Back on the 13th... I mean, not on the 13th, but a couple of days after they had gone under radars, I understood everything. But man is such a creature that he always clings to hope. Even the smallest, the most ridiculous, even the tiniest bit of hope. Especially when it comes to the people closest to you.

We looked everywhere for him.

Especially among the POWs. In lists, without lists, in all sorts of ways.

"He is a well-known journalist, he was in civilian clothes, with a camera, it is illogical to just kill him. He could be exchanged for a whole bunch of Russians!" I kept telling myself.

"From this area they took people to Homel [Belarus]. Hospitals, prisons, you have to look everywhere," said his ex-wife and my dear friend Inna.

We were looking everywhere. Through every possible channel. And the impossible ones too. It was Inna who gave me the idea: the ROC [Russian Orthodox Church]! "Sonya, you used to go to the MP [Moscow Patriarchate], let's get the priests involved." We did it (we even found some "high-ranking" (God forgive me) priests in Belarus, who volunteered to help). To no avail.

***

When Moshchun was liberated, a sweep of the area began. This is how it became known that our Max Levin had been killed.

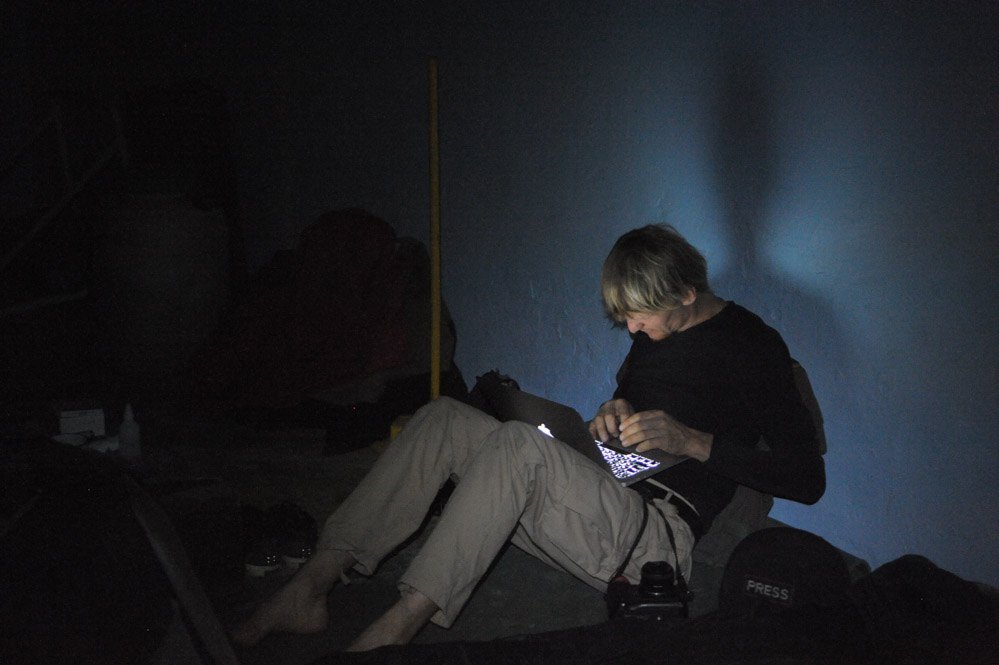

He was, I repeat, unarmed, in civilian clothes with a camera in front of him and had the "Press" label.

He was killed by two shots. In the middle of the woods.

That is, they knew exactly what they were doing. They just shot an unarmed man.

***

We had worked together for ten years.

As editor-in-chief and journalist, as two reporters.

And even when Max said a few years ago that he wanted to take some time off and then to graze freely, we still remained close people, we kept in touch, he often came to the editorial office, we celebrated holidays together. Especially birthdays. His was on the seventh of July and mine on the eighth. We loved this tradition of ours.

I am proud that people have been working at LB.ua for years. There are those who have been there since our Day One – for 13 years – and even if things change, we are still a family. All of us.

***

There have been many, many things in those 10 years. The memories are endless, but for some reason there is one totally non-work-related episode.

I gave birth to Ester on 23 May 2019. Naturally, like every mum, I wanted a picture of the discharge from hospital. But I wasn't ready to invite an outsider, it is a very intimate moment, in my opinion.

I hesitated for a long time (I don't know how to do it for myself, especially not for work), but I still decided to ask our Maxes - Levin and Trebukhov. And guess what? They had an argument over which one of them will do it. God, how I love you both, my good people.

I still can't talk about Levin in the past tense. To avoid an off-the-job conflict, it was decided that Levin would film the discharge and Trebukhov will cover the christening afterwards.

So.

The joyous event was celebrated in the park of Pushcha-Vodytsya, in a private maternity hospital nearby, where my daughter was born; champagne was not welcomed at the discharge, and we wanted to skip the formalities and just be together, all of my near and dear: my family, my Oleg Bazar and his wife Sveta, two girlfriends (journalists, of course) and Max.

I will always remember this picture...

You know, it's a still image that sticks in my mind. I'm sitting on a bench, and Max is standing across from me. He has the thick May greenery behind him, with the sun shining through, and his whole figure seems to glow. I think I can even remember what he was wearing – his favourite cotton T-shirt, which his sons had "painted" with bright palm prints – he loved them, he loved them so much. Rarely, for a man, does parenthood play such a role. In that sense, Max was an example to many.

He had four sons (three at the time), and he told my mother: "How lucky you are to have a girl. I really want a daughter too."

"You will have one, Maksym. Of course, you'll have a daughter too," my mother answered.

Not any more, alas.

For me, Max will always be standing in that park – in the sunlight glow.

***

However, there are plenty of work-related episodes too.

For example, it's late evening on 18 February 2014. Max and I are in the editorial office, I am finishing writing about the events of that black day and then I want to rush home to get a charger. I live 15 minutes away from the editorial office, in the centre of Kyiv, and I urgently need this charger.

"I'll dart to home and be back soon," I got up from the table and pulled on my black, tire-smoked down jacket.

He stood in the doorway of the office.

"You're not going anywhere!" he barked suddenly.

Very harshly. Such a tone was not common between us.

"Are you crazy?" I sat down. "What do you mean I'm not going? I need to! Why are you telling me what to do?"

"You're not going, I said. There are titushkos [hired heavies] everywhere. Stay here."

"Maksym!"

In a second, he realised that he must have overreacted and I was about to do it my way, so he backed off: "All right, I'll just charge up, change my card and we'll go together. We'll see what's going on."

"Oh, well," I was somehow confused and agreed.

So he is back after half an hour. A damn half hour.

"Sonya. Veremiy has been killed on the Volodymyrska corner, near the Black Pig [café]."

"What do you mean, killed?!"

"They dragged him out of the car and killed him."

We looked at each other, and he walked out. The episode was never discussed again.

On 18 February 2014, Max very likely saved my life. My traditional route from home to work and back runs through this intersection. If he hadn't barked at me then, at the moment the titushkos were committing an atrocity – right on the minute – I would have been there. And who knows...

***

Apart from his incredible professionalism, all his reporter qualities, Max was a very kind and easygoing person. He was quick to find common ground with anyone, but I can't say that he was quick to let anyone close. But if he did, it was for good and for a long time.

We had that kind of chemistry. I think this is largely because reporting runs in our blood. Birds of a feather fly together, you can feel it. That's how animals unmistakably identify "their own" even at long distances. It was important for both of us to be at the heart of events. To be the first to record everything. But while I always preferred politics, behind the scenes, and untangling "palace intrigues", Max was invariably drawn to the "fields".

"You will let me go to Donbas again, won't you?" he used to come begging for another business trip.

"You just arrived the day before yesterday!"

"Well, there's this and that to take pictures of... (nothing much was really going on there, it just felt good)."

"Maksym, well, this is a parliament week. Rallies are announced, plus we have four interviews. And a round table. We have to work in Kyiv."

"Trebukhov and Seryozha Nuzhnenko can handle this. They will. So I'm off, then?"

What was I to answer? Except:

"At least get the money from Accounting to cover the expenses."

"Later. Later, when I get back, I've got gas money," his answer came from behind the door.

***

Besides, he had a great sense of humour – he was always poking fun at me. I wasn't offended – I had fun with him.

Let's say it's the morning of 19 February 2014 (after that episode with Veremiy, yes), we wake up in the newsroom. I am on my couch in my office, Max is in his sleeping bag in the newsroom. Apart from us, about 10 other colleagues who covered the Maidan events slept in the newsroom and had nowhere else to go to recharge/send photos or get warm.

I get up half awake, wash my face and go to the kitchen to make sandwiches and coffee for everyone. We know for sure that troops will be dispatched into central Kyiv today (then Defence Minister Pavlo Lebedev confirmed this to me on the phone. Officially. He said so: "I'm not afraid of blood on my hands. The guys are on their way.").

The newsroom is our last bastion, but there's not much food at all, especially considering guests. Max goes down to the kitchen while I rummage around.

"Sonya, while it's morning, I'm going shopping. Maybe I'll find something open. I'll get some bread, snacks, canned goods."

"Buy me some apples."

"Apples?"

"Well, I need apples."

"Jesus, Sonya, the war, what apples!"

"They are sold in small shops. Any problem?"

He brought back three kilos. They came in very handy during those black days of February.

***

Or our first work trip to Donbas.

It is early April 2014, probably. I don't remember the exact date, but I remember that armour and helmets were a luxury back then. Luxury. I got us two Fours (on condition that we'd return them when we got there) and one Kevlar for two. The latter, of course, I gave to Max. He whistled merrily as he looked at the trophies.

"You've got to be kidding me. On the Maidan we had one-liners (I didn't even want to wear a one-liner – he forced me, pulled it on and checked the clasps), but – here."

"Wait, we have a problem – there's only one backpack for the equipment. We'll put our stuff somewhere, it's no big deal, but we have to protect it. All your lenses and what have you, we'll put them in the middle, the walls are thicker. My computer will go in the side pocket. But I'm worried that if there's a shard, say, the computer's on the side. How am I going to work?"

"Sonya, if it's a shard, who would care about a computer? Now you're being ridiculous!"

"Oh, come on!"

"Well, seriously!"

And we both laugh.

We generally laughed a lot and often.

Even when we went to the front for the first time.

***

In the summer of 2014, I worked on the book, Maidan. The Untold Story. At some point it became clear: it was impossible to write it in between work trips to Slovyansk. It was either one or the other.

"Go," Max said firmly. "What you're doing is important for history. For our country. Go. Sit somewhere in the middle of nowhere and work. I'll be here on my own for now. You will then come back and we'll travel again."

I obeyed, I left.

In Ilovaysk he was without me. Managed to get out. I won't repeat the story now, but at the time I wrote a big and important text (after which I became an enemy in Mordor [Russia]. Well, no wonder). It was "In the Name of Heletey". Read it. It has all the details and circumstances.

Upon his return, we agreed that we would all get together in the newsroom just to see and hug each other, and symbolically celebrate his happy rescue. That day, as usual, I was walking to work (including through the same alleyway in Volodymyrska Street he had saved me from), so I turned onto Mykhaylivskyy Lane, about 150 m from the newsroom, and I saw Max. He was walking towards me.

"I'm going to the shop to get some juice," he says. "I bought wine but no juice, but we have a lot of people driving."

Those words were superfluous. There are times when words are completely unnecessary. We were standing in the middle of the street, just slamming into each other, hugging each other.

I wouldn't lie that it was the strongest hug I'd ever had. The strongest. And that said it all.

We may even have been standing on the carriageway (the lane is always permanently packed with parked cars and there is no space for pedestrians). I remember the desperate honking.

And it was important for us to hug. Here and now. He had escaped from hell. Right from hell. From where no-one comes back. It was important to feel that this wasn't a dream, that he was alive and here he was. To feel him, excuse me – arms, shoulders, back.

We are together again. In August 2014, death had passed us by. Having huffed enough, Max continued on his way to get the juice, and I ducked into our archway towards our office. There was a car standing in the archway. The same Infiniti of his friend Sasha Radchenko that had saved his and the guys' lives. The Infiniti's bonnet was stitched, the rear window was broken, the whole left side – the driver's side – was shot. And there was blood on the dashboard. Max's blood, obviously. And that's when I burst into tears. I burst into tears. While Max can't hear me any longer, and my colleagues can't hear me yet. I'm not allowed to cry. Especially not in front of witnesses. I'm strong.

***

We have been through a lot, a lot together over more than 10 years. Thousands of interviews, dozens of work trips, round tables, forums and friendly get-togethers. Three criminal cases (the biggest was in 2012. The formal reason was his photos. Which the Yanukovych regime tried to use to annihilate us, to destroy LB.ua. Back in 2012, yes. So much so that we were unwanted. No way. We have survived. It was very hard, but we made it).

There was his road collision with a drunken moron from Ukrzaliznytsya (I'm afraid to be wrong, but I think he was recently reappointed somewhere).

Many, many things...

Max was a very straightforward, crystal-clear and honest man. He had no tolerance for "backhand deals".

...We are not heroes. We are just journalists. By life and by blood. That's probably what's kept us together for so many years. Both entering the profession at 15. Both appreciating the thrill of what we love.

Now I will do it for both of us.

***

You weren't sentimental, snorting at all the touchy-feely, but you know how much I love you.

I will continue our work.

And I will surely avenge you.

To that forest outside Kyiv where you had lain for a fortnight.

The word is a powerful, very powerful weapon. So is a photo. Rest in peace.