"The electoral process must begin no later than six months after the end of martial law."

The Central Election Commission has submitted a package of recommendations to the Verkhovna Rada on holding nationwide elections after the lifting of martial law in Ukraine. We are talking about post-war elections, correct? It is explicitly stated there, but I will clarify this at the outset for the sake of clarity.

The Central Election Commission proceeded from the current legislation, according to which elections in Ukraine are not organised or held during wartime. Accordingly, throughout the years of full-scale aggression, we have been developing legislative proposals for post-war elections. The first package was adopted by a resolution of the CEC on 27 September 2022.

After that, we continued this work: three working groups worked on key areas. Now the work is practically complete. It is important to emphasise that we have been preparing for post-war elections all along.

The Constitution prohibits parliamentary elections during wartime, while the law prohibits presidential elections. Have you discussed mechanisms for changing this?

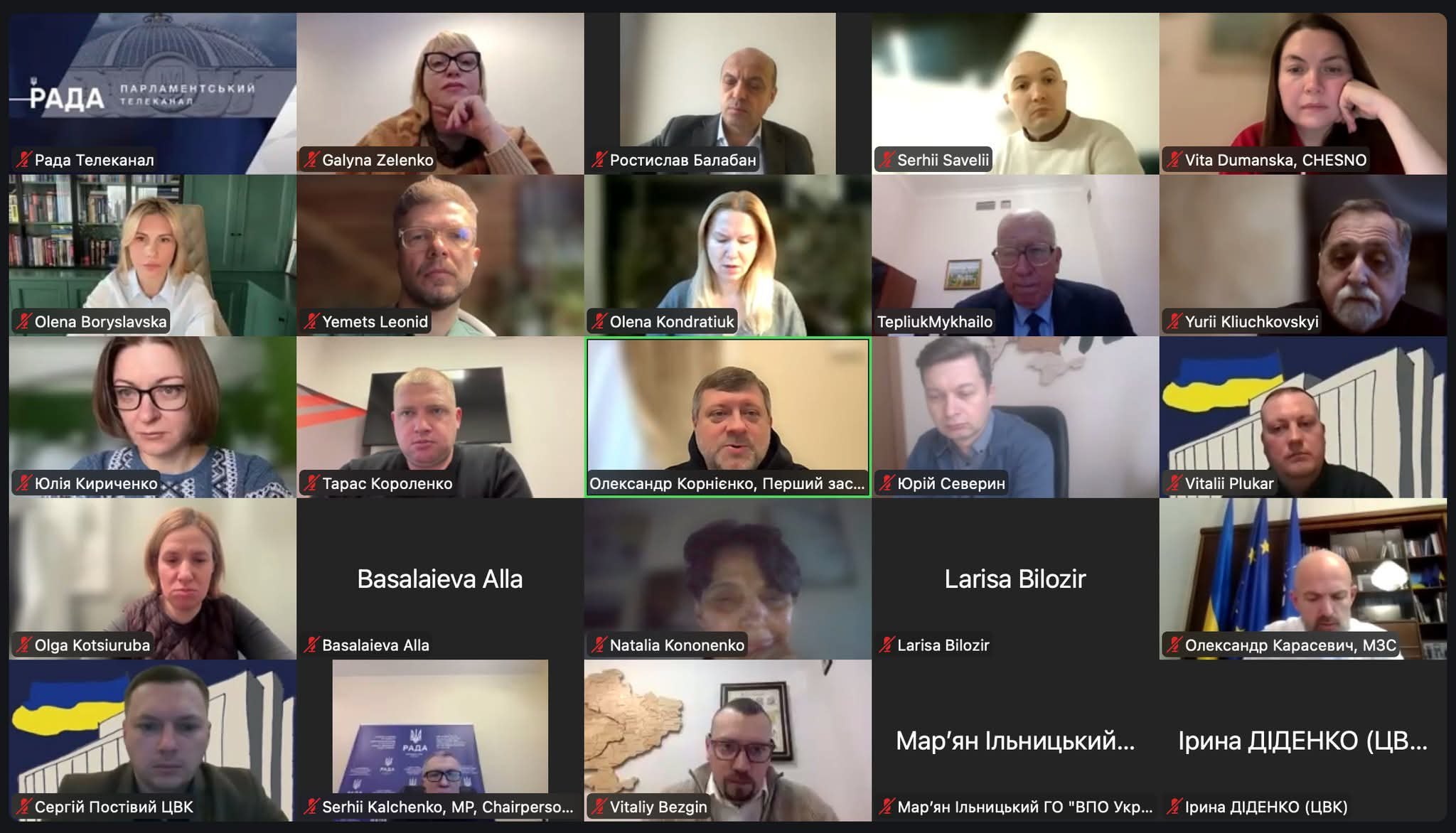

On Thursday (8 January — S.K.), there was a meeting of the working group, to which scientists and scholars were invited to present their views on this issue.

The working group consists of 62 people. On the one hand, the logic of such a format is understandable — to involve parliamentarians, the Central Election Commission, constitutionalists, and the public involved in elections. But with so many people, it is difficult to achieve a substantive result.

It is very good for the CEC that this work began within the walls of parliament. The CEC carried out preparatory work, but we are not a legislative initiative entity.

For my part, I have personally raised the issue on more than one occasion that it would be good and right for the Central Election Commission to have the law determining the specifics of post-war elections adopted as quickly as possible, as early as possible, so that there is more time for preparation, because there are many complex issues that require lengthy preparation.

Even in peacetime, electoral legislation has never passed quickly and easily through the Verkhovna Rada.

I have been working in political journalism since 2002 and cannot recall any elections that were not preceded by changes in legislation.

Me neither. The electoral system changed particularly often during parliamentary and local elections. But back then, the changes were driven by political issues.

Today, it is necessary to change procedural issues that should respond to all challenges. These are slightly different, more complex issues, so it is not possible to draw an analogy here.

For example, the decision that the Verkhovna Rada will make regarding voting abroad will affect a whole range of other actions. This may include interaction with foreign states and other changes in legislation.

You mentioned an important point, that the CEC is not a legislative body. The Verkhovna Rada, the President and the Cabinet of Ministers are the legislative bodies. And it seems that the CEC has now been assigned a function that is not its own — preparing draft legislation.

This was purely our initiative. I have already said that we began this work in the most inclusive manner possible, involving the public and international partners back in 2022.

At that time, we believed in a quick victory and hoped that the 2023 national elections would be able to take place as planned, so we were in a hurry. And we proposed the first package back then. Then we continued to deepen our work.

I have said many times and will repeat: post-war elections will be extremely difficult on the one hand and extremely responsible on the other. And the Central Election Commission, naturally, tried to use all this time to prepare. We identified the key risks and challenges and worked on them. And one of the first challenges is the existence of legal certainty, the existence of law.

I proceeded from the assumption that the Central Election Commission is a specialised body that deals specifically with elections. Therefore, it is logical that we should develop specific mechanisms to make it easier for MPs to make decisions. I emphasise: we did not touch on any political issues (such as the electoral system for parliamentary elections).

It is too early to talk about parliamentary elections.

I would not say it is too early. The procedure depends on the electoral system that will be used in the parliamentary elections. If it changes shortly before the elections, as has often been the case in Ukraine in the past, that is bad. It would be good for the CEC to understand whether the electoral system will change. Because this affects the preparations. But this is absolutely not our function. We tried to stay away from political issues as much as possible, because this line is very blurred.

In any case, we understand that since we are not a legislative body, the final decision will be made by the Verkhovna Rada. Our task is to show ways to solve possible problems, start a discussion, offer a solution, and then parliamentarians will work on it and, I hope, find the best models.

Holding presidential elections is a requirement of our American partners, and, of course, Volodymyr Zelenskyy needs to show movement in this direction. However, a number of experts believe that your current work is largely futile, because no one knows when peace will come and in what form, and by that time the conditions and positions for holding elections may change significantly. What do you say to that?

Anything can happen. We cannot accurately predict how events will unfold, especially in the situation we are living in. Everything is changing very quickly. Remember how COVID-19 made its own adjustments even before the full-scale war. It is impossible to predict everything. But we must be as prepared as possible for different scenarios.

The Central Election Commission is a law enforcement body that must enforce the election law.

If there are suggestions that the peace process could end with elections that are earlier than planned and earlier than necessary for proper, desirable preparation from our point of view, such a political decision is not made by the Central Election Commission; it is not the body responsible for making it. But the Central Election Commission must be able to implement it.

And here we return to procedural issues. We have formulated many different rules to overcome key challenges and have actually developed a draft law that, in my opinion, looks quite systematic.

I don't know if the CEC has ever taken such a comprehensive approach to legislative issues before. And most of the challenges are atypical. They did not exist in peacetime.

Obviously, one of the key challenges is the timing of the elections. You previously stated that you consider at least six months to be optimal for preparing for the first post-war elections. First and foremost, to restart the register. Earlier in the conversation, you mentioned that the elections could be expedited as much as possible, leaving perhaps 60 days for preparation. What is the shortest time frame in which the CEC could prepare for the elections? And what is the optimal time frame?

Let me clarify that I have not mentioned any specific time frames over the years. In answering this question, I have always used and continue to use the argument that the more time the CEC has for preparation, the better. But we need to find a balance so that we, as a state, are not accused of stalling for time. This should be a political decision, which the Verkhovna Rada should respond to.

As for specific deadlines, I could say that the Central Election Commission's Resolution No. 102 of 27 September 2022 mentioned six months. In addition, the memorandum of the Verkhovna Rada deputy factions and groups, which they signed in the format of Jean Monnet Dialogues, also mentions six months. The only question that remains is: six months before the start of the electoral process or before the day of voting? The participants in these dialogues gave different answers.

In the resolution adopted on Wednesday (7 January — S.K.), we set a period of six months before the start of the electoral process. Within a month after the end of martial law, the Verkhovna Rada must schedule the presidential election process.

That is, the electoral process must begin no later than six months after the end of martial law. And it will last for 90 days for the presidential election, in accordance with the current Electoral Code. This is the position and vision of the CEC.

We understand the difficulties, so it is better to have more time. When we discussed this bill, there were two options: six months before the day of voting and six months before the start of the election process. In the end, we chose the second option — there were too many challenges.

However, again, this is a political issue, and the answer must be given by the Verkhovna Rada.

If you are only given 60 days to prepare, will you have enough time?

It is difficult to say until we understand what this is about. It all depends on the procedure.

Let's assume that martial law ends tomorrow...

But what will the law be? What will it contain? What will the procedures be? What will we do abroad? Specific issues require specific deadlines. Until we know this, I cannot give you a specific answer as to how much time is needed.

I really hope that Parliament will pass a realistic law that the Central Election Commission will be able to implement, adhering to standards and best practices, resulting in these elections being assessed as democratic and in line with international standards.

"Being on the Register of Internally Displaced Persons does not lead to a change in a person's electoral address."

Let's talk about specific challenges. In the last elections, 33 million Ukrainians were included in the voter list. Today, according to the Register of Internally Displaced Persons, there are officially 4.6 million IDPs. Of these, only one million are known to be present, as they receive regular payments and are physically present. The whereabouts of the other 3.6 million are unknown. They may be registered as IDPs in Poltava, live in Uzhhorod, have gone to Poland, returned to the temporarily occupied territory, etc.

The State Register of Voters (even taking into account that it has been updated and all the data from periodic updates since the start of the full-scale war has been entered into it) is not accurate in reflecting information about the actual location of all our voters, as our citizens do not like to register their place of residence.

The IDP register you mentioned is not very helpful in this regard, as it is not linked to the State Register of Voters in any way. Being listed in the Register of Internally Displaced Persons is not the same as registering your place of residence. The electoral address is determined by the registration of residence. In other words, being listed in the Register of Internally Displaced Persons does not lead to a change in a person's electoral address.

Even if we provide at the legislative level that citizens on the IDP register can change their electoral address, it will turn out that the state will change the electoral address without the citizen's knowledge, and the voter will not be aware of this. Because even how to inform them about this is already a question.

Perhaps through the Diia?

For this to happen, they need to be in the Diia. And the registers need to be linked to each other. How can this be done? Manually or automatically? To do this automatically, you need to have the appropriate software so that the database has all the necessary information and the ability to synchronise, which is not a given.

In recent days, we have returned to this issue and included a provision in the draft law that would give the Central Election Commission the opportunity to obtain, first, the Register of Internally Displaced Persons, and second, if possible, their electoral address, and if these people have moved from temporarily occupied territories where elections are not organised or held, so that the Central Election Commission itself can change their polling place or electoral address.

We have another problem: according to the State Register of Voters, almost 7 million voters are in the temporarily occupied territories. But in reality, there are far fewer than 7 million. Many citizens have left either for Ukraine or abroad, but have not registered. According to the register, it looks like they are still there. And that is a problem. We need to find mechanisms that will allow these citizens to be transferred to where they actually are.

There is, of course, a much simpler way — citizen activism. Voters (those who do not have a current registered place of residence) must come and say, "I want to vote here," and the state must provide them with every opportunity to do so.

We have a mechanism for changing one's electoral address. It was restored and has been in operation since 1 January. One can change their electoral address either by contacting the State Register Department or online — through the voter's personal account on the website of the Central Election Commission's State Register of Voters.

Is there any information campaign about this? How are people supposed to know?

The last, third stage of opening the State Register of Voters took place on 1 January. This service is just getting started. That's one thing.

The second point is: is this the right time? The war is ongoing, with shelling, blackouts, migration processes, and here we have an information campaign about changing your electoral address.

Of course, we need this because it is one of the elements of bringing the register up to date. On the other hand, there are certain risks, such as shifting society's focus from the war to the elections. We need to find a solution on how to do this correctly. Perhaps we will prepare an information campaign, but launch it later. Or we will find forms that are acceptable for the current conditions.

So, returning to the main question, one mechanism is changing one's electoral address. The second is a temporary change of voting location without changing the electoral address, on a one-off basis for specific elections. This mechanism has also been launched. We want it to work electronically, which was not the case in 2019. As you remember, there were huge queues, especially in the last few days.

So, if we are talking about Ukraine, we want to make the mechanisms that already exist more accessible and simpler. For example, our draft law includes a proposal to extend the deadline for changing one's electoral address from the sixth day of the electoral process to 30 days before the day of voting, thus significantly extending the time frame. For TCVL (temporary change of voting location — Ed.), introduce an electronic form and, conversely, slightly shorten the deadlines (to have time to create additional polling stations based on the results of the TCVL).

"Electronic and postal voting are the most vulnerable forms of discrediting."

Eight million Ukrainians live abroad. In an interview with Interfax-Ukraine, you said that only 382,000 are registered with consulates. Most citizens do not register and will not register. According to the law, Ukrainian elections abroad are held on the same day at diplomatic missions. At the same time, the total capacity of all foreign polling stations is 250,000 voters.

Our record was in Milan during the 2014 Ukrainian presidential election, when 6,728 voters cast their ballots at one polling station. More than 5,000 people voted in Rome at that time. But this is, of course, not the figure to aim for — it is extremely difficult for everyone: both voters and commission members.

There are different scenarios for organising overseas voting. Which do you consider optimal? If you were the one making the decision.

We are lucky, we do not make this decision (smiles).

The Central Election Commission considers the issue of overseas voting for millions of our citizens to be the most difficult organisational challenge.

In terms of democratic standards for conducting elections, this is also a challenge. We had a working group, we explored options, studied the experience of other countries and approaches around the world. After all, Ukraine has a diaspora that is unique in its scale. When a country has several million citizens abroad, it is a big challenge.

The working group initially focused on three options: online voting, postal voting and voting at additional polling stations outside diplomatic missions. Online voting was immediately rejected based on the working group's analysis and information gathering. We worked a little more deeply on postal voting, but it was also not supported by the members of the Central Election Commission. We consider both of these forms to be too risky and dangerous for Ukraine, especially in the context of post-war elections and the threats and risks we face.

Electronic and postal voting are the most vulnerable forms of discrediting.

This issue is not only about complicated organisation and cybersecurity, but also about the anonymity of voting, which is clearly lost in postal or electronic voting.

Exactly. I don't know how the principle of secrecy can be ensured in online or postal voting when voters express their will. It's not like a polling station, where we have a so-called controlled environment, official observers, a separate booth, no one shows anything to anyone, there can be no influence or coercion.

If even the American electronic voting system has been targeted by Russian hackers, it is obvious that they will use all possible means against us, both propaganda and technical ones.

There are many risks, which is why the Central Election Commission has rejected these options. We have described this in general terms in our resolution and therefore propose to solve the problem of overseas voting by creating additional polling stations outside Ukraine's diplomatic missions.

First, this requires a legislative basis. Second, it requires a lot of organisational work, because it concerns not only Ukrainian legislation, but also the legislation of the host countries, coordination of processes: obtaining permits, finding premises, logistics, equipment, commission members — there are many related issues.

We began this work at the end of 2023 with the support of our international partner, International IDEA, from Moldova and Romania. We studied their experience and at the same time consulted with the competent authorities of the host countries regarding their support for us in this matter, if such a decision is made.

In different countries, we see different levels of willingness to help us, different levels of assistance, but it is almost always there: from "we have no objections, do what you want" to "just tell us what you need, we will do everything ourselves," to providing premises, and in the United Kingdom, they even asked if there was a need to help with personnel for the commissions.

In addition, during these visits to prepare for voting abroad, we always met with associations of Ukrainians abroad: most of them are very active and ready to get involved in these processes and help with the organisation. The level of activity varies, but for the most part, this is also a great resource that can greatly contribute to the deployment of additional polling stations and informing our voters abroad.

Perhaps you have figures for Germany, the Czech Republic or Poland showing how many additional commissions are needed? I am naming these countries at random — they are where most Ukrainians currently live.

We need to start with the fact that consular registration does not reflect the real situation at all. It has always been inaccurate, but now we understand that it simply does not correspond to reality in quantitative terms.

So, the first question is to find our voters in order to understand how many polling stations are needed in a particular country. It is clear that the main organisational function of voting abroad lies with Ukraine's diplomatic institutions. This has always been the case, and it remains so today. Accordingly, our embassies/consulates are the entities that will determine the number of polling stations required, and they will do so in accordance with our concept, which we have already outlined in the draft law, provided, of course, that it is supported by parliament. There are several tools available for this purpose.

We propose to introduce a mechanism such as active registration, to put it simply. The third form is to notify of one's intention to vote in a certain place — in addition to changing one's electoral address and temporarily changing one's place of voting. Before the start of the electoral process (which is why we are talking about six or at least three months before the start of the electoral process), citizens who are abroad will be able to submit an application to vote abroad through a service that will be launched at that time. A citizen who is not registered with the consulate, is not registered anywhere, simply lives abroad and has a Ukrainian passport. They submit, as we simply call it, an application for active registration, in which they indicate that they want to vote in a certain country, in a certain city.

As a result of this active registration process, we should gain an understanding of our active citizens who are responsible and want to vote in a specific city or country. This provides information on where additional polling stations need to be set up.

This is one way for the embassy to gather information about active voters. There is a parallel process where our embassies themselves know where our citizens are concentrated. In principle, they may not need active registration; they can use their own information or information received from the authorities of the host country about temporary protection (foreign states do not share personal data, but are mostly willing to provide statistical data on how many of our citizens and in which regions have registered for temporary protection).

This data may also be inaccurate, as our citizens migrate further, but it is a basis of some kind. With their own information, information from the authorities of the host country, information about active registration, embassies, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs can come up with a proposal to create an additional polling station.

How many polling stations are there now, for example, in Poland?

Five.

And a million of our citizens. Of course, minus children. How many people can theoretically vote?

82%

That's 800,000.

But we don't know what the turnout will be. How many citizens will return. How much time we will have. All estimates are very approximate. We need the law to include mechanisms that allow us to respond flexibly to changes in the situation.

How can we campaign abroad (which must be financed exclusively from election funds) and pay for political advertising without violating our legislation?

These are difficult questions. And the complexity lies in the fact that, in addition to Ukrainian legislation, the legislation of the host country will apply in each specific case, and its peculiarities must be taken into account. That is one point.

The second point, and we raised this issue in our resolution on the draft law, is that, for example, election fund accounts are currently opened in the national currency. In essence, payment in foreign currency is impossible. Even in such a seemingly technical matter, we need to think about finding solutions. How to pay for advertising even on Facebook?

In the field of campaigning, the Central Election Commission performs rather indirect functions. This is the sphere of activity of the subjects of the electoral process. Regulation — restrictions or compliance with legislation — is carried out by the National Council on Television and Radio Broadcasting.

I understand that this is a problem, raised by MPs and OPORA, of how to ensure equality. I cannot imagine how it is possible to ensure equal rights in Ukraine and abroad in terms of campaigning, if only because each country has its own legislation, which can vary greatly and contain different restrictions.

On voting in Russia and Belarus: "I don't see how Ukraine can guarantee the electoral rights of citizens on the territory of an aggressor state."

What is the main problem with voting for military personnel, who now number over a million?

The military is a priority because people who defend the country's sovereignty cannot be deprived of the right to vote and be elected.

If we are talking about post-war elections, the number of military personnel will probably be less than a million. Some of those who have been mobilised will return. But we do not know how many military personnel will remain to perform tasks closer to the line of demarcation. In other words, the number will decrease, but it will still be large and problematic.

Again, we have developed a number of proposals — the draft law contains a separate article on voting by military personnel: the general procedure remains in place, whereby they can vote at their places of deployment at general polling stations. The mechanism whereby military personnel can vote at special polling stations, which are set up at the request of the Ministry of Defence, as was the case in 2019, remains in place. It is envisaged that military personnel will be able to be included in the voter lists at regular polling stations near their place of duty at the request of their commanders.

Mobile voting is also possible, similar to voting at home, where commission members can come with a ballot box.

There is another problem with the military — observation of the voting process. Simply banning it for security reasons is not a good idea, as it could lead to accusations of abuse. Therefore, we are establishing the need to develop protocols for the admission of observers.

A somewhat manipulative question. What should Ukrainians who have gone to Russia or Belarus do? Not to mention the rights of prisoners of war. How many polling stations were there in Russia before?

Four or five. In 2019, they were closed. At the request of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Central Election Commission voted to close the polling stations. And in 2019, they were no longer operating.

I do not see how Ukraine can ensure the electoral rights of its citizens in a democratic manner on the territory of the aggressor state.

To avoid any speculation, we propose that this provision be written out separately so that it is enshrined in law.

Incidentally, the polling stations were not simply closed. Voters who were registered with the consulate and included in the electoral rolls were redistributed to other countries bordering Russia. Some were transferred to Finland, some to Kazakhstan, and so on. The state must ensure its citizens' right to vote, and it did so by changing their electoral address abroad. There is also a mechanism for independently changing the place of voting to a polling station in Ukraine or any other foreign state that is not recognised as an aggressor state.

To participate in presidential and parliamentary elections, there is a rule requiring five years of continuous residence in Ukraine. Obviously, this will be a stumbling block in parliament. What is your opinion on this?

The Central Election Commission resolved this issue in Resolution No. 102 of 22, when we wrote that a person's stay outside Ukraine during martial law does not violate the residency requirement. We have not changed anything fundamentally, we have only added that such a stay must be on legal grounds.

But this is a political issue: it is up to the Verkhovna Rada to decide, not the Central Election Commission.

I am just curious whether there is a chance for a hypothetical Arestovych to register as a candidate.

There needs to be a law that defines the conditions. And we need to look at the specific documents when they are submitted.

"If voter turnout in the referendum is very low — for example, 10–20% — the question of its legitimacy may arise."

Davyd Arakhamiya voiced the idea of holding presidential elections and a referendum on a peace agreement on the same day, which is currently prohibited by law.

I believe that this is an issue that requires a political decision.

Previously, when the question of combining elections was raised, I always replied that combining processes for the Central Election Commission and the entire vertical structure of election commissions, primarily precinct commissions, always creates additional complications and an additional workload. However, there have been cases of combining nationwide elections in Ukraine.

I do not want to comment on this from the point of view of political arguments for or against. The CEC must comply with the laws adopted by the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.

The law states that a referendum is considered valid if 50% (+ 1 vote) of the population cast their votes. 226 deputies can lower this threshold or change the wording altogether.

Yes, they can. But if the turnout for the referendum is very low — for example, 10–20% — then the question of its legitimacy may arise. And that is a huge problem.

This immediately brings to mind the story of Yukhym Zvyahilskyy, who became a member of parliament thanks to 1,100–1,200 votes, because his constituency was severely curtailed by the occupation.

This story was also criticised for violating the principle of equality, including by international observers. But we have to admit that the situation was caused by the occupation of part of Ukraine's territory, not by the government's deliberate actions. And the election law said that electoral districts are permanent. At the time, the law didn't say it was impossible to vote in certain areas.

So, we don't need to get rid of the 50%+ rule?

But how can we ensure that more than half of the population turns out to vote in the current circumstances?

Exactly.

But we still don't know what specific question will be put to this referendum. So this is all hypothetical talk for now.

Let's clarify: the question is formulated by an initiative group, and the answer must be "yes" or "no". The initiative group may consist of the president and the staff of a neighbouring condominium association.

According to Davyd Arakhamiya, we publish the peace agreement as it is and ask our citizens whether they support it or not. That's all.

We do not know what the peace agreement will be. If Ukrainians understand that peace depends on it and everyone is satisfied, it could be a mobilising factor: people will come — and it will be more than 50%.

It is impossible to say for sure, because there is too much unknown. Again, what are the conditions: will there be security, will there be no threat of shelling, will people be afraid of mobilisation, how will the issue of voting abroad be resolved? There are many related questions.

At the same time, the results of the referendum are advisory. We remember the 2000 referendum, where all four questions (on dissolving the Verkhovna Rada if deputies failed to form a stable majority within a month; on limiting parliamentary immunity; on reducing the number of MPs from 450 to 300; on transitioning to a bicameral parliament. — S.K.) received between 82.9% and 91.1% support. But they were never implemented into law.

In other words, a lot of time, money and energy was spent on holding the referendum — and, in the end, it was forgotten about. What can be done to prevent this from happening again this time, if, for example, the Ukrainian people do not support the peace agreement?

You understand that this question is not for the Central Election Commission?

Of course. I just want to hear your opinion.

I disagree that the results of the referendum are advisory, because a referendum is a form of direct democracy, when the people make decisions directly. And then the competent authorities have to formalise and implement these decisions. Why they did not implement them in 2000 is a question for them.

How much will it cost the budget to hold the presidential elections and the referendum at the same time and in general?

I cannot say. Again, we are constrained by the legislative framework. Until we know the specific conditions, we cannot calculate. This is greatly influenced by the question of the territory in which the elections will be held, the extent of the destroyed/damaged electoral infrastructure, the method of voting abroad, and a number of other issues for which there are no answers yet.

Are partners generally willing to help with direct subsidies, roughly speaking, specifically for the conduct of elections? Is there any information on this?

This is not a subject of communication between the Central Election Commission and its partners. But our partners are very supportive of us, as the CEC.

"Our proposal: 30 days after the results of the presidential election are announced, the parliamentary process will begin."

Now that we have discussed all of this, let's return to the timing of the electoral process. You have listed so many issues that it is simply unrealistic to deal with them all in the 60 days that may be allotted.

I really hope that parliament will pass a law that is realistic to implement. After all, it seems that everyone understands the importance of these election results being recognised by both Ukrainian society and the world. And a lot of things are connected with legitimacy.

When can parliamentary elections take place after the presidential elections?

Our draft law contains proposals and determines the order of elections: we propose holding the presidential elections first. This is purely for selfish reasons. It is much easier for the Central Election Commission, and the state in general, to organise the presidential election process. This is important given the numerous challenges of post-war elections. In addition, the legislation on presidential elections is much more stable. We assume that there will be far fewer controversial issues requiring legislative regulation before the presidential elections.

As for the elections of people's deputies, we have established a model whereby the parliamentary process begins 30 days after the results of the presidential elections are announced.

But these are only proposals. The sequence of elections is the responsibility of parliament.

And how long will it last?

60 days. We have not proposed any changes to the current deadlines for the parliamentary or presidential election process. On the contrary, we are proposing a rule whereby elections that did not take place due to martial law will be held in accordance with the procedures established by the Electoral Code for the relevant regular elections.

The terms of the CEC members are coming to an end in the autumn. How will completely new people conduct the first post-war parliamentary elections in the country?

In general, this is a question for parliament.

But perhaps everything will be in place before our terms expire.

Do you think it is realistic to expect this to happen by October?

As of now, I do not see any preconditions for elections: the war is ongoing, there is shelling. There are no factual or legislative conditions. However, I do not know how the peace process will unfold. Perhaps they will appear.