green elements, the construction company who completed the works, and the company that provided such high-quality concrete, team of researchers and managers from the Center for Urban History, L’viv architects, who adapted the project in accordance with the Ukrainian legislation. Everyone who was involved did really good work. It differs from other projects, where people only care about timing and budgets. Here it was about the quality.

I could name two or three details, which, I think, are not optimal. For example, the trees. At first, in the competition we proposed Salix trees, but it was not possible to have them here in Ukraine. So we ended up with Gleditsia. It has bright green leaves and a light habitus. We proposed five trees in the design, but in reality it ended up with three, because it wasn’t possible to get more (from Poland). During the second part of the project, we would like to return to this tree topic again.

The other thing is about the partial misuse of the space, but this is something you cannot foresee in the design.

And what is the conceptual framework for the second part of the memorial? How do you plan to design the emptiness?

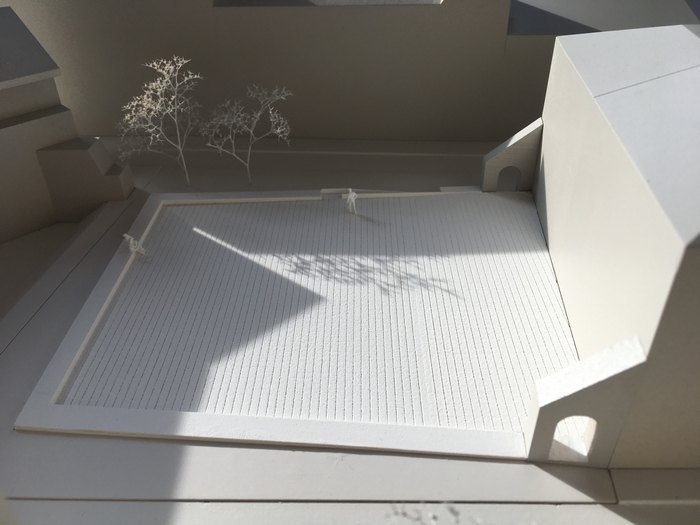

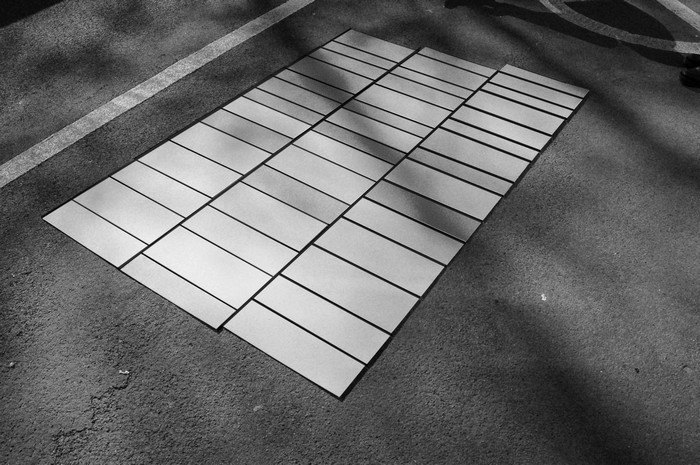

FR: In our competition entry, we proposed emptiness as a key concept for the space: there should be no vertical elements, just the frame created by the walls of adjusted structures and water running over the surface, visualizing the outlines of the non-existing building. This main idea resulted in the design of the massive surface. Such surfaces need to have some sense of scale; therefore, in the competition entry we proposed to use large concrete slabs — 2m by 2m, or 3m by 3m. They were going to be white and “empty”, and would look different to ordinary squares you can observe everywhere in the city. Of course, such elements would be complicated to produce. At the same time, we proposed a special surface that similar to transparent paper, would show the traces of the former building. And the material for the surface is something that we are still looking for. Its probably not going to be concrete, but a natural stone. Moreover, we took into consideration the aging of the materials. We will consider how this project will age, and how it will look after 2, 10 and 30 years — that’s a very essential thing.

For the moment, we have decided to go small with the format of the slabs. So according to the most recent idea, the surface is fragmented and could be perceived almost as an interior surface: small elongated elements of the surface will become the basis of the design for this part.

In addition, we will answer the criticisms of locals regarding the complete emptiness of the square by adding some trees. We propose two to three trees to the south that will bring some shadow to the sitting areas along the outline of the square. Such a vertical frame for the square will emphasise the emptiness inside the frame. And I think that the addition of the trees might bring a larger audience to the memorial.

Usually you start with the most striking design as we did in the proposal for the competition. Now we are making some adaptations and changes, and therefore the design is still striking, but more accessible.

And returning to the first constructed part of the project — it became a “Building of the year” on Archdaily, and was nominated for the Mies van der Rohe award, which considers projects that have positive social impact and contain technological and design innovations. I would say that such nominations are important as an additional way to communicate the message of the memorial. But what do they mean personally for you?

The project was nominated, and we submitted it for consideration because we thought that “yes, this is something you do your work for”, but also because we were indeed thinking about the social importance of the project in addition to the design work itself. Also, we thought that today everybody is planning trips based on digital sources, so maybe such nominations or awards will be helpful, especially concerning architectural tourism. I think this is important, because such awards provoke a discussion, some articles are written, etc. With time I realize that architecture is much more than nice pictures.

And the last question: what did you as a studio learn from the project in Lviv, if you did indeed learn something?

I think we did. For example, we learned to develop and discuss details, whilst thinking about the larger context and problem. That was something we faced when we were challenged by the question — how could we “detail the emptiness”? Based on the concept of emptiness there should no added details. Taking this literally, the space would have become mundane and brutal. So we moved more and more towards subtle details in an empty space.

And one other thing — we learned that we could really enjoy the enthusiasm of clients, partners, and colleagues in the office. Not every project can offer that. It’s a bit different from the normal way of working, it’s something more personal. Generally, I think, most colleagues in the office are, in a way, very involved in the things they do, and we try to go a bit beyond and deeper than just solving problems.